Is it too late to identify with Mitt Romney?

Of all of the Republican nominee's many problems during what amounted to a six-year, nonstop failed campaign for president, none did more damage than the fact that most Americans seem to have found it impossible to see their own lives in his, even a little bit. This bit of conventional wisdom found striking validation in the exit polls: Obama won 81% of the fifth of Americans who said that the quality that matters most is that a candidate "cares about people like me."

Romney's many stumbling blocks are familiar. He chose to virtually never talk about three of the four most important things in his life: his faith, Bain Capital, and the Massachusetts governorship. He talked about his family constantly, but almost never about the serious problems and conflicts most families have. His wealth may have made him remote. His frugality, and pride in not having benefitted from his father's wealth, was even stranger: Most Americans who aspire to great wealth probably don't then plan on continuing to wash their clothes in the sink. His hair was always perfect.

Romney also never managed to project something that is familiar to most people, and which has made many other candidates sympathetic: defeat. He had, in fact, faced real setbacks, from a harrowing car wreck as a young man to losses in two high-profile campaigns, for Senate and president. But Romney's response — to keep his head high, to return to business, and evidently never to look back or mope — made him seem like the stiff-upper-lip hero of a Victorian novel. In 2012, the most powerful Republican in Washington, John Boehner, seems to weep constantly. But Romney's life, in his telling, had less an arc than a straight, 45-degree upward slope.

That approach seemed to reject — and repel — sympathy. The new images of Romney that have redefined him to a public he is largely avoiding, by contrast, compel sympathy.

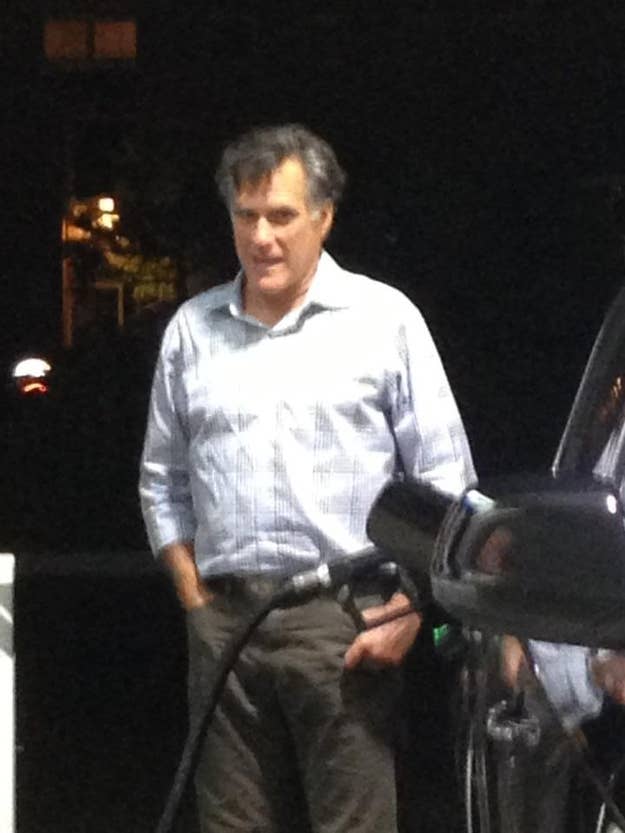

Here he is at a gas station in La Jolla, hair notably imperfect. "[H]e looks tired and washed up," wrote the redditor who snapped it.

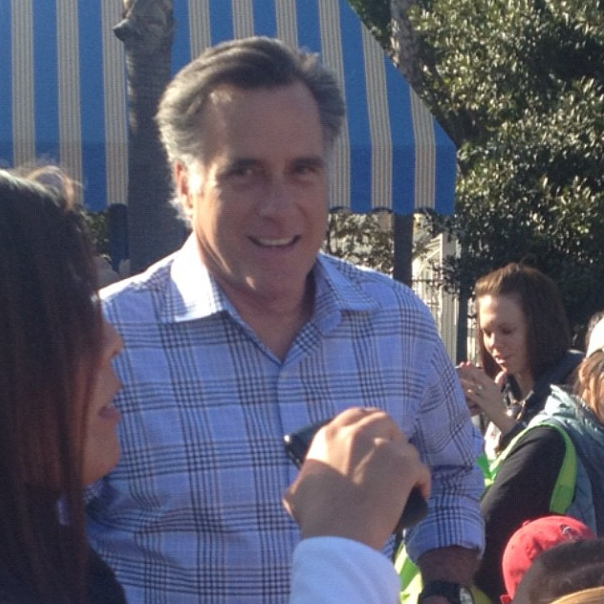

There are cameras everywhere, and Romney's Nov. 20 visit to Disneyland with his sons and grandchildren was extensively documented. He looks, in it, as you'd expect to: He's escaping, having fun with his grandchildren, resigned to the curiosity-seekers.

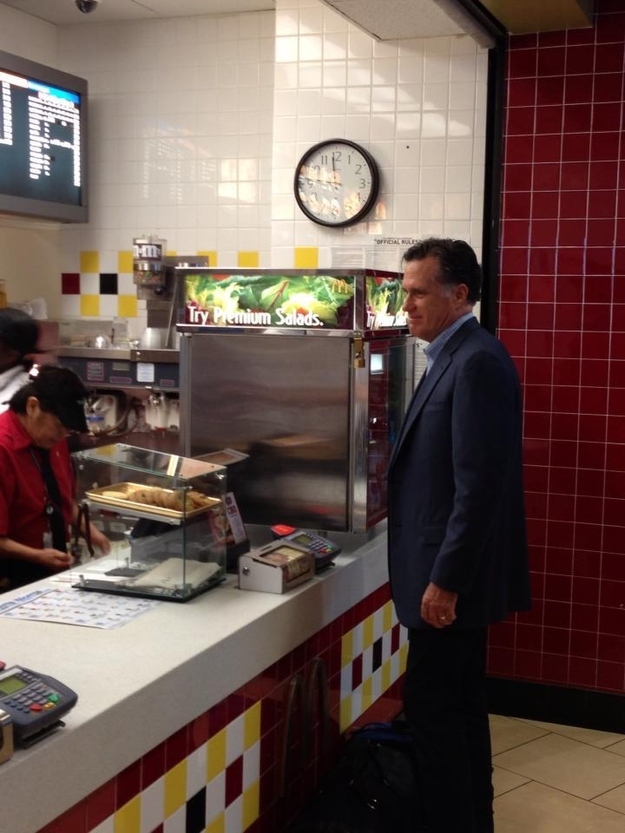

On the campaign trail, Romney's staff constantly put out word of his populist tastes. He wore cheap clothes and ate cheap food. And in the campaign context, these felt like affectations, and like spin. Staff tweeted these images and read out his fast-food orders to reporters, to counter the Daddy Warbucks perception; the result was to reinforce it.

Now he's a guy who had a bad month, finding a little consolation in eating alone at McDonald's.

The Washington Post's Phil Rucker reports that Romney is, in fact, basically moping. He's living in La Jolla, a tony California beach town, riding his bike around. There, he appears to something of a local curiosity, something perhaps a bit short of celebrity. The Twitter traffic on Romney sitings is sparse; the main reaction to seeing the man who could have been the most powerful man in the world is "lol."

But there's sympathy mixed with the schadenfreude: "Leave him alone. He has to start a new life. In all fairness wish him luck," one person tweeted. This is what candidate Mitt Romney, who began running while he was still governor of Massachusetts, never really had — any basic reason not just to admire him, but to identify with him, even to pity him a little. He was a throwback in this way too, running for president of a 1930s America where Franklin Roosevelt had to pretend he could walk unassisted. The America of the last two decades, at least, has been one where authenticity trumps perfection. Barack Obama's splintered family and quest for identity; George W. Bush's drinking problem; even Bill Clinton's appetites were reasons to like the men and to vote for them. Had Romney been elected, he would have been the first president to project that sort of superficial flawlessness since, perhaps, Kennedy.

This is not to suggest that Romney could have made some tactical correction to make himself more relatable, or that Stu Stevens misread the focus groups. In the end, Romney did the only thing he could to make people like him: He lost.