On the Sunday before the big game, superagent Leigh Steinberg is a busy man, but not in the way you'd expect. Yes, he has his bags packed ready to head to New York City to host his annual Super Bowl party. Today, however, he's standing at a podium in a West Hollywood bookstore before a sparse crowd. Steinberg is promoting his latest book, The Agent: My 40-Year Career Making Deals and Changing the Game, which chronicles the rise and eventual fall of the man whom Cameron Crowe followed for two years before making Jerry Maguire.

Steinberg grew up in Los Angeles rubbing elbows with Hollywood legends at the Hillcrest Country Club, which his grandfather managed. He burst onto the sports scene in 1976 while attending Berkeley School of Law. His first client, Steve Bartkowski, was the No. 1 overall pick in the 1976 NFL draft.

By the late 1980s, Steinberg was one of the game's major power brokers. He represented Super Bowl-winning quarterbacks like Troy Aikman and Steve Young, running backs Thurman Thomas and Ricky Williams, and Hall of Fame defensive end Bruce Smith. Steinberg, a noted philanthropist, also made a name for himself by helping set up charities for his clients, work for which he received commendations from four American presidents. He eventually sold 30% of his company to Canadian financial management firm Assante Sports Management Group for reportedly over $120 million.

Then came the troubles. Even as his professional life prospered, by the mid-2000s, Steinberg's personal life started to crumble. Between a lawsuit with Assante that left many of his younger agents upset, and trouble at home, things decayed. Steinberg became depressed and a drinking problem spiraled out of control. He faded from the scene he once dominated.

Now sober, the 64-year-old is starting fresh, publishing the book and hoping to resume his career with the same commitment that made him a star to begin with.

What was it like growing up in Hollywood with some of the original giants of the film business?

Leigh Steinberg: They were just funny old men to me. I thought the whole world was old Jewish comedians. When you're sitting there and Groucho Marx is trading stuff with George Burns and they're going back and forth, it seems surreal now, but at the time it was very funny. I didn't know who Marilyn Monroe was when I was sitting on her lap, and I got an Elvis Presley autographed guitar and I barely knew who he was too.

You stumbled into getting your first client, Steve Bartkowski, when you were in law school at University of California, Berkeley. Did the clients start flocking to you after he was picked first overall?

LS: Not until I learned how to profile players. When I learned that it was a certain type of player who was willing to serve as a role model and who was more ambitious than others, who wanted to springboard from football into a second career. I was very interested in those players who wanted to start their own charity. The ability to profile and research players and to find what people would be open to this approach, that's when I started building something. It goes back to my father. We weren't raised to be money people. We were raised to be making-a-difference people. I wanted athletes who reflected my own values.

When did things start taking off for you?

LS: Steadily. I signed a number of first-rounders through the years. I started developing quarterbacks as a niche. In 1983 I had Ken O'Brien and Tony Eason in the first round, but '84 was a dramatic year. The USFL [United States Football League] was competing, and that pressure and competitive bidding always explodes options. Warren Moon had been in Canada for six years and we timed his return so the USFL, the CFL [Canadian Football League], and the NFL were competing for him. There had never been a free agent in football before. So to have a player that was actually available with no draft picks, no trade, and you could just sign him at the most critical position, who was in his prime — it was unusual. You could just take him right in and play him, and it would cost you nothing besides his contract. We ended up with the largest contract in the history of the league with Houston.

What about Steve Young?

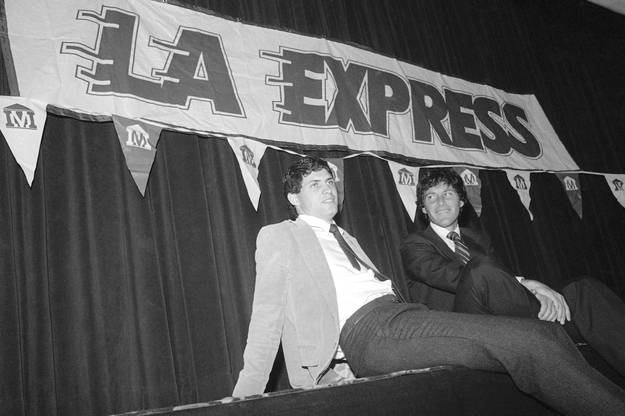

LS: They needed a quarterback in L.A. [for the USFL's Los Angeles Express] since it's such a star city and all the rest. I'm negotiating the contract, but the problem is Steve really wants to play in the NFL. So as we're negotiating, I keep saying no and the dollars are getting astronomical and we're finally at a point where no one has signed a sports contract like that before. It ends up being $42 million for four years. When we signed, it was front-page news around the world and Steve was aghast because he's being held up as a sign of excessive sports economics run amok.

Things really got cooking, though, in 1989.

LS: That's when I signed Troy Aikman as the first pick, and that sets a roll off where we do '89, '90 [Jeff George], and '91 [Russell Maryland] with the first pick in the draft. We miss a year, and do '93 [Drew Bledsoe], '94 [Dan Wilkinson], and '95 [Ki-Jana Carter]. At that point, I've done the first pick in the draft six out of seven years, which is impossible. No one will ever do that. I just kept stockpiling quarterbacks, and at one point I had 21 and half of them were starters. Eventually, I had a practice with 90 players and over 80 had been to the Pro Bowl.

Were you involved with any other entertainment ventures besides, famously, Jerry Maguire?

LS: I was a technical consultant for Oliver Stone's Any Given Sunday and For the Love of the Game. There was also Arli$$, which I didn't let them use my name on. I gave them my worst stories — it's the anti-me! I had Arliss go after a client's wife. That's a good way to get killed! I gave them a story where he represented every side of a franchise move so he had hidden interest with the city, the stadium authorities, the buyers, every side.

When did things start slipping?

LS: We sold our business for over $100 million and I was financially set for life, but we had a fight that happened in our firm in 2001. Then, my father dies a long death of cancer. He was a central figure in my life. My two children were found to have major vision problems. We lost a home due to flooding and had to knock it to the ground. And lastly I got divorced. I was crushed. I felt like a series of events kept happening that I couldn't protect my father, my kids; hold my marriage together; or save our house. So I started to drink heavily. I was one-beer Steinberg; I came out of a Jewish family where there was no alcohol, and I wasn't a heavy drinker. But it was legal. The truth is what we did at Berkeley would have been better, but it was illegal and that's the problem. I had to move into the first apartment I'd ever owned by myself. I was crestfallen and I learned you could drink during the day, which I didn't know was legal. In 2007, 2008, 2009, it spiraled. I didn't go drunk into the office, but I would take days off. I'd get to 2010 and I gave the younger agents the practice. I moved up to my parents' house in west L.A. and my greatest idea was to drink more vodka. That's how I had a moment of clarity and realized I wasn't fulfilling any of the admonitions of my dad. I got into a 12-step program, got a sponsor, and withdrew from the world. Being successful in the world wasn't difficult, it was dealing with these personal things, and I felt powerless. Like Gulliver tethered down on the beach having forks stuck in him. I didn't want to die; I wanted to get some relief.

Were there warning signs? There's the incident at Drew Bledsoe's wedding where you were allegedly drunk…

LS: Honestly, the lawyers put Bledsoe up to talk about that. Everyone was drunk. I was drunk, but so were his mother, his father, his wife, and the people reporting the story. We lived in the Disneyland of drinking. Most of my drinking, honestly, was late at night when my marriage disintegrated. But when I got started, I caught up quick. I wouldn't have understood it prior how the reptilian brain takes over, so you're way away from the rational part of your brain. At the end, it equates the need to drink with every other basic instinct and it sends out cravings so strong it overruns the rational thoughts you have and there's no off button. With the Bledsoe stuff, a lot of it comes from them defending themselves with hostile environment; I was such a monster and all that stuff. When that trial ended, the foreman came off the stand and said, "We totally reject the claims they made and Mr. Steinberg is a man of honor," and they voted a $44 million verdict, of which $22 million was punitive damages for what they said. Having said that, you can't take it off the record and it's still there. I have no reason not to be honest about it. You live it, you own it.

And now you're on the way back?

LS: I waited four years and now I got funded because I wanted to build the same thing again. I agreed with a production company to do a reality show, Do You Want to Be a Super Sports Agent? The reason I agreed to do it is because it would be the ethical Apprentice. I want to show people they could be conventionally successful without compromising their values.

So why was now the right time to release the book?

LS: I've been working on it for a couple of years. I went away for a while and I wanted to explain to people who I was a role model for what happened. I wanted to talk about concussions, a better way to be an agent, and I wanted to see if there was any way I could shortcut the pain of someone who was just as confused and lost as I was in this. When you're in the middle of it you can't see the future and any way out. You're only going to live one time, what life am I saving being honest for? I hope they find it helpful.

Got a favorite this Sunday?

LS: I like Seattle. It's going to be a close game, but their defense is so tough. It comes down to how well Richard Sherman and Earl Thomas can defend against Manning.

***

Daniel Kohn is a writer based in Los Angeles. He loves warm weather, English tea and 24-oz ribeye steaks.