This week, new posters for Transformers: Age of Extinction started appearing in major cities, but instead of selling the Michael Bay movie outright, they appeared as if they were anti-Transformer propaganda.

To do that, the campaign evokes the kind of imagery and language that historically has been used in propaganda designed to intimidate undesirables, or PSAs meant to raise awareness of terrorist attacks.

Transformers: Age of Extinction, which opens June 27, is far from the first major studio film to use this kind of quasi-propaganda campaign. Over the past five years, in fact, it has become an increasingly common tactic of studio marketing teams, especially to sell original films with a (relatively) complex central premise.

And one of the strangest common threads through many of these campaigns is that they are essentially asserting a negative idea that the film itself will actively refute. (For example: The Autobots are just trying to help, you nimrods.)

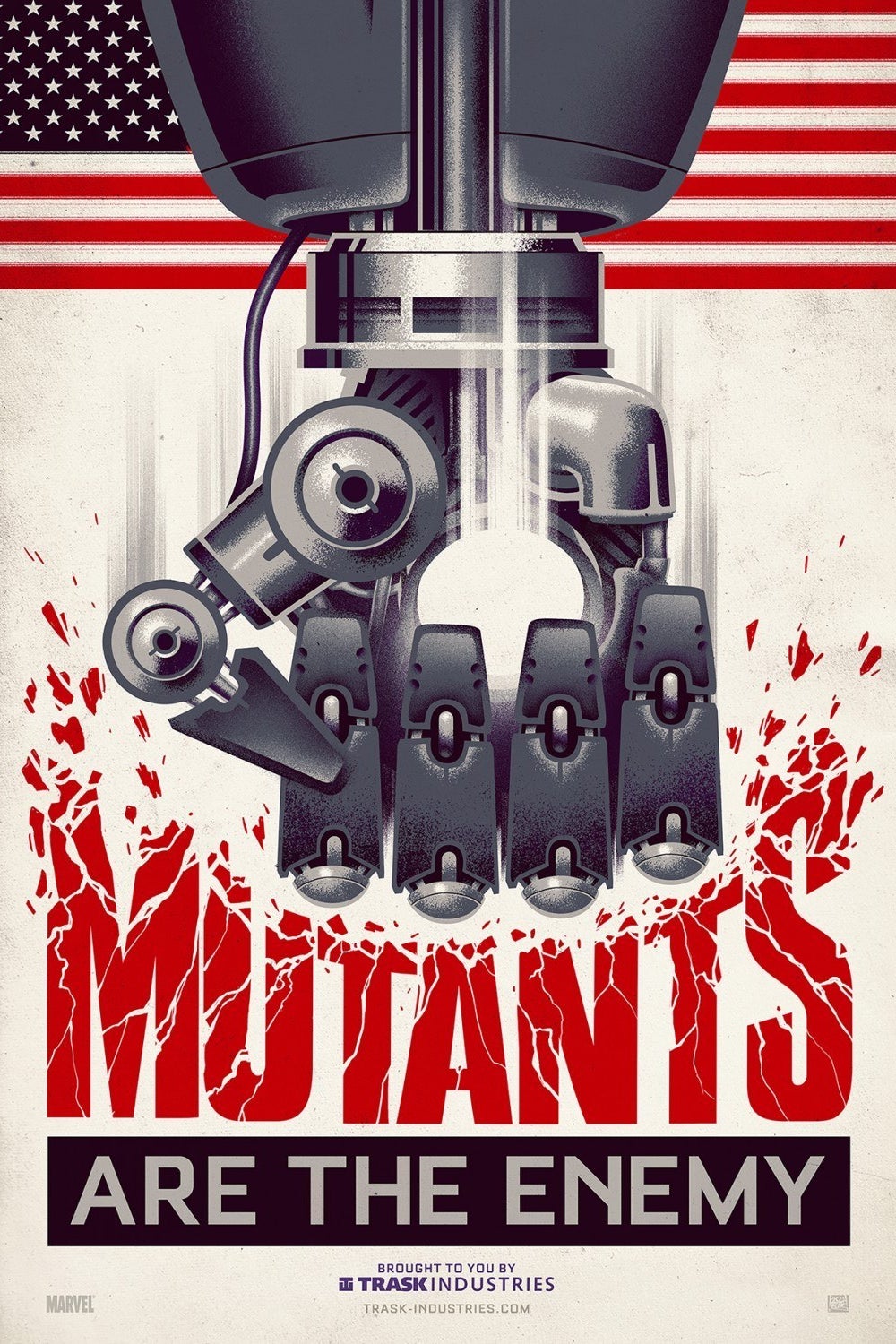

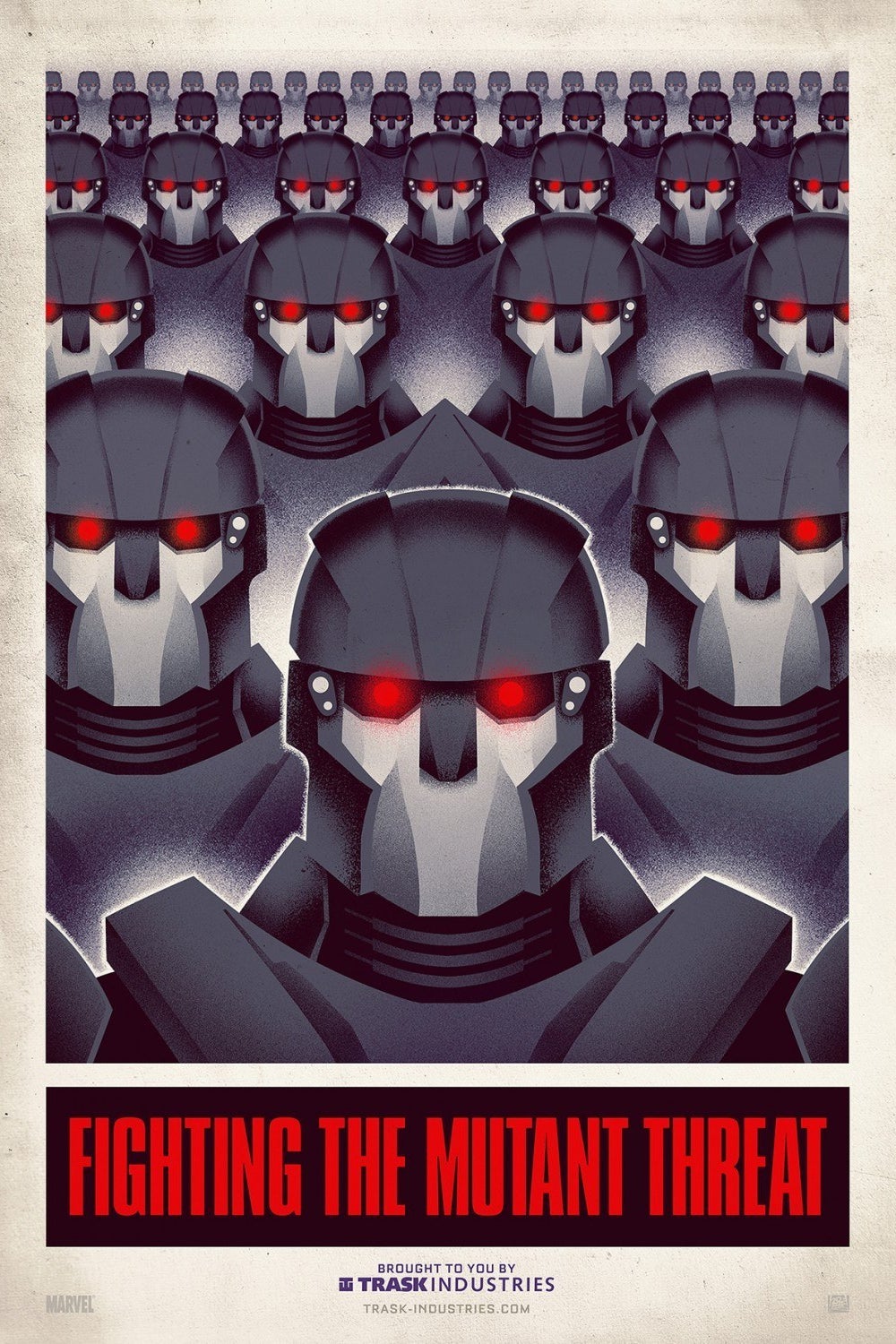

At the 2013 San Diego Comic-Con, X-Men fans were first introduced to the franchise's latest installment, Days of Future Past, with two posters that presented the mutant-hunting Sentinels as if they were stars of anti-mutant propaganda.

Again, the core idea being sold here — mutants bad! crush them! — is directly at odds with the film itself. But save for subtle corporate logos in the bottom corners, there is no obvious hint that either poster is meant to promote a movie at all, let alone Days of Future Past. Of course, in-the-know fans would have figured it out almost immediately. By flattering fans' knowledge of the X-Men comics while presenting the marketing as if it were part of the world in which those fans really live – even in a somewhat tongue-in-cheek fashion — these posters aim to make fans feel in some small way like they are more "inside" the movie. And therefore more likely to go see it on opening weekend.

In the case of Days of Future Past, they did, in droves.

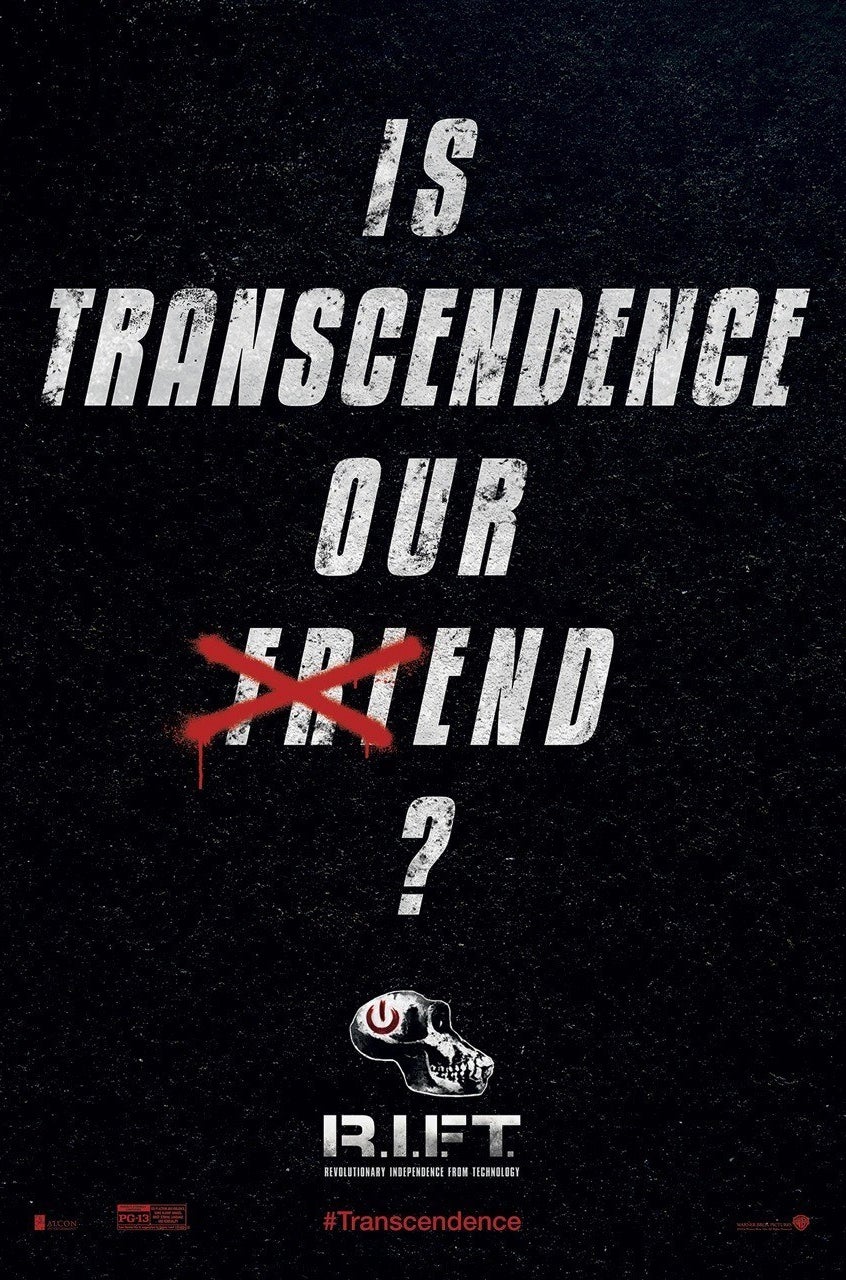

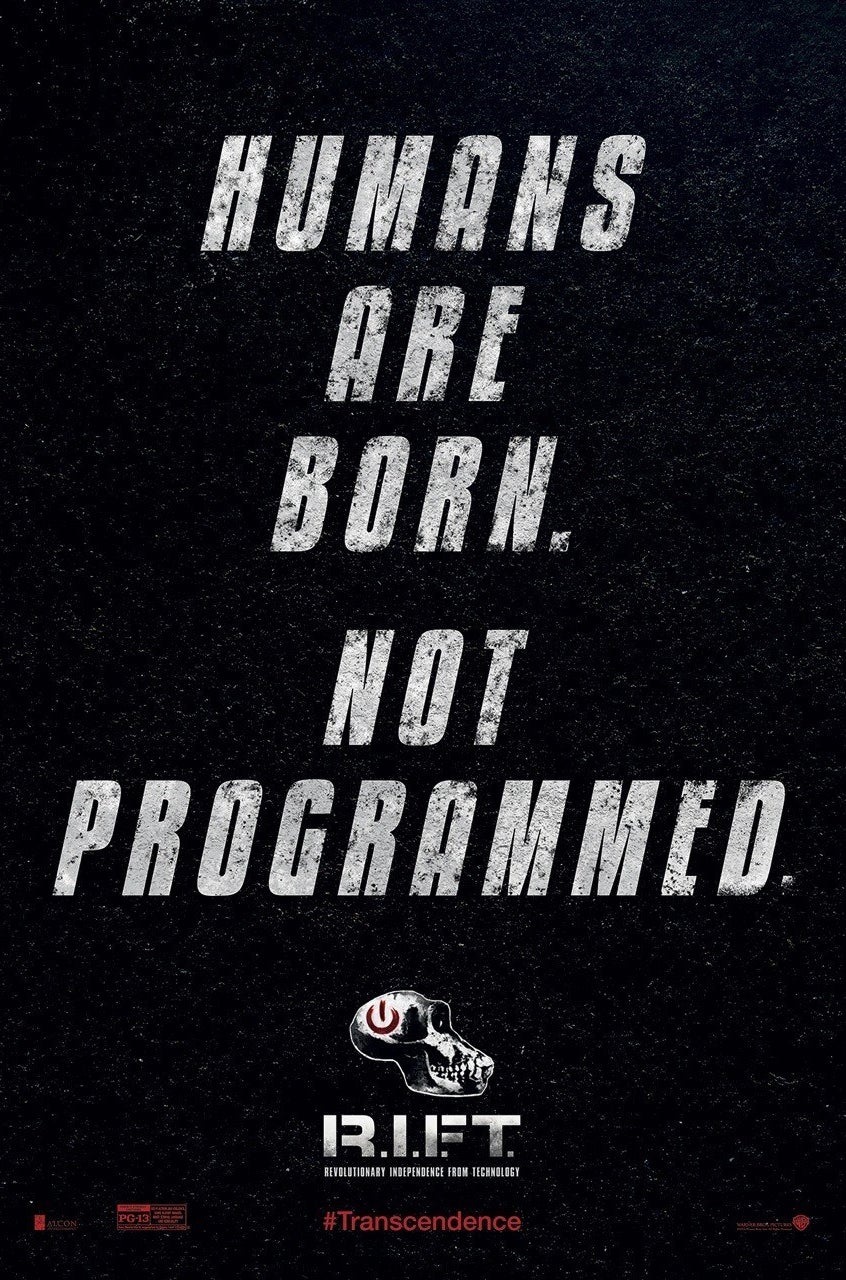

But in the case of the Johnny Depp sci-fi thriller Transcendence — which was sold in part with posters seemingly from the film's anti-technology antagonist R.I.F.T. — audiences largely stayed away. The film has grossed just $22.8 million in the U.S. since it opened on April 18.

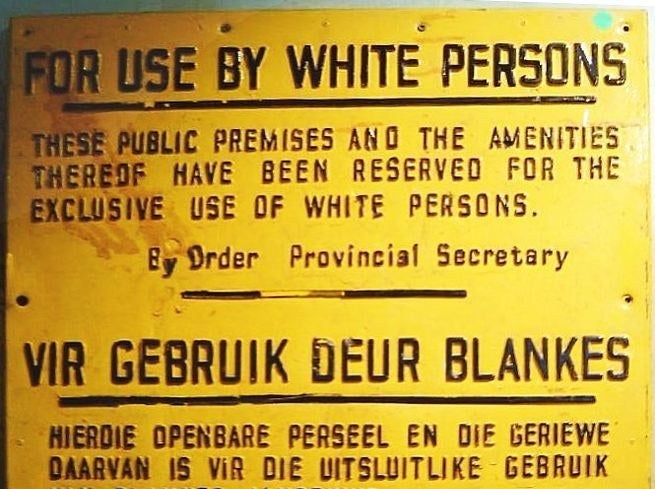

The current trend of propaganda-as-movie-marketing was ignited by 2009's District 9. The film, about a race of aliens stranded in segregated squalor in the middle of modern-day Johannesburg, explicitly evoked South African apartheid. And so did the film's ad campaign.

People actually called the toll-free number, and actually "reported" seeing a non-human.

The District 9 campaign was unusually far reaching, including ads on buildings, bus-stop benches, and buses themselves, forbidding the presence of "non-humans."

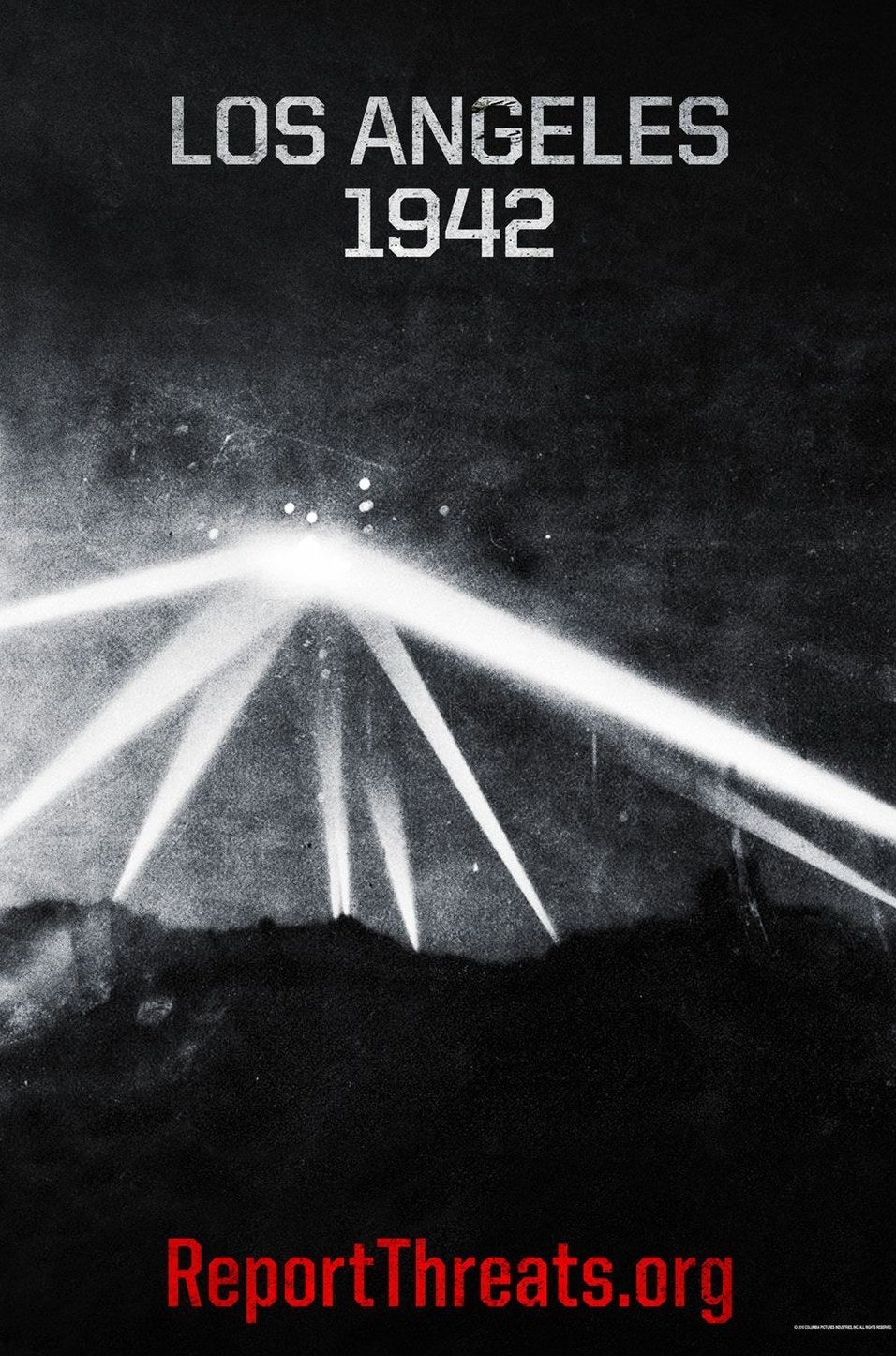

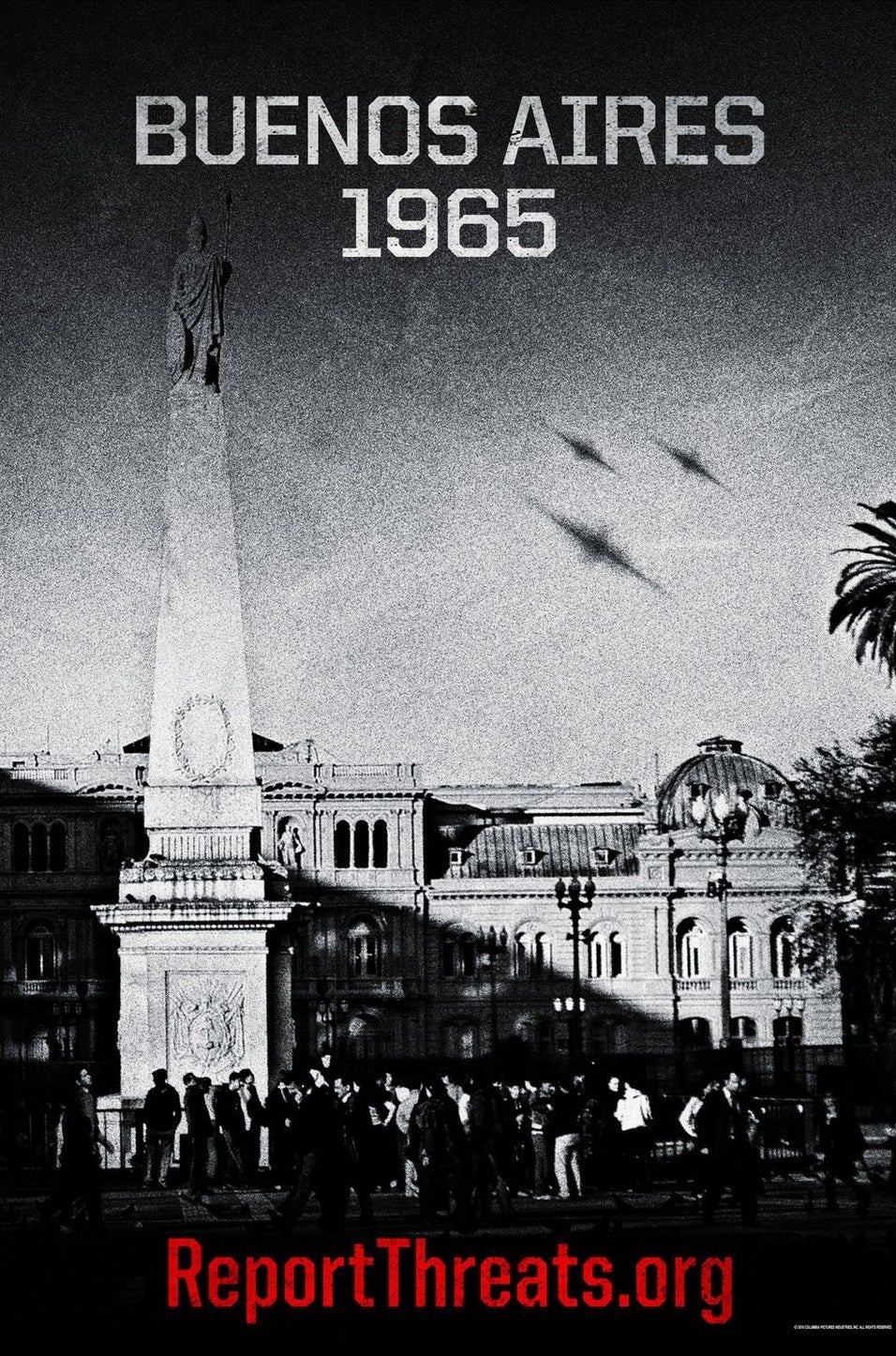

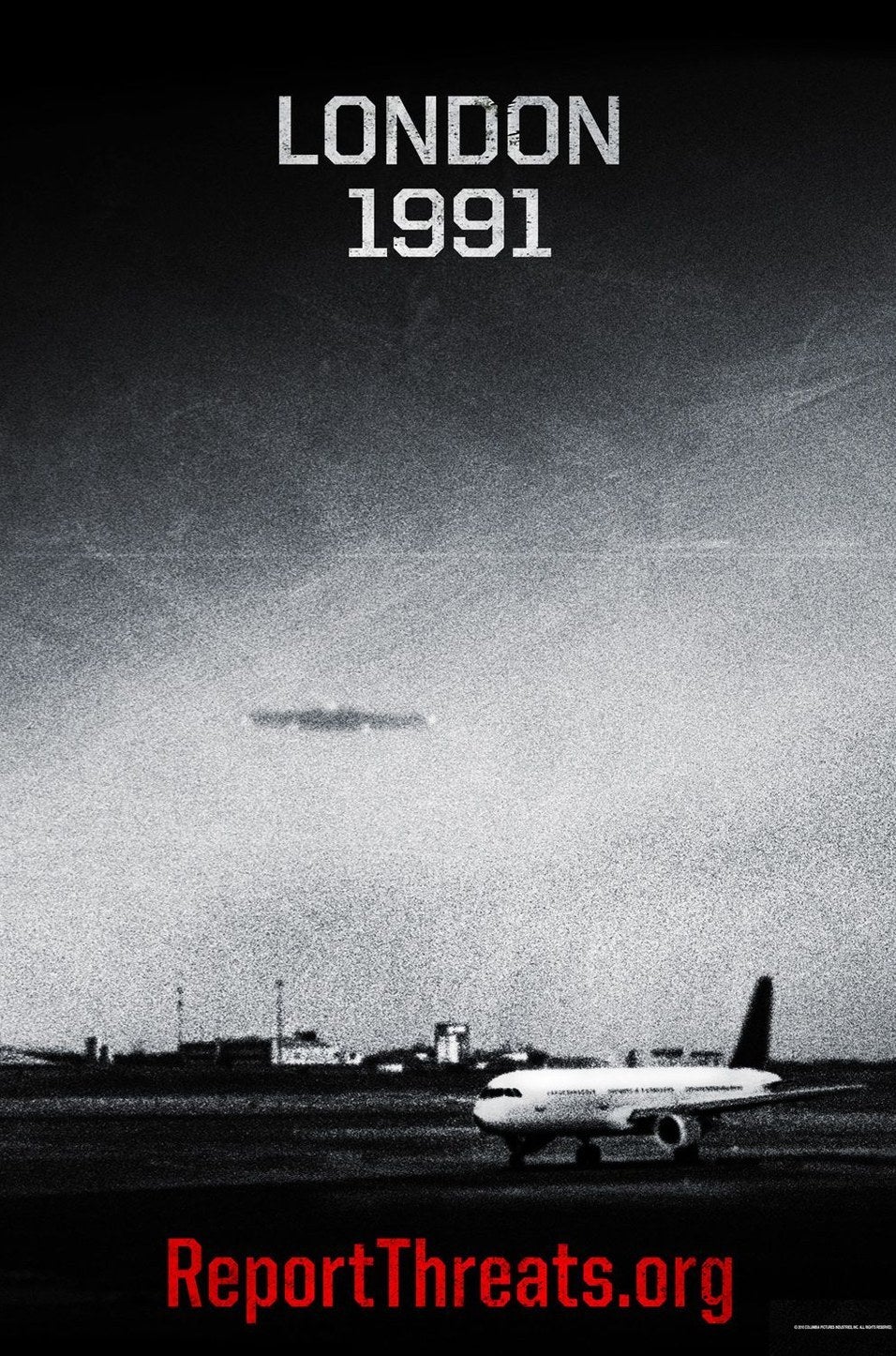

Since then, a handful of movies have adopted variations on this style of marketing. They include 2011's Battle: Los Angeles…

Domestic box office: $83.6 million.

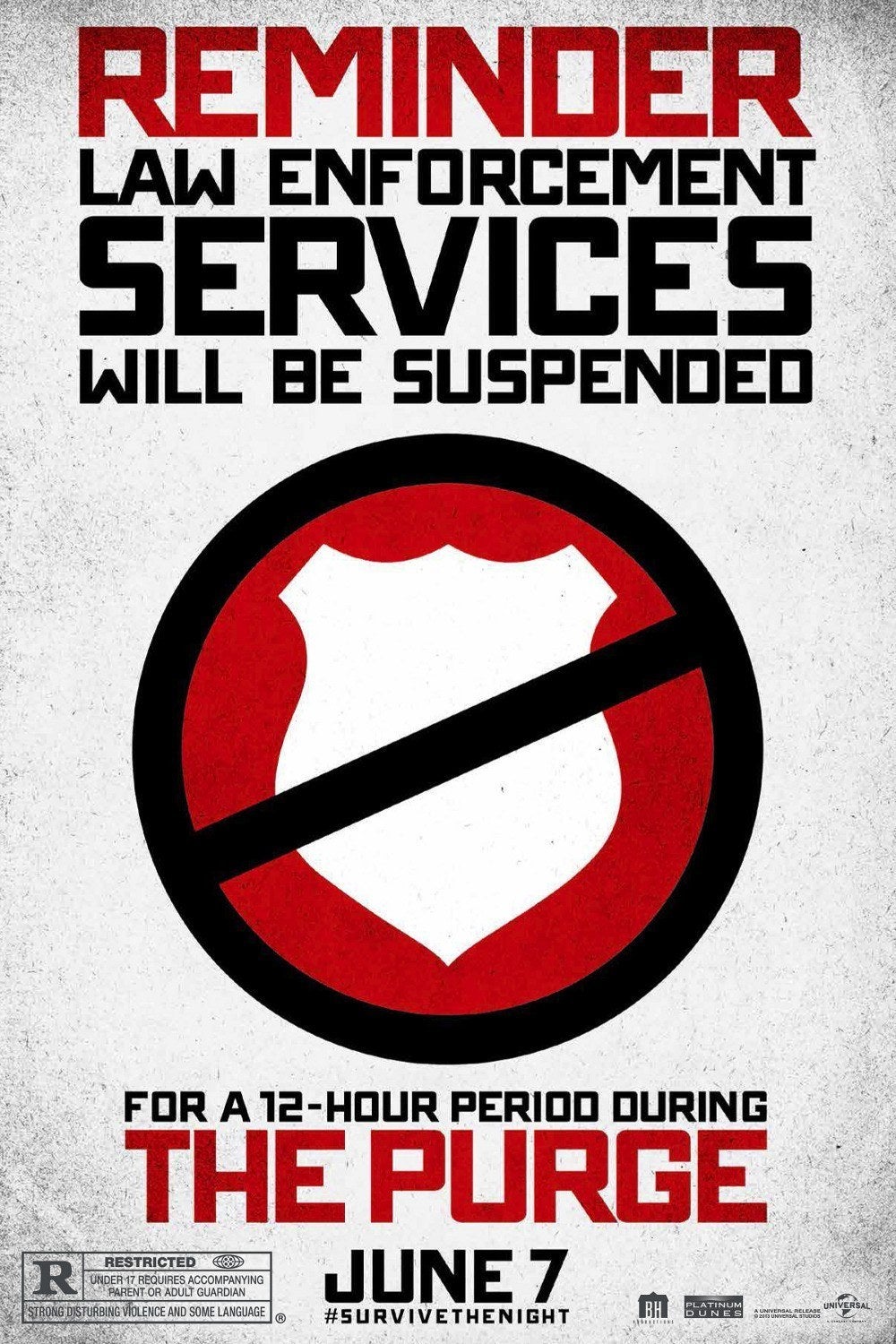

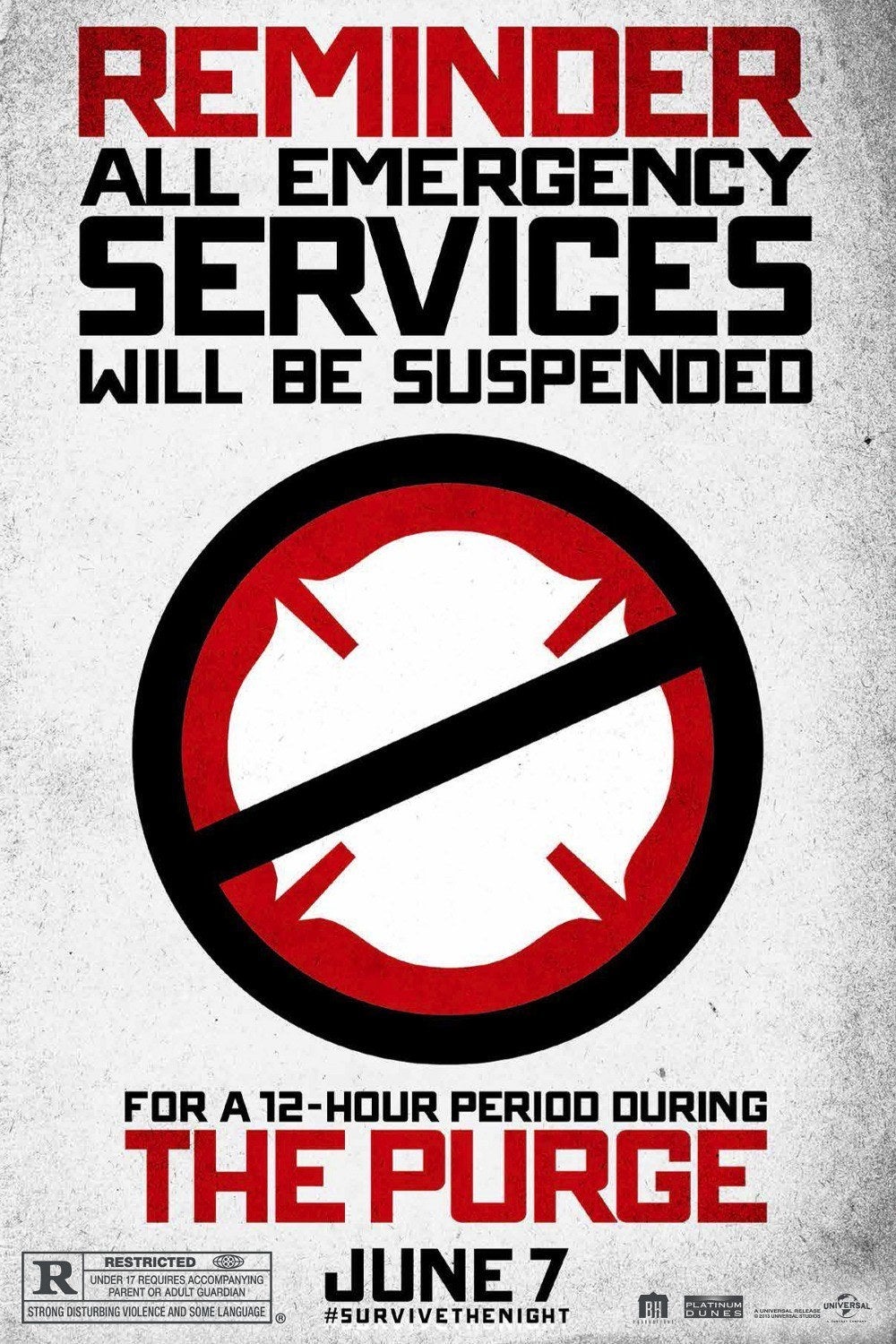

2013's The Purge…

Domestic box office: $64.5 million

And 2013's Ender's Game.

Domestic box office: $61.7 million.

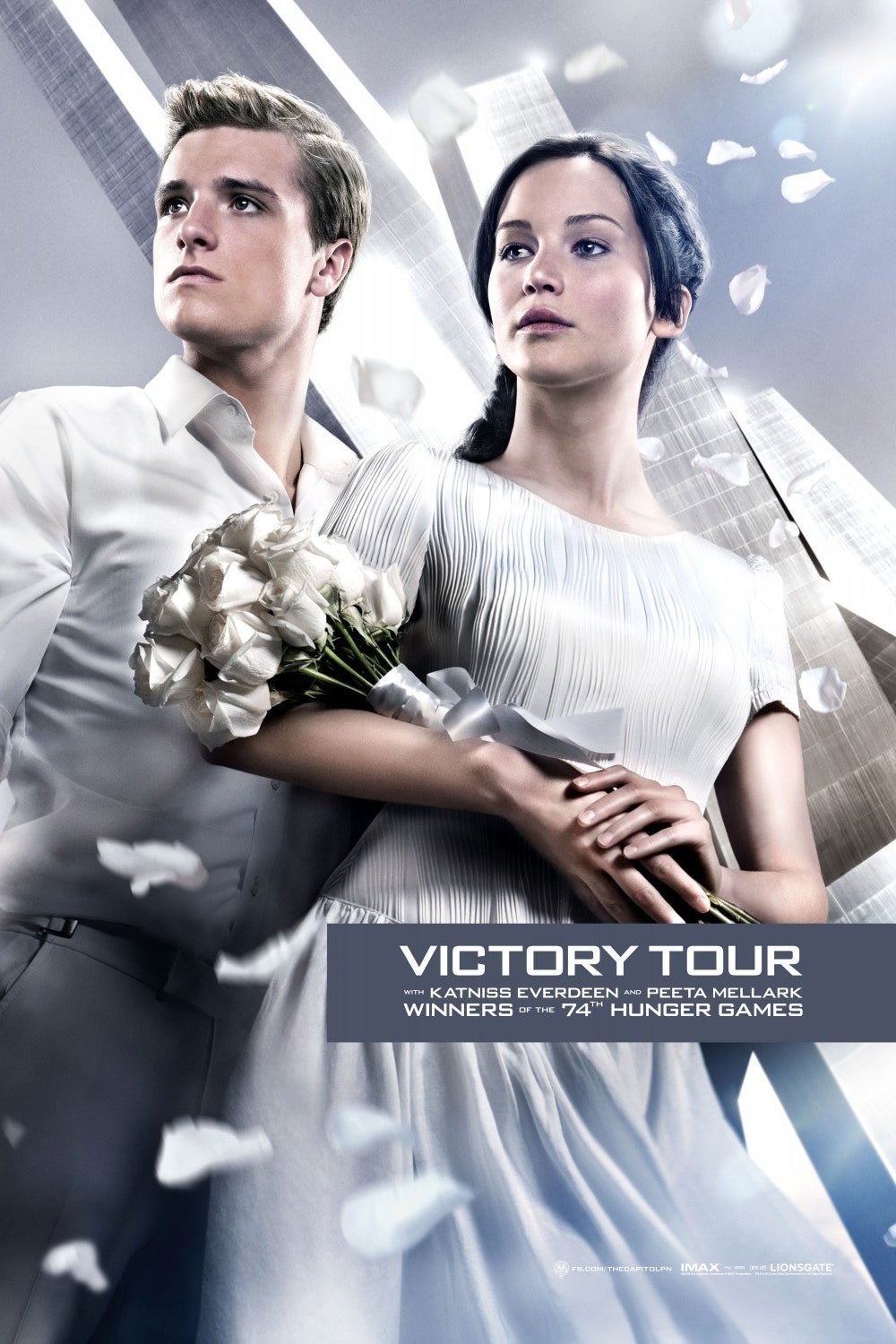

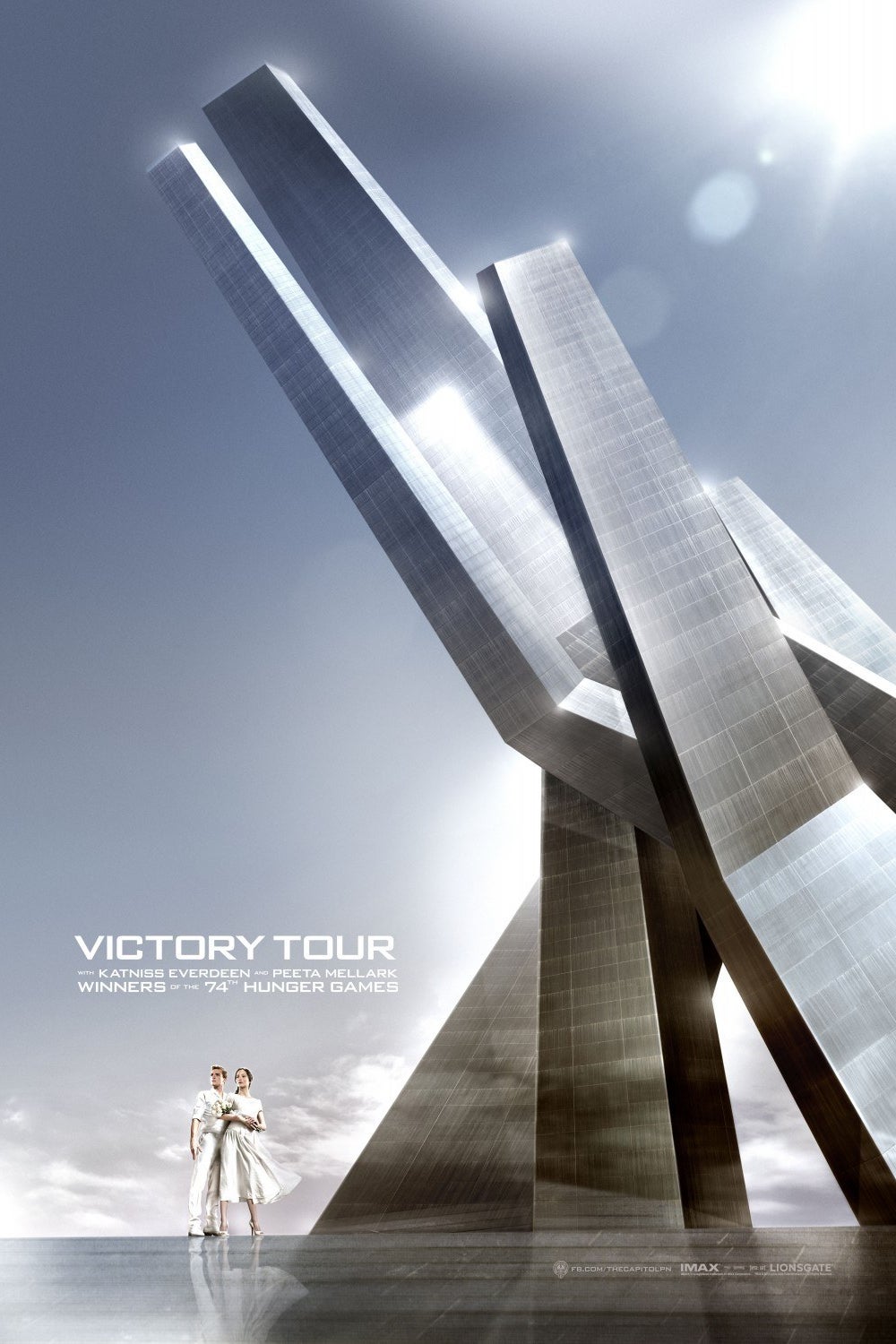

Other films have used propaganda-style marketing as just one part of a much larger campaign, like these teaser posters for The Hunger Games: Catching Fire.

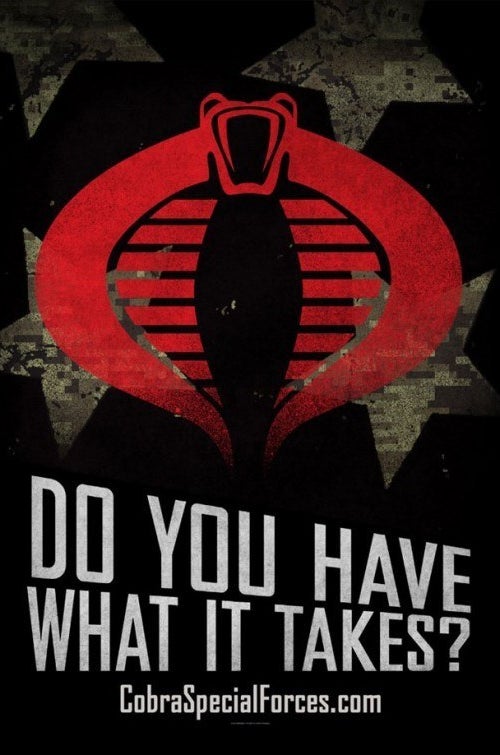

Or these posters for Total Recall (2012), G.I. Joe: Retaliation (2013), and Pacific Rim (2013).

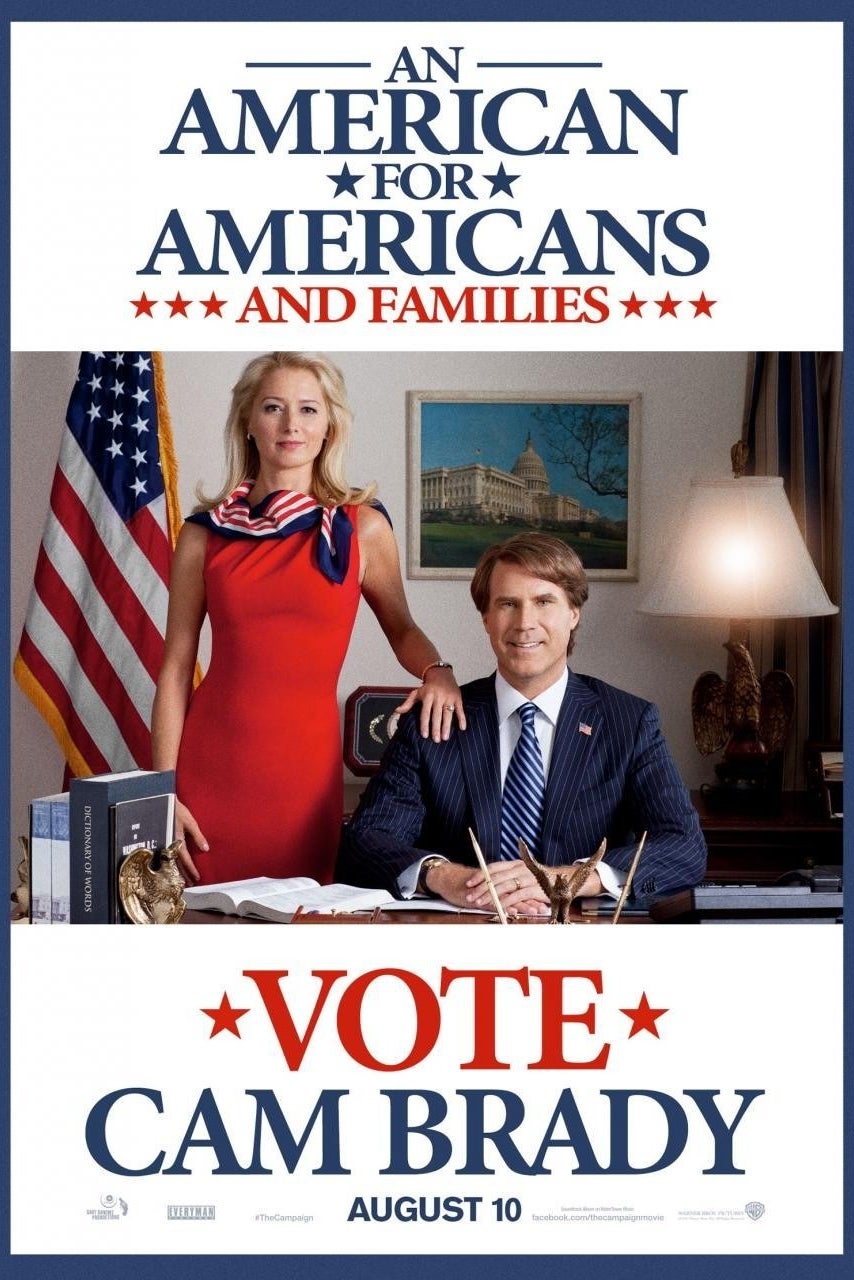

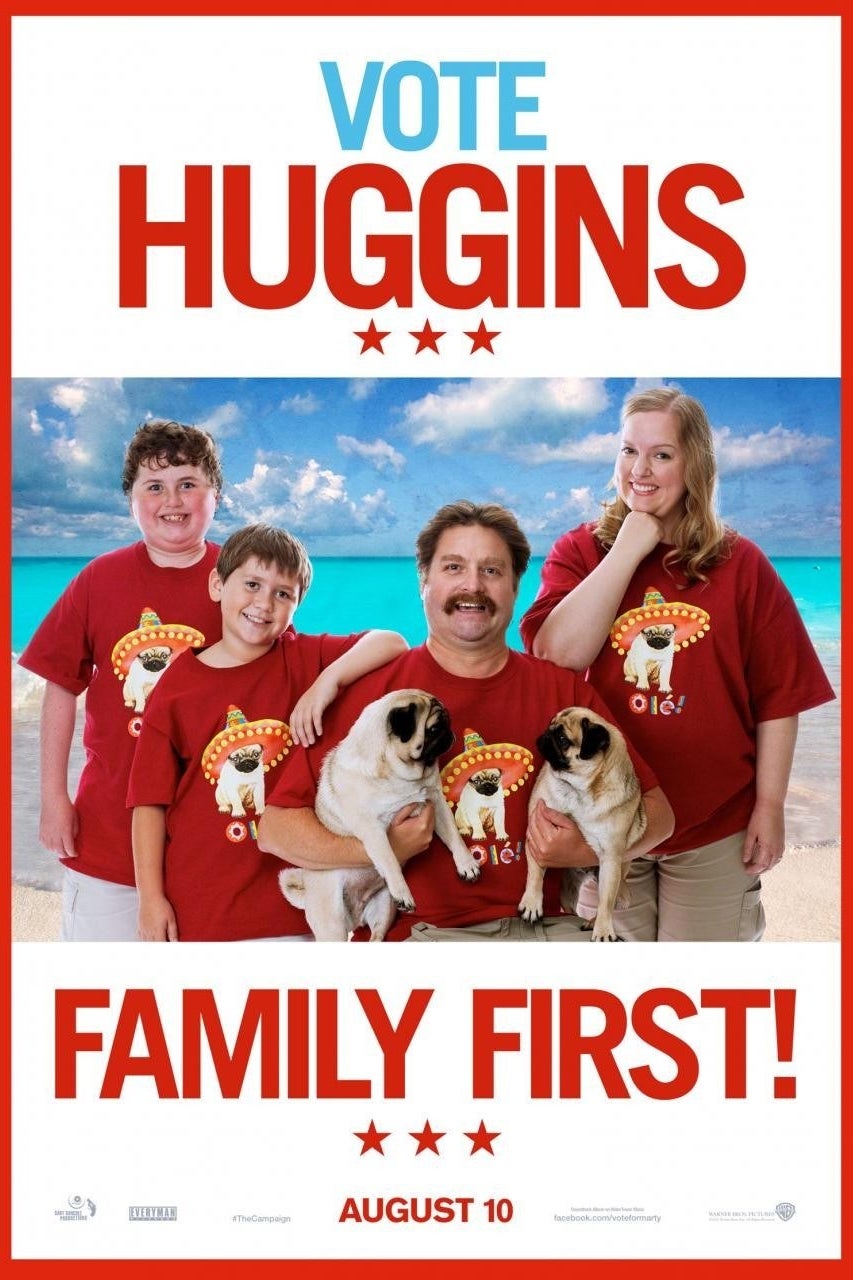

While a propaganda campaign is usually restricted to high concept sci-fi thrillers, it has, on at least one recent occasion, been deployed for a comedy, 2012's The Campaign.

To be sure, propaganda is such a well-worn trope of the last 100 years that any movie marketing campaign that employs it risks falling into self-parody — like these unauthorized (but very funny) The Hunger Games posters from College Humor.

There's another more dangerous risk too: co-opting language and imagery first employed by governments to enforce policies of segregation.

When a film is explicitly referencing those policies, like District 9, such a campaign can ultimately help to reinforce the movie's themes. But when the film is ultimately meant to be a $200 million summer thrill ride, the above painful images are likely not the ones a studio would most want to evoke.