"Why can’t we discover that Peter [Parker] is exploring his sexuality? Why can't he be gay?"

With those words, The Amazing Spider-Man star Andrew Garfield has launched a long overdue debate over why virtually every single well-known superhero has remained resolutely heterosexual ever since Superman first appeared wearing a skin-tight costume and bright red briefs.

At least, Garfield should have launched that debate. Instead, the reaction has largely been knee-jerk trolls posting in all caps about a gay agenda, while gay and gay-friendly geeks swoon at Garfield's refreshing attitude.

Meanwhile, the actor's central question — why can't Peter Parker be gay, or at least be, you know, bi-curious? — has gone rather unexplored. Perhaps it's because at first glance, the question seems intractably depressing to answer, inviting the kind of cynical "because mainstream America would reject a gay Spider-Man" shrug that makes you hate people in general for sucking so much. Or, conversely, the question seems so rhetorical — "Because of course he should be!" — that trying to answer it feels maybe a little dumb.

But as Mark Harris pointed out in his terrific essay for Entertainment Weekly, in the last 10 years, on the big screen and on the page, Spider-Man has died, sung, turned evil, and been recast as a half-black, half-Latino teenager. And then there was the time Peter Parker made a deal with the evil Mephisto to save the life of his elderly Aunt May by erasing the entire existence of his marriage to Mary Jane Watson.

So, truly, if all that can happen — or if Wolverine can kill an alternative universe version of himself, or two different Supergirls can merge to become an "Earth-born angel" — why is it so difficult to allow these characters to explore their sexuality more forthrightly?

The answer, it seems, may lie with comic books themselves.

"I think it has a lot to do with the cyclical nature of the big-name comics industry," says Charles "Zan" Christensen, founding president of PRISM Comics, a nonprofit organization that serves as a kind of clearinghouse for LGBT comics and comic book writers. "Even if something very radically different happens, regardless of what it is — marriage, children, death — nothing lasts forever."

Indeed, those aforementioned storylines for Spider-Man, Wolverine, and Supergirl that pulled the character away from their established core identities were all eventually retconned out of existence — or likely will be soon. "Everything always gets reverted to what it was and then its relaunched as a brand new thing," Christensen says. If a writer were to launch a story arc that made Spider-Man, Batman, or Wonder Woman gay, they would inevitably become straight again — it's just the way comics work. But "de-gaying" an iconic superhero could be just as problematic as "gaying" that superhero in the first place.

"You're dealing with a community of queer characters in comics that is so small to begin with," Christensen says. "All those characters are bearing a burden of representation that is inordinately high compared to their stature in that universe. They have to stay the way they are and grow in number, otherwise it's a step backward, because they're already so underrepresented. ... You whittle away at it, people are bound to take offense. That's just kind of where we are right now." (A rep for Marvel declined to comment for this story, and a rep for DC did not respond to a request for comment.)

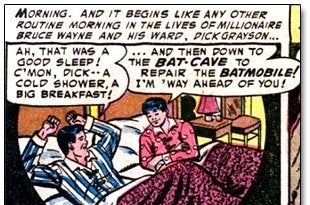

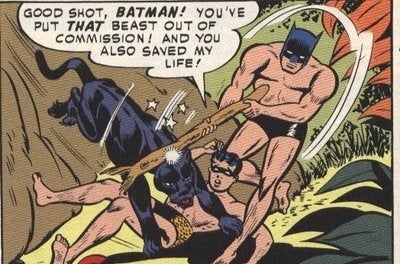

What makes the lack of major gay superheroes even stranger is how gay comic book heroes otherwise are: all that tight spandex clinging to all those idealized bodies spending all that time and energy hiding a "secret identity." Batman and Robin's relationship became so unmistakably homoerotic that Batwoman was introduced to prove the Caped Crusader's hetero bona fides. And from the start, the X-Men have been stand-ins for virtually every marginalized minority. Yet with all this gay subtext rampant within comic books, for decades, no characters at all were allowed to actually be gay.

And that's the world of comic books. Comic book movies are stuck within an even more rigid set of expectations for a famous superhero's established biography. The Amazing Spider-Man director Marc Webb chuckles good naturedly when asked about his star's comments about Peter Parker's sexuality. "I don't think you'll find anybody more supportive of the LGBT community," he says, "but when it comes to his sexuality, I think we're going to stick to the comics.…I am working for a character that is much bigger than me, whose experience has to be universal in some way, and has to be mythological in a way that transcends personal experience, if that makes sense. I have obligations to a canon and to a character that pre-date my birth."

From Webb's perspective, making a character gay who was heretofore straight wouldn't be very effective anyway. "It's not something that you toy around with, that you slap on later," he says. "I think it's something that's fundamental to who people are." Instead, says Webb, "You could create a character where [being gay] was fundamental to his life and his understanding of the world."

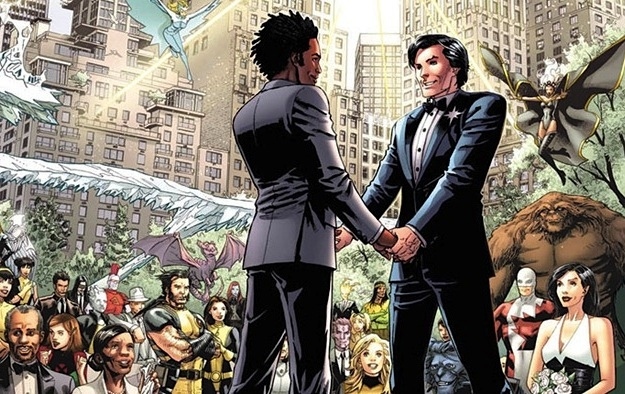

Over the last 15 years, that very thing has been happening, with the birth of permanently gay superheros like Northstar, Midnighter, and Apollo. But unless you're a regular comic book reader, you've likely never heard of them — they simply don't hold the same cultural power as Spidey, Batman, Wolverine, or, say, Green Lantern.

Ah, yes! Green Lantern! Last year, to great fanfare, DC Comics made Green Lantern gay — well, it made the Alan Scott Golden Age version of the character who lives in an alternative universe called Earth 2 gay, but still! Similarly, after largely disappearing from comics for 25 years, DC resurrected Batwoman as a lesbian in 2006. (The irony was likely not lost on her.) Over at Marvel, the subtext between X-Factor mainstay Rictor and his alien BFF Shatterstar became overt text when they locked lips... and came out as a same-sex couple in Peter David's run. And this is where Christensen sees a real opportunity for growth with LGBT comic book characters. "I find that it's the characters that have lost popularity and that are ripe to be harvested for something brand new," he says. "[They] don't have much of a following or any ties to the past that are important anymore."

Besides, Christensen notes that talk of "gay" or "straight" superheroes ignores the first part of Garfield's question: Why can't Spider-Man just explore an attraction to men? "The future of representation of queerness in general, it might not be about identity at all," he says. "A character has a relationship with a woman one year and then discovers he likes men the next year. It doesn't have to change who they are. They may be confused. They may not be confused. They may want something and they're not quite sure why they want it. And that doesn't have to mean that that character is no longer for straight men or no longer for women or no longer for gay men. I would love to see that."

Before you scoff at the idea of Bruce Wayne and Clark Kent giving each other a once over in director Zack Snyder's recently announced movie featuring Batman and Superman, consider James Bond. There has been no more steadfastly heterosexual character in modern popular culture than Agent 007, and yet last year, in Skyfall, Bond did the heretofore unthinkable: He more than hinted that he'd fucked around with guys. Sure, he was reacting to the slithery flirtation of the flamboyant villain Silva (Javier Bardem), but it was a deliciously inclusive moment, not a gay panic-y one. And with it, Skyfall grossed over $1 billion worldwide. If Bond can get a little gay, why not Peter Parker?

Meanwhile, perhaps the biggest LGBT addition to the world of comic books has had nothing to do with superheroes: In 2010, the Archie comics introduced Kevin Keller. He's since earned his own set of issues, and earlier this year, the issue of Life with Archie about Kevin's wedding sold out.

"Who would have thought that we would have a gay Green Lantern, a gay high-profile Batman family character — Batwoman — and then a gay character in Riverdale of all places?" Christensen says. "These are things that I never would have imagined when PRISM started 10 years ago. Things change pretty quickly. I think that once [comic book] companies realize others companies are doing it and having success with it and making money from it, they'll start to try it." Or, perhaps, explore it.