The last call Oregon rancher Dwight Hammond Jr. made before heading to federal prison on two counts of arson in 2016 was to a man he hardly knew. Forrest Lucas, who made his fortune on oil engine additives, promised Hammond that he would do whatever he could to get him and his son, Steven, out of prison.

Early Tuesday morning aboard Air Force One, en route to the NATO summit, President Donald Trump signed an official clemency order pardoning the two men. Lucas — a 76-year-old Indiana self-made millionaire with tight ties to the Trump administration — had fulfilled his pledge.

For nearly two decades, the Hammonds had been engaged in skirmishes with the Bureau of Land Management, an agency that functions as a go-between for ranchers and the federal land they lease for grazing. They pushed back, often threateningly, on regulations regarding the Malheur Wildlife Refuge, which bordered the Hammonds’ grazing allotment, and they set unpermitted fires on BLM land. After a second fire in 2006, the pair were charged with 19 different crimes, but eventually arranged a plea deal for just two charges of arson on federal land, which carried a minimum of a five-year sentence. The judge declared that such lengthy jail time qualified as cruel and unusual punishment, instead sentencing Dwight to three months and Steven to one year and one day. The pair served their time and returned home. But the federal government successfully appealed the sentence, and on Jan. 4, 2016, the Hammonds were ordered to return to prison.

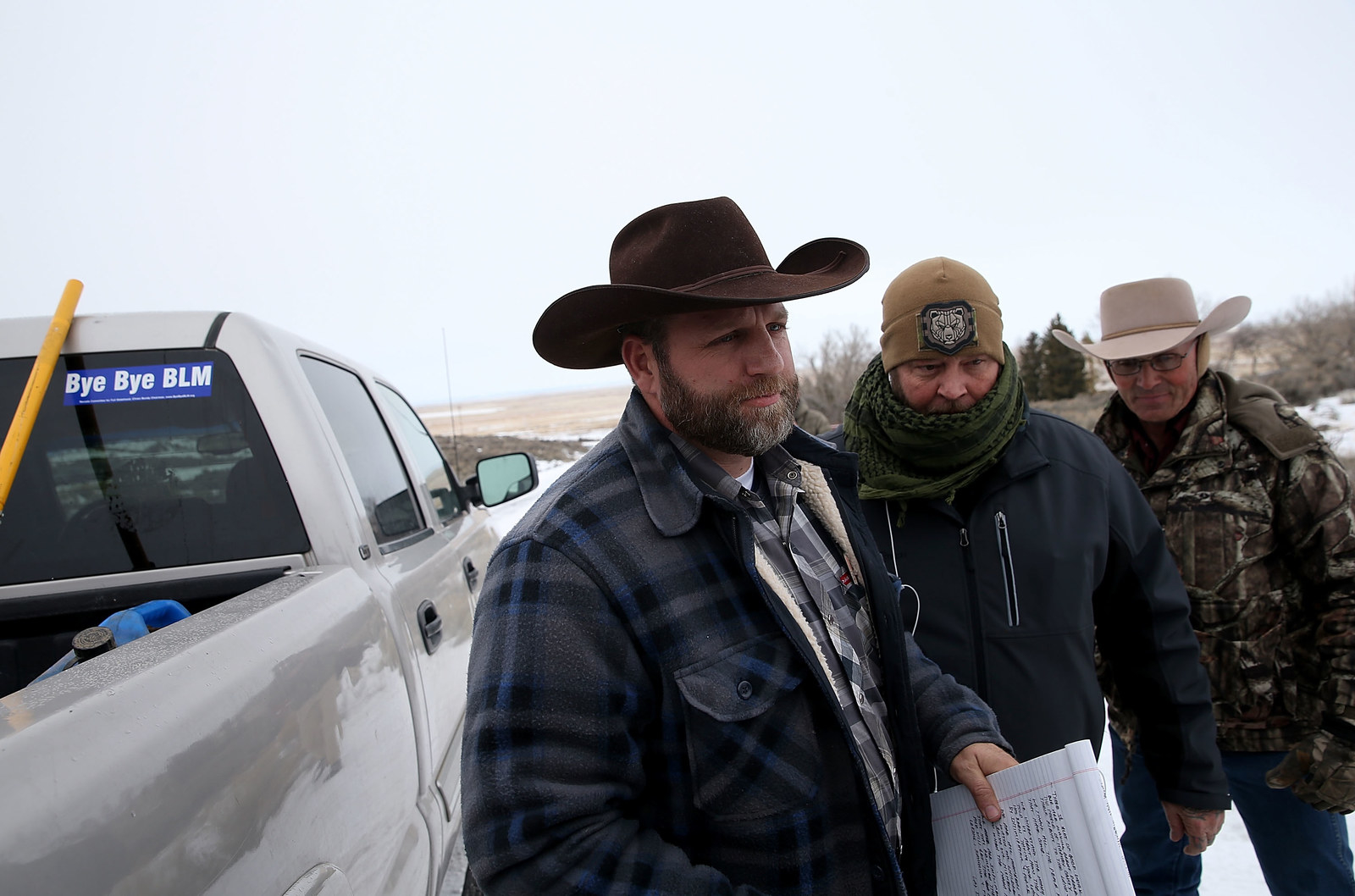

The verdict brought Ammon and Ryan Bundy — who, along with their father, Cliven, had been involved in an armed confrontation with BLM officials over the management of their grazing allotment in Nevada — to Eastern Oregon. On Jan. 2, Ammon led several hundred people on a peaceful march through Burns, Oregon, in support of the Hammonds. At the end of the march, he made a declaration: Whoever wanted to take a “hard stand” against the government should follow him — thus launching what would become the 41-day armed standoff at the Malheur Wildlife Refuge.

The Hammonds, however, weren’t there. Nor did they condone what the Bundys and others had done in their name. When the occupation began, they were back on their ranch with Dave Duquette, Lucas’s close associate. When the Hammonds flew back to a hero’s welcome in Burns, Oregon, it was aboard Lucas’s private jet. Lucas, whose company, Lucas Oil, currently holds naming rights for the Indianapolis Colts’ stadium, has made a pro-agriculture, anti-regulation agenda his mission over the past eight years — and had decided that the Hammonds fit into his larger master plan.

To achieve his goals, Lucas has used a nonprofit he founded, Protect the Harvest — devoted to “working to protect your right to hunt, fish, farm, eat meat, and own pets” — as well as his close ties to Vice President Mike Pence, Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke, and Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue, whose top adviser is a former employee of Lucas’s. As Duquette puts it, “the access is very good.”

“Most people wouldn’t get involved,” Duquette told BuzzFeed News in early June. “But thank god for Forrest Lucas, because he’s been willing to take on the hard issues.” Among those hard issues: fighting environmental activists, pushing back against regulation, and protecting farmers and ranchers from what they see as federal overreach. That’s why Lucas grew interested in the Hammonds in the first place. “We’re all about affordable food and land use and personal rights,” Duquette explained. The Hammond case “intersects perfectly with the Protect the Harvest mission.”

Protect the Harvest has built a positive rapport with the ag community by sponsoring scholarships and racetracks and film festivals. But the nonprofit has also benefited by inflaming the community’s anxieties that a time-honored way of life is coming to an end — while eliding the fact that its own lobbying on behalf of corporations and against regulations has hastened the destruction of that lifestyle.

For those active in the agricultural world, Lucas has primarily been known for his strong stance on animal regulation, actively opposing attempts to limit or monitor mistreatment of pets and livestock with laws that would, for example, establish minimum spacing for hen cages or veal calf pens, crack down on puppy mills, or prevent intentional mutilation of Tennessee walking horses. A particular target of his efforts has been the Humane Society of the United States — the national organization that has spearheaded the vast majority of initiatives related to animal regulation, and which Lucas has referred to as “terrorists.”

But Lucas’s agenda is hardly limited to cage sizes and puppy mills, as reflected by his support of the Hammonds and, by extension, the Bundys and others opposed to federal control of public lands. And to get what he wants, Lucas has employed a highly sophisticated lobbying and messaging machine, which does everything from funding opposition to municipal spaying and neutering ordinances to orchestrating “range rights” conferences, streamed live on Facebook to an audience of thousands.

Protect the Harvest has spent millions producing web videos and memes that spread across the dozens of Bundy-adjacent Facebook pages that have popped up in the last decade. It also focuses on messaging to children: There are anti-regulatory Protect the Harvest coloring activity sheets, and a pro-ag Protect the Harvest–branded teaching curriculum available for download on their website. In 2015, Lucas began producing feature-length films — starring Hollywood actors like Sharon Stone, Jon Voight, and Jane Seymour — to promote his strongly anti-regulation agenda.

In 2015, Lucas began producing feature-length films — starring Hollywood actors like Sharon Stone, Jon Voight, and Jane Seymour — to promote his strongly anti-regulation agenda.

Lucas’s film and television production studio, the Corona, California–based ESX Entertainment, currently has five films in production — including Stand at Paxton County described as the story of a rancher and his daughter who “face off against state and local authorities who by questionable means relieve local ranchers of their livestock and way of life.”

After Trump took office, Lucas made the short list of potential appointees for interior secretary. Although Montana Rep. Ryan Zinke ultimately got the job, he has provided an open door to both Lucas and Protect the Harvest. Meanwhile, Brian Klippenstein, who is still listed as PTH’s executive director, now works as senior adviser to Perdue. Pence’s vice presidency has been a boon for Lucas, who, according to a Protect the Harvest spokesperson, has been friends with Pence since before he took the office of Indiana governor.

In addition to Lucas’s own role as one of Trump’s agricultural advisers, public records indicate that Lucas met with Zinke in April 2017 to discuss wild horses, grazing access issues, and national monument designations. In October, when Pence flew to attend an Indianapolis Colts game, abruptly leaving when players knelt during the national anthem, he first spent time posing for photos with Lucas and Duquette. Protect the Harvest also has ties to former EPA chief Scott Pruitt, who was a featured speaker at a Protect the Harvest event in Indianapolis on Jan. 26, 2016.

Lucas, the Hammonds, and Duquette on Lucas's private plane back to Burns.

Lucas’s investment in the Hammonds — and the Bundys, who’ve been invited to Protect the Harvest–sponsored forums — is a means to an end. They have become symbols of the way many rural Americans feel they’ve been wronged by federal overreach, and Lucas, much like Trump, leverages those feelings to build support for one of his overriding goals: wide-scale deregulation of big business.

This is the story of how Forrest Lucas became the behind-the-scenes architect of a multipronged political and propaganda machine — unknown to most Americans, yet with an outsize influence on the current administration and the way millions think of their rural way of life, the industries that shape it, and the government’s role within it.

“This administration has been pretty good at asking for problems,” Duquette explained. “And then addressing them.” The Hammond pardon is the first such Protect the Harvest “problem” that’s been directly addressed on the national stage. But with Lucas’s direct access to multiple wings of the administration, it’s unlikely to be the last.

Lucas, Duquette, and Ramona Hage Morrison at the Department of the Interior.

To understand why an incredibly wealthy man like Lucas would care about the fate of a pair of Oregon ranchers, you have to consider the concept of “the harvest” as Lucas is using it: a stand-in for everything from actual crop yields to what he views as the fundamental right to make a living as one sees fit off the land. In tax filings, Protect the Harvest describes its mission as educational: “to ensure accurate information is communicated to the general public with the rise of various groups threatening to end modern agriculture and hunting in the United States.”

In practice, this “accurate information” has centered on a cluster of issues that are closely tied to Big Ag’s priorities: portraying animal rights activists and environmentalists as out-of-touch liberals bent on ending the rural way of life; characterizing regulation and federal oversight, particularly on public lands, as a means of curtailing American liberty; and advocating for and providing platforms for public figures — such as the Hammonds — to function as symbols of widespread persecution of the ag community.

That this apparatus was built in just eight years, by a man with little in the way of a visible political profile, is a testament to what a few million dollars can do in our current American ideological landscape. And while Lucas may seem like an unlikely political figure, his “all-American” rise, and the obstacles that defined it, go a long way toward explaining the ardor and anger fueling his cause.

While Lucas may seem like an unlikely political figure, his “all-American” rise goes a long way toward explaining the ardor and anger fueling his cause.

At age 76, Lucas has deep brown hair that seems to belie the natural aging process. When he speaks with the press, he tends to wear shirts emblazoned with the Lucas Oil logo of his company, or a race car jersey. He’s the sort of man who’d commission a documentary about his own life — titled American Real: The Forrest Lucas Story — show it at a film festival, and then make it nearly impossible for anyone to view it again. He considers himself an embodiment of the American dream: a boy who, as he tells it, grew up without electricity in rural Indiana but then, over decades of hard work and fair dealings, scraped his way to a multimillion-dollar company.

Born in 1942, Lucas grew up on a farm in Elkinsville, Indiana — living, as he put it, “pretty much like people lived in the 1800s.” “Most people now could only read about that,” he said, “but I got to see the tail end of it. Most people think it’s kind bucolic, but it’s actually a pretty hard way to go.” According to Lucas, when he was 9 years old, he got his start as an entrepreneur by going door-to-door, barefooted, selling a supposed miracle cure called Cloverine Salve.

Lucas was, in many ways, a typical farm kid. He’d wake in the morning to take care of the cows and pigs, go to school, and return home to care for them again. At age 15, he left home to work at a cattle ranch in Harrison County, near the Kentucky state line. He graduated high school, then, as he later put it, “went to a long college called hard knocks.” By age 18, Lucas was a married man with a child — and left the ranching life to make a living for his family, hauling dirt, finding odd construction jobs, selling Singer sewing machines, and working a muffler assembly line at night.

But what Lucas really wanted was a semi. “I’d see these guys going down the road,” he said, “and maybe they were going somewhere. I wanted to get into the truck and go somewhere.” At 21, he pulled together enough money to buy his first semi — the first in what would eventually become a fleet. Two years later, the creek that ran near his childhood farm would be dammed in order to power the nearby city of Bloomington. The entirety of Lucas’s hometown of Elkinton was acquired through eminent domain. His childhood farm was gone, superseded by the needs of those in the city nearby.

Lucas didn’t make his fortune on trucks. He made it on oil additives, created using a “secret formula” that Lucas claims to have discovered almost by accident and which, his company claims, has seemingly miraculous effects on the performance of engines: It reduces wear, lengthens engine life, improves gas mileage, and makes motors run quieter, among other things. Lucas Oil is marketed to car aficionados, gearheads, and truckers with aging rigs.

In the ’80s, Lucas Oil began putting its logo on race cars as a means of advertising. The Lucases bought a cattle ranch in Cross Timbers, Missouri, that has grown to 15,000 acres, with over 3,000 cattle. They opened an oil processing plant in Corona, California, and a second one in Corydon, Indiana, where they also purchased the local railroad. In 2011, Lucas acquired a television channel, MAVTV, and filled it with races featuring cars emblazoned with the Lucas Oil logo. “I realized several years ago that people were starting to [skip] commercials,” Lucas told Autoweek. “We needed to be in the TV show itself, more so than just be on the car.”

Lucas began to acquire the entire means of production: He sponsored the cars, he built or bought the tracks, he owned the broadcasting network, and when the production company he’d employed to make commercials went bankrupt, he bought their gear and trained his loading dock employees to operate it, moving to a dilapidated Sunkist factory in Corona. By 2012, at least 700 different racing teams wore the Lucas Oil logo; today, many of those teams have transitioned to wearing the logo for Protect the Harvest. It’s vertical integration, done the Lucas way: first to promote his oil brand, now to promote his ideological one.

“The thing that’s interesting about Lucas — I don’t think anyone realizes what kind of reach he has,” a correspondent for Speed magazine said in 2012. Apart from the racing, Lucas’s name and brand is broadcast into millions of homes every week via nationally televised games at Lucas Oil Stadium. The $121.5 million gambit, which affixes the Lucas Oil name to the stadium where the Indianapolis Colts play until 2028, launched Lucas and his second wife, Charlotte, onto the radar of the Indiana elite. Suddenly, the farm boy was a person to know.

The Indianapolis elite began actively courting his full-time return from California, where he’d been running Lucas Oil for decades. “Forrest would be a big fish in this pond,” then-mayor Bart Peterson told Indianapolis Monthly in 2007. “He would be somebody who would be noticed, because of his roots, and the fact that he’s proud of those roots.” In 2010, the Lucases purchased a sprawling mansion, known as Le Chateau Renaissance, outside of Indianapolis, with the primary intention to use it for fundraisers and benefits. He added a 220,000-square-foot expansion to his Indiana plant, effectively making it the home base for Lucas Oil operations. Seven decades removed from an electricity-less farm in Elkinsville, Indiana, Forrest Lucas had arrived.

Like many who find their fortunes secure, Lucas decided to throw his newfound influence around. He began donating to political figures — to then-governor Pence, but also to multiple representatives in Missouri, where Lucas ran a cattle ranch. It was there, in 2010, that he took on his first major political fight against Missouri’s Proposition B, colloquially known as the “puppy mill bill.” The bill aimed to limit dog breeding facilities to 50 unspayed/unneutered animals, which would effectively eliminate the “puppy mill” industry in the states where such facilities are most concentrated.

“We’ve got to go on the offense. We’ve got to start staking out ag turf.”

For outsiders, regulating dog breeding and preventing abuses might seem like an easy call, but to dog breeders, it felt like a threat to their way of life. The fight over Proposition B became a proxy for a much larger battle, between animal rights activists — and HSUS in particular — and the agricultural industry writ large. Prop B ultimately passed with 51.59% of the vote — only to be overturned by the Missouri legislature. The struggle over Proposition B emboldened Lucas. Together with other ag producers, he constructed a blueprint for a larger organization that would promote the interests of agriculture. “We’ve got to go on the offense,” Erik Helland, then-majority whip of the Iowa House of Representatives, and one of early architects of this organization, said. “We’ve got to start staking out ag turf.”

In 2012, Protect the Harvest filed paperwork with the FEC to create a political action committee known as the Protect the Harvest Action Fund. Brian Klippenstein — the son of a longtime Missouri state senator, who’d spent the previous five years as then-senator Kit Bond’s chief of staff — became the group’s executive director. While Klippenstein comes from a long ranching heritage, he has the polish and hairstyle of someone who’s spent decades rubbing elbows in DC. According to his Protect the Harvest bio, Klippenstein has “completed over 50 marathons, including over a dozen 50-milers and four single-day 100-milers…all fueled by a high-protein diet centered around nutrient-dense red meat.”

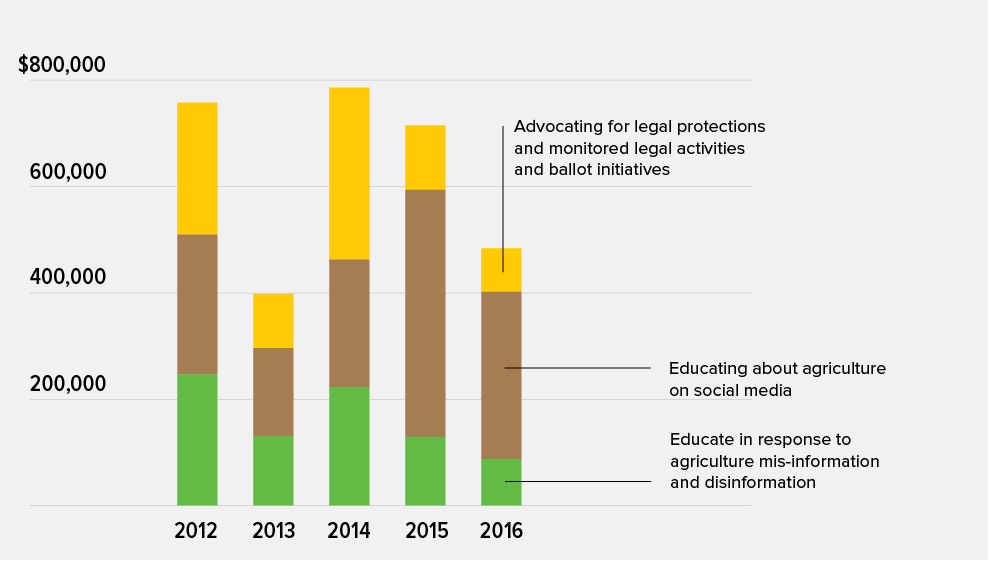

Between 2012 and 2016, the latest year for which tax returns are available, Protect the Harvest Action Fund has spent close to $4 million on influence and lobbying activities. (All tax filings are available here.) Since 2012, the vast majority of Protect the Harvest’s PAC money has been directed toward supporting “Right to Farm” legislation and combating initiatives, most of them spearheaded by the HSUS, that Lucas’s group sees as infringing upon agricultural liberty. The language of contemporary Right to Farm amendments guarantees farmers and ranchers the right to engage in their livelihoods and produce food for others. If that sounds vague, it’s purposeful: It’s less intended to address a current threat than future ones. In practice, it helps bolster the feeling that an industry is vulnerable.

You can get a sense of that perceived vulnerability in a post in ranching publication Drovers, written by cattle genetics specialist Jared Wareham: “Our industry has plead [sic] for a way to help block and then counterpunch anti-ag initiatives and the well-funded organizations that spearhead those efforts,” Wareham writes. “It is unnerving to know that if left unmonitored, these groups could lead initiatives to change the laws of a state or influence the language of those laws so something we have done for a living could be unlawful. If these organizations can win battles in one state, it could easily open the door to successes in other states.”

And who happens to be defending the industry from this alleged war? Protect the Harvest, which Wareham describes as “the shield of armor we’ve been looking for.”

Protect the Harvest’s first foray into the fray came in Missouri, where it offered broad media support for a 2014 Right to Farm amendment, copied from a 2012 version drafted in North Dakota. For that campaign, Lucas enlisted then–state senator Mike Parson, who is now governor, and to whom Lucas has given more than $175,000 in campaign donations. The two men first connected in 2010, during the campaign against Proposition B. After it passed, Parson, whose district included Lucas’s cattle ranch and one of his speedways, sponsored the legislation that effectively defanged the bill. From 2013 to 2015, Parson served as the treasurer of Protect the Harvest, and when Parson ran for lieutenant governor in 2016, Lucas and his wife campaigned alongside him; after he won, he framed a Protect the Harvest poster in his office.

In North Dakota, the Right to Farm amendment had sailed to an easy victory, winning two-thirds of the vote. But in Missouri, it was hotly contested. One public radio story framed it as pitting “farmer against farmer,” leaving little way for small producers to defend against the incursion and growth of larger ones. Protect the Harvest argued, “Our rights don’t come from government. They are God-given freedoms that come with our humanity. However, bureaucrats and activist judges have made it clear that they will not respect those rights unless they are codified in statutes or constitutions.” Together, both sides spent a total of $1.5 million on messaging. The amendment barely passed, eking out 50.12% of the final vote.

A version of the amendment then migrated to Oklahoma, where Protect the Harvest was joined in support by the Oklahoma Cattlemen’s Association, the Oklahoma Farm Bureau, and the Oklahoma Pork Council. Their opposition, led by HSUS, the Sierra Club, the ASPCA, and the Oklahoma Food Cooperative, argued that the bill, SQ 777, would make it impossible to act if and when ag polluted or otherwise threatened a water source or the land.

“I work with family farmers from all over the state,” said Adam Price, a representative of the Oklahoma Food Cooperative. “And I can say with absolute certainty that SQ 777 was not conceived with them in mind.” The “yes” argument was crystallized in a television ad created by Protect the Harvest: “Have you seen the ads attacking 777? ALL LIES. Paid for by the same out-of-state animal rights groups that oppose the right to hunt and fish.”

In the end, the Yes side lost by 20 points — the first major defeat for the new wave of Right to Farm legislation and Protect the Harvest. Brian Jones, an attorney who spent a year working for the “no” side, links the amendment’s failure to reactivated memory: “Most people in Oklahoma have an agricultural heritage, meaning their grandparents or parents were farmers,” he told BuzzFeed News. “One of the consequences of the industrialization of ag is that fewer and fewer people are involved in it. Most of what is out there, in the market right now, is Big Ag.”

During this same period in the ’90s, there was enormous consolidation in ag production — basically, big farms buying up smaller ones — that marked an end to many farming families’ way of life. “There were some fights about all this back then,” Jones said. “But 777 reraised all these questions: Where did the jobs go? What happened to the people?”

In Missouri, Protect the Harvest had effectively mobilized those rural anxieties, papering over the role of larger industrial and legislative forces that had ended that way of life years before. In Oklahoma, that project failed — but their defeat has only served to bolster Protect the Harvest’s argument that outsiders are determined to fight against one’s “right to farm.” (In an email to BuzzFeed News, a spokesman responded to a question about the effects of deregulation on small farms with the following statement: “Protect the Harvest supports all forms of agriculture. Our mission is to educate and inform the public about issues that impact our American traditions, heritage and way of life. There are many overreaching regulations that impact farms, both large and small which ultimately affect the American public as both large and small farms feed our nation.”)

Lucas’s design to “protect” the harvest has largely entailed fighting regulation. Like many conservative operatives, Protect the Harvest views any type of regulation, whether on the hours a long-haul trucker can legally drive or the conditions for raising chickens, as unnecessary and restrictive incursions on free enterprise, but one area of particular interest has been wild horses.

Back in 2012, Dave Duquette attempted to bring a horse slaughterhouse to his hometown of Hermiston, Oregon, promising much-needed economic stimulus to the area, but local leaders balked at the prospect of the town being equated with a taboo industry. Fast-forward six years, and Duquette is the “equine specialist” for Protect the Harvest.

Duquette, who is rarely without his cowboy hat and a cowboy shirt embroidered with the Protect the Harvest or Lucas Oil logo, has spearheaded Protect the Harvest’s efforts to change the messaging around wild horse management from cruelty to benevolence.

“It was really scary to be targeted by that machine.”

“American wild horses are suffering due to overcrowding, which has led to starvation and death,” the opening to a four-part series on Protect the Harvest’s homepage claims. “We have the opportunity and obligation to protect them from long and painful suffering by controlling their numbers.” A 15-minute PTH-produced video, titled “Horses in Crisis,” features an array of sick and starving horses, as well as ranchers and others condemning “horse advocates” for their lack of knowledge about horses on the range. “It’s time to bring facts, reason, and a special perspective to an issue dominated by emotion,” a solemn-voiced narrator says. The overarching message: Those who deal with wild horses on the land should dictate how to manage horses on the land, and not faraway regulators.

That was Duquette’s message in 2015, when he visited Nevada in support of a rancher named Kevin Borba, who had repeatedly and progressively flouted rules governing the treatment of wild horses on his grazing allotment. Duquette posted a picture of Borba in a Protect the Harvest–branded four-wheeler, out to “document” the “lies” spread by Laura Leigh, who was heading up an experimental fertility control program on the horses. Protect the Harvest created a series of videos framing Borba as a victim of the BLM, whose “mismanagement hurts both the horses and the ranchers whose livelihood are being taken away.” According to Leigh, an initial version of the video, later taken down, included her name, prompting immediate harassment. (Protect the Harvest disputes this claim.) “I was getting a dozen death threats with my morning coffee,” Leigh told BuzzFeed News. “It was really scary to be targeted by that machine.”

Lucas has repeatedly referred to HSUS and animal rights activists as “terrorists” intent on “passing laws to ruin America” that deliberately impugn the small-time farmer’s way of life. Lucas’s political donations and Protect the Harvest’s messaging around ballot initiatives underlined that ideology. But to make those ideologies even more robust and persuasive required something more effective than political ads. They needed propaganda.

Propaganda is anything from a pamphlet to a television program that attempts to make an argument for a particular political stance, whether on the right, left, or center — but much of it can be heavy-handed, simplistic, or misleading. When it comes to agriculture and animal rights issues, both sides of the issue produce propaganda. But only one side has its own film studio.

When Lucas first started producing television programming for his television channel, the focus was vehicles to broaden his company’s name recognition. “We got into the entertainment business to sell oil,” Lucas once said. “And nothing is more entertaining than fast cars, trucks, planes, and boats.” By 2015, his intentions had expanded. “For me, venturing into the film business is not about money, glamour or fun,” Lucas said. “It’s about being able to deliver messages and having a viable vehicle to do so.”

“For me, venturing into the film business is not about money, glamour, or fun. It’s about being able to deliver messages and having a viable vehicle to do so.”

But what sort of “messages” did Lucas want to transmit? Protect the Harvest messages. Last year’s Pray for Rain, starring Jane Seymour, suggests that corrupt environmentalists, in league with shady gangsters, are prolonging the terrible drought afflicting Central California and threatening the livelihoods of desperate local farmers. Running Wild, also from 2017 and starring Sharon Stone — who also coproduced — depicts a wild horse advocate, whom Laura Leigh believes is loosely based on her, as an evil villain trying to shut down a horse rehabilitation program. The 2016 film The Dog Lover, featuring Lea Thompson, involves a young woman who volunteers with an animal protection group to go undercover at a puppy mill — only to discover that the organization is far more dangerous than the “mill” itself, which, turns out, is actually a kindhearted breeding operation.

ESX films are regularly panned by critics, do not receive theatrical releases, and go straight to video or VOD. But profits, according to Lucas, are secondary. They’re reaching an audience: ag families who don’t feel that their way of life is represented accurately onscreen, and those who may not know a thing about agriculture but will be called upon to vote or think about the issues represented in the films. Watch The Dog Lover, for example, without much understanding of the dog breeding industry, and it’s easy to believe that “puppy mills” are an idea concocted by manipulative animal rights activists who have no idea what they’re talking about.

The feature films are only one arm of Protect the Harvest’s messaging apparatus. Back in 2014, Lucas commissioned a documentary about his life (produced by advertising company MARC USA), which screened at the Heartland Film Festival. (Earlier that month, Lucas’s wife, Charlotte, had drawn national attention for a Facebook post, later deleted, that declared, “I’m sick and tired of minorities running our country! As far as I’m concerned, I don’t think that atheists (minority), muslims (minority) or any other minority group has the right to tell the majority of people in the United States what they can and cannot do here. Is everyone so scared that they can’t fight for what’s right or wrong with this country?”)

The day after the Facebook post, Lucas — who has previously acknowledged that his workforce is largely composed of immigrants — issued a full-page apology in the Indianapolis Star for his wife’s post, explaining that it did not “reflect the feelings in her heart,” and underlining that Lucas Oil “is proud to have employees, friends, customers, and business partners reflecting ethnic and racial diversity.”

Apart from the films, Protect the Harvest maintains a robust Facebook presence: Its page currently has 258,000-plus followers and posts links, petitions, editorials, and memes five or six times a day. The Protect the Harvest website features links to civics workbooks that can be suggested as additions to local curriculum; at the bottom of the first page, a logo declares, “You could be forced to give up your freedom to hunt, fish, and own animals. Learn more at ProtectTheHarvest.com.” For class activities, the workbook suggests observing the judicial branch at work in movies like To Kill a Mockingbird, My Cousin Vinny, or Protect the Harvest’s own The Dog Lover. For kids, there’s a section of downloadable coloring sheets bordered with “PROTECT YOUR PET! PROTECT AMERICA! PROTECT THE HARVEST.COM!”

In Range magazine — an independently owned quarterly publication full of beautiful rural landscapes and essays about how “the U.S. government has inflicted 40 years of abuse on Nevada’s Hage family” — Protect the Harvest now occupies about half of the ad space, promoting Protect the Harvest films and the Hammond pardon. Partnering with Range, Protect the Harvest has helped fund three “Range Rights” conferences — in Layton, Utah; in Bellevue, Nebraska; and in Modesto, California.

The two-day conference was founded in 2015 as a way to harness the energy following the Bundys’ Malheur occupation; attendants include a mix of Malheur devotees and local ranchers. In Modesto this April, the attendance hovered around 40, and half the attendees were speakers themselves — but the real range rights audience was online, where each of the speeches was streamed in full. Rep. Devin Nunes, once part of the House Intelligence Committee’s Russia investigation, attacked the press; the local sheriff emphasized that his officers knew to look the other way when local ranchers had an unlicensed firearm. The daughter of LaVoy Finicum spoke about the legacy of her father, the rancher who was killed by Oregon State Police in what have become heavily contested circumstances, effectively rendering him a martyr for the Bundy movement. Finally, Ammon Bundy preached the latest chapter in the family’s gospel, emphasizing that environmentalists are “an enemy to humans” practicing their own heretical religion.

The entire event was hosted by Trent Loos, a Nebraska farmer, member of President Trump’s Agricultural Advisory Committee, and one of Protect the Harvest’s most visible activists, united with Lucas in his fierce opposition to HSUS. (When HSUS began using Michael Vick’s role in dogfighting and other forms of animal abuse to make the case for tougher legislation, Loos wrote that Vick was being persecuted for “not ... treating his dog like a kid.”) With his bushy mustache and ranching vest, Loos — who pleaded no contest in 2005 to charges of cattle fraud — looks the part of the cowboy, and will play one in a forthcoming PTH film. In Modesto, Loos took the stage with Nunes. “As a member of the ag committee, we have a certain level of frustration that we haven’t drained the swamp quicker, that we still have old-school bureaucrats in the positions of decision-making,” he said. “So how do we get that fixed? Because obviously there’s a bigger plug in the swamp than anticipated.”

At that point, Protect the Harvest had been working to “unplug” the swamp for well over a year. When journalist Michael Lewis began investigating the transition officials appointed by the Trump administration, he zeroed in on Brian Klippenstein’s USDA role. In an interview with Fresh Air, Lewis described Protect the Harvest as an organization that sees its job “as essentially trolling the Humane Society,” and is “hypersensitive to animal rights people and tries to respond to animal rights activists wherever it can.” USDA employees found Klippenstein’s appointment odd because, as Lewis put it, “one of the things the USDA does is stand up for the rights of animals in animal-people disputes.”

Dogfighting, circuses, animal slaughter, animal testing — the USDA is charged with documenting and monitoring those operations. In the subsequent weeks, Klippenstein alone took on the responsibilities of a transition team that usually would’ve been entrusted to a team of at least 20. Through his briefings, he became intent on figuring out which of the existing Department of Agriculture employees had been researching climate change and its ramifications.

The request was denied, but Klippenstein made his mark in other ways. He now serves as a senior adviser to Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue, who has overseen the removal of USDA documents detailing past animal inspections, enforcement actions, and annual reports on 7,800 different facilities. The removal was prompted by a lawsuit, filed during the Obama administration, alleging that a report identifying Tennessee walking horse owners as “violators” of anti-soring regulations impinged on their rights to due process and privacy. To address the suit, Perdue has removed all records.

According to Duquette, Lucas first brought up the idea of a pardon to then-governor Pence before Trump’s election.

The move was celebrated by Tennessee walking horse groups, but it has broader beneficiaries: practitioners of industrial agriculture, whose husbandry, living, and slaughter practices are also monitored by the USDA. The lack of publicly accessible monitoring records will make it increasingly difficult to prosecute, legislate, or otherwise regulate current agricultural practices.

“We’re lucky with the things this administration has been doing,” Duquette told BuzzFeed News. “It’s been really good to deal with, and find problems to fix. That’s probably been the best thing to happen for animal agriculture, the pet industry, and the food supply.”

This sort of access and influence helps explain how the Hammonds’ appeal made its way to President Trump’s desk. According to Duquette, Lucas first brought up the idea of a pardon to then-governor Pence before Trump’s election. When Lucas and Pence had dinner in May, Lucas brought up the case again, making the argument for a commuted sentence. Soon after, the case was moved to the office of Pence’s chief counsel.

“You know, it’s ‘a squeaky wheel gets the grease’ deal,” Duquette told BuzzFeed News. “And I know the president needs help from people to highlight injustices.” Since late May, Protect the Harvest’s social media accounts have been in overdrive eliciting popular support for the Hammonds’ cause. Protect the Harvest has also moved to distance itself and their cause from the Bundys, who’ve been grouped with the Hammonds since the days of the standoff.

Indeed, Duquette believes that if the Malheur occupation hadn’t happened, the Hammonds would’ve been pardoned long ago. “I don’t disagree with [the Bundys’] issues, but the tactics are...” he said, pausing for a moment. “I understand the tactics because of their frustration with what they’ve had to deal with over the years.”

During the occupation, Duquette and Trent Loos posed for a photo with Ammon Bundy; while a representative from Protect the Harvest has denied offering material support to the occupiers, Todd Macfarlane — a lawyer, Bundy supporter, and standoff spokesperson — blogged that Protect the Harvest had made “its people, resources and checkbook available.” Protect the Harvest counters that a representative “went to Malheur Refuge one week into the occupation to do an interview with Ammon Bundy.”

But as the Hammond petition made its way to the White House, Duquette told BuzzFeed News that he called Ammon Bundy to let him know that Protect the Harvest would be publicly distancing itself from the Bundy family. Still, the Bundys threw themselves behind the pardon petition, posting multiple links to it. When the news was announced, the Bundy Ranch Facebook page’s post alluded to the connection: “Thank you @POTUS for carrying out justice and pardoning Oregon ranchers Dwight & Steven Hammond. Many ranchers in the West have suffered under the heavy hand of the federal government. These men are great patriots.”

Pardoning the Hammonds suggests not only that this particular case was mistreated, but that fears of government are warranted.

Duquette acknowledges that a Hammond pardon will be treated as a win for the Bundys and their supporters. But that’s not necessarily a bad thing, he said. “The president would have an outpouring of support in the West, and throughout the Midwest, from all the people that are his base for doing this. It would show a good sign of goodwill for all the people out there.”

To pardon the Hammonds is to ratify that their case, like so much of what Protect the Harvest lobbies against, is an example of federal overreach — engineered by ignorant outsiders who resent and misunderstand the people who make American life possible. As Montana Rep. Greg Gianforte phrased it in a public statement, “President Trump’s decision to pardon Dwight and Steven Hammond is a win for property rights and our way of life.”

But like so many of the issues on which Protect the Harvest’s advocacy pivots, the reality is far less stark. The Hammonds were sentenced for committing arson on federal land. An appeals court vacated that sentence because it did not satisfy the mandatory minimum sentencing requirements, and resentenced them for the mandatory minimum for that crime. Apart from the back-burning, the Hammonds have a long history of taunting BLM management and flouting their regulation. Like the Bundys, the Hammonds have long believed that the federal, public land they pay pennies on the dollar to graze should be considered their own, to manage as they please — including setting fires. The federal government, at least for the time being, disagrees.

Pardoning the Hammonds suggests not only that this particular case was mistreated, but that fears of government overreach are warranted — and that Trump will continue to act in a way that acknowledges those fears.

All over ag country, Oregon to Arkansas, small schools are closing their doors. Part of the reason is that the consolidation of agriculture — larger farms gobbling up smaller ones to stay alive — has made it impossible for those onetime small farmers to remain. The population of the small town dwindles, and the schools close, which makes it even less desirable for others to move to that town, provide services, attract jobs, or maintain the “way of life” associated with rural America.

When you look at the Protect the Harvest logo, you don’t see a family. You don’t see a way of life. You don’t see a person at all. You see a combine harvester — one of the primary advances in farming technology that led the agricultural industry to the place it is today. “All of their imagery is of big, beautiful tractors churning through a commodity crop, essentially dripping Lucas Oil,” Ryan Bell, a journalist and close observer of fights around the agricultural way of life, told BuzzFeed News.

“But that tractor, that’s what took the community away from ranching. It undercuts a long-term, sustainable agrarian society,” he said. “There’s no need for a big family to work the farm, and no need for the family you have to stick around. Today, a man might have a thousand acres of corn, and he’s tilling it all alone with a $250,000 combine. His kid’s gone. And oddly enough, this is exactly the type of person who’s pretty susceptible to Protect the Harvest rhetoric.”

There are dozens of intersecting reasons for the end of the agrarian way of life. Some of them stem from bad legislation, improper federal regulation, and advocacy from groups with little sense of the larger effects of a disruption in the food chain. There is an impending food crisis in the world’s future. To solve it, however — while also preserving the Earth long enough for our descendants to confront that crisis — all sides of the issue need to spend less time creating bogeymen of the others; less time on “offense” or “defense.”

The production of food may be an industry, but it’s not a game. Whether in the form of government subsidies or a vaunted position within the American imaginary, the harvest has been protected for centuries.

Taken separately, Protect the Harvest’s initiatives — the feature films, the fight against HSUS, the move to root out those studying global warming, the Right to Farm advocacy, the Hammond pardon — none of it seems, on its face, like a means of protecting business interests. It’s only when examined together, as part of a larger, motivating whole, that Lucas’s actual passion becomes clear. It’s not the small-time farmer. It’s certainly not the harvest. It’s not dogs, or hunting, or horses. Forrest Lucas prides himself on his identity as an all-American man. And nothing is more all-American than unfettered industry, and the profits that flow from it. ●