While the U.S. government was negotiating with Taliban representatives on the controversial prisoner swap that set Sgt. Bowe Bergdahl free, Bergdahl's family opened up a separate channel to the Taliban to try to buy his freedom with cash, according to two sources with knowledge of the case.

This channel of negotiations has not been previously reported. It was focused on winning Bergdahl's freedom with a $10 million ransom to be paid by private sources, not U.S. government money, the sources say. These talks started in 2012 and continued until May 2014.

The revelation of this second set of negotiations underscores two points: Bergdahl might have been freed without the release of the five Taliban from the Guantanamo Bay detention camp, and the Taliban are still driven heavily by the need for cash.

BuzzFeed's account is based primarily on two individuals, one of whom is familiar with the Taliban's thinking. Both spoke on condition of anonymity. They said that Robert Bergdahl, the father, pursued this channel with vigor. "The father managed everything," said one of the sources. "He held it close to the vest," said the other.

Robert Bergdahl, the soldier's father, did not return calls for comment. However, David Rohde, an American journalist who was himself held hostage by the Taliban in 2008, communicates with the family regularly and asked the father about the second channel of negotiations described by the two sources. The father, he said, acknowledges setting up "multiple channels" to the Taliban, because he was willing to try anything to free his son. But the father, a retired UPS worker, insisted that he did not take this effort seriously, that there was never an actual ransom price discussed, and that he never raised money for a ransom.

In the early days of Bergdahl's disappearance in 2009, it became clear that he was in the custody of the Haqqani family network, one of the most fierce and powerful groups in the Taliban. "The Haqqanis are in the kidnapping business, they sell people," said Michael Semple of the Institute for the Study of Conflict Transformation and Social Justice at Queens University in Belfast. Though not involved in the Bergdahl negotiations he is an expert on the Taliban and knows many of the players on both sides. "They are involved in kidnapping for ransom."

An initial demand for ransom from the Haqqanis was ridiculous, the source familiar with the Taliban's thinking said: To free Bergdahl, the group wanted 50 prisoners released and $25 million in cash on top of that.

But soon there was a shift in the negotiation process, and the main Taliban leadership, known as the Quetta Shura, took control. The Quetta Shura, according to experts on the group, has a "prisoners commission" that deals with hostages, prisoners of war, ransoms, and exchanges.

Diplomats in Germany initially helped to broker talks with the United States. The government of Qatar became a key intermediary.

The list of Taliban demands was scaled back solely to prisoners, rather than money, and the focus was on the Gitmo prisoners, the same five who were eventually released. The most serious of these was Muhammed Fazl, who had been the Taliban army's chief of staff before the United States invaded Afghanistan.

The formal talks between the United States and the Taliban were plagued with fits and starts. In 2012, for example, the two sides communicated sporadically and only through Qatari intermediaries, not directly. At that time, the United States was in the midst of a heated presidential election.

One major glitch from the beginning: The United States wanted to paint a prisoner trade not as simple quid pro quo, but as a part of peace talks to end the Afghan War and reconcile the Taliban with the Afghan government. A former U.S. official told BuzzFeed that to the Americans a prisoner exchange was seen as "leverage to start a peace process."

But that complicated things. "If the objective three years ago was solely to get Bergdahl home, the last thing you would have done is tie it to lots of issues," Semple said. "It was a glitch in terms of getting Bergdahl home, but that doesn't mean it was a stupid idea."

All along, another major obstacle, sources say, was the timetable for freeing the prisoners. The United States wanted to stagger out the release of the men from Gitmo, letting one Taliban leader go and then, months later, the next, and so forth. But this proved unacceptable to the Taliban.

The source familiar with the Taliban's thinking said some members of the group came to believe that the U.S. government would never release prisoners in exchange for Bergdahl.

In 2012, the Taliban prisoner commission indicated to a private intermediary that it would accept a financial ransom rather then the prisoners it wanted so badly. The intermediary was a man based in the Middle East who has extensive ties to Afghanistan and to the West. At first the price was $15 million for the release of Bergdahl, one of the two sources said. But gradually, the price declined.

The father, according to those know him, was frustrated at the slow pace of the official government efforts. In 2012, Robert Bergdahl hinted at his approach to the Taliban in an interview with the New York Times. "Mr. Bergdahl said that he had started to deal directly with the Taliban by e-mail in recent months," the New York Times reported back then, "initially through a 'contact us' tab on a Taliban website, but then through a member of the Taliban he believes has knowledge of his son's circumstances." The article does not mention a ransom in that context, though.

The Taliban used its time-tested method of dealing with hostage negotiations: It used the intermediary in the Gulf region who was trusted by both parties. Then it provided a "proof of life" letter written by Bergdahl to demonstrate that he was still alive and that the negotiations were legitimate.

Bergdahl's family sent a message back to the Taliban through this channel. The family included a letter signed "Papa and Yaya," one of the sources familiar with the case said, encouraging Bergdahl to be cheerful, and they included a photograph of themselves. Bergdahl's father separately sent a note in Arabic to his son's captors quoting sections of the Qur'an.

It's unclear how much, if anything, the U.S. government knew about this channel. One former American official involved in the formal negotiations was dismissive of the father's outreach. "There was nothing serious about those efforts," he said. "They were not plausible. There is always background noise in things like this. It wasn't serious enough to merit attention."

In June 2013, the Taliban opened an office in Qatar to facilitate the Bergdahl prisoner-swap negotiations with the U.S. The office was also supposed to spur forward peace talks.

But the Taliban overplayed its hand by giving the Qatar office the trappings of an embassy, putting up a sign identifying it as an office of the "Islamic Emirate Of Afghanistan," and flying the old Taliban flag. The Afghan government was furious and raised complaints, so the office closed and the prisoner-swap talks again seemed moribund.

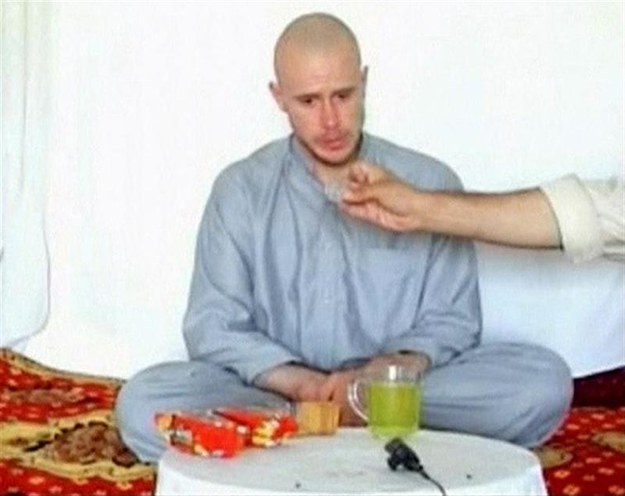

In the fall of 2013, the formal prisoner-swap talks came to life again. The Taliban office stayed closed, but Taliban representatives still remained in Qatar. That December, Bergdahl's captors made a video, and sent it along to the American government through that official channel. It appeared to show the soldier weakened and barely able to function.

Now the Taliban negotiated on both fronts, for the cash on one hand and for the prisoners on the other, as if hedging their bets.

The cash, at least to the two sources familiar with this channel, seemed to be winning out. "These financial negotiations were more advanced then the prisoner talks," one source said. "They were really close to getting this done," said the other.

But there were still plenty of unknowns, including how Bergdahl's father would have raised the ransom money if a deal had been reached. One theory is that a friendly government in the Middle East would have contributed the cash. And even if the deal were struck, could the actual release have gone through?

The official efforts had a sudden breakthrough in May, though it is still unclear exactly what made the deal go through after it had been delayed so long. The Guantanamo five were flown to Qatar, and Bergdahl was handed over to American forces.

And that's when the controversy started. The U.S. Army is still investigating how he was captured in the first place, and Congress is probing the prisoner swap. The family, for now, is declining interviews.