A trampoline used to stand on the lawn of the Watts family home in Buckinghamshire, where Keith and Paula’s “funny and loving” youngest child, Zoe, would spend her days practising her routines.

Now, the trampoline has gone, and so has Zoe. Last year, at the age of 19, she killed herself in a secure mental health ward the night before she was due to be discharged.

Last week a jury of seven women and three men concluded that failings in Zoe’s care could have contributed to her death. Sitting at Beaconsfield coroners court, they listened to two weeks of evidence, much of it from the doctors and nurses who had cared for Zoe, before writing in a narrative conclusion that “risk-related incidents were inconsistently recorded and communicated”, “historical risks were not given sufficient weight”, and “communication [with Zoe and her family] was neither timely, formal, nor sensitive”.

Zoe was just a few weeks shy of her 20th birthday when she died in the Ruby Ward at the Whiteleaf Centre in Aylesbury in March 2017.

She was due to be discharged the next day, but had said she did not feel safe out of hospital and had warned her parents and her care coordinator that she would kill herself if the discharge went ahead.

Zoe’s case does not stand in isolation, but it serves to illustrate the difficulties that young people face in accessing appropriate mental health care, and how the transition from adolescent to adult services can be a huge obstacle not just for teenagers, but also for the families who are trying to support them.

At the Watts family’s cottage, Zoe’s presence — and her absence — is still keenly felt. Her trampolining medals still hang in her bedroom, and framed photographs of Zoe and her sister Hannah, with their matching long, dark hair, are dotted round the living room. In the garden, Zoe’s recovery bunny, Bella, still hops around the lawn.

In one of the flower beds, an apple tree stands tall. Zoe had tried to grow her own saplings from seed during one of her stays on an inpatient ward — one grew to a foot tall, but it died. Hannah planted the replacement tree in Zoe’s memory.

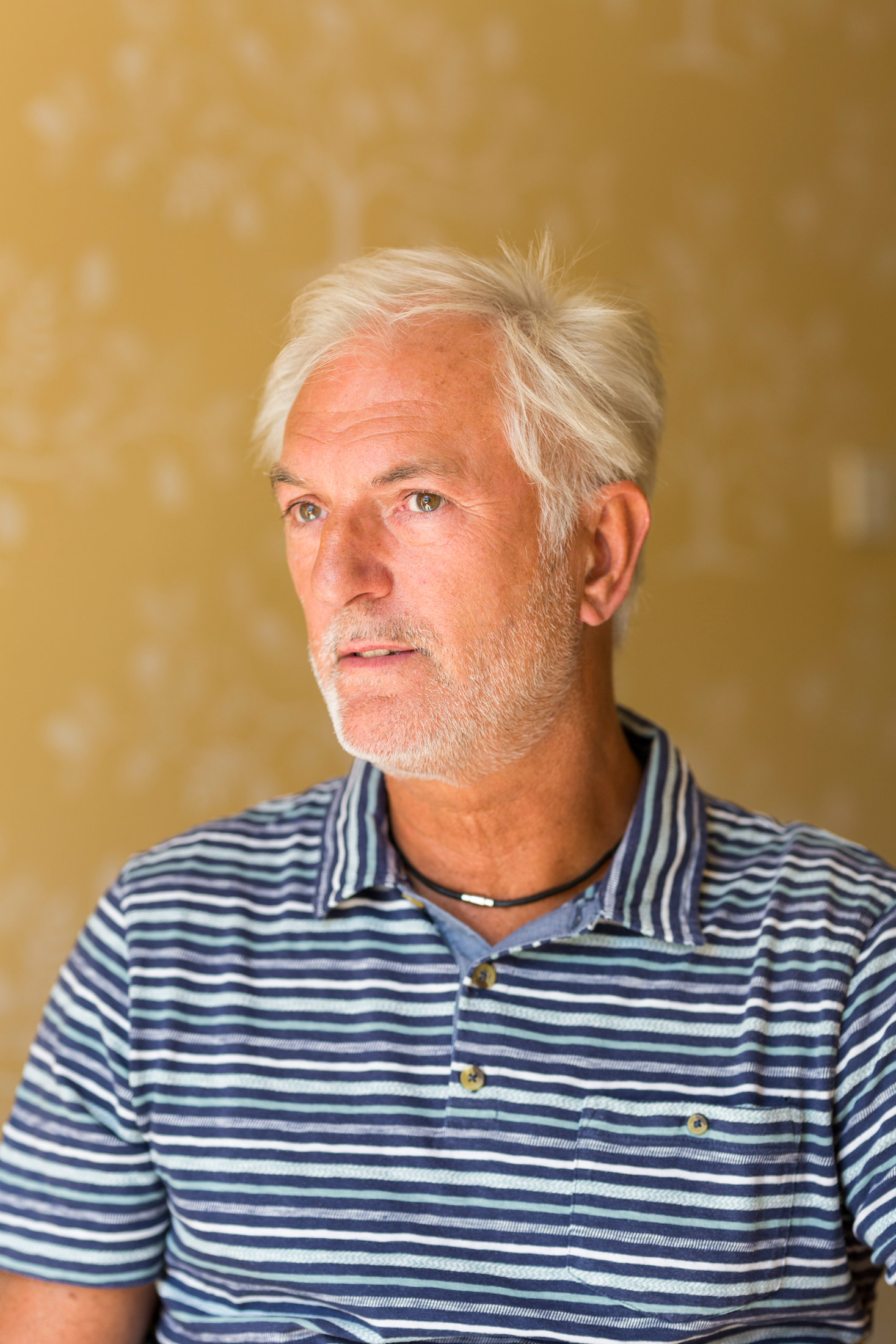

“She was a very loving girl,” says Zoe’s father, Keith Watts. “She had a wicked sense of humour.”

“She was funny and running around all the time, so much energy. Twirling round the kitchen to random songs,” Hannah, two years older than Zoe, adds. “She loved pets — that’s why we had so many.”

Zoe was born in April 1997 in High Wycombe, the youngest of three. She was bright and did well at school, and even at the height of her illness, she was studying to become a nurse. She was a talented gymnast but switched to trampolining after suffering some injuries.

“She was very gifted and very talented, very controlled; she could have gone a long way, if she hadn’t got this illness."

She excelled on the trampoline as she had at gymnastics, and had dreams of competing for her country. After just three years of training, Zoe came third in the national championships. But this competition was to be her last, as her declining mental health cut short her once-promising career.

“Right from an early age she did her gymnastics,” Keith says, “so she’d be quite often standing on her head somewhere or she’d be practising on the trampoline in the garden. She used to sing quite a lot — she had quite a nice voice as well.

“She was very gifted and very talented, very controlled; she could have gone a long way, if she hadn’t got this illness. She did lots and lots of things. Trampolining, that was her dream.

“Life was good for her. We used to have lots of lovely holidays — we went to Cuba three times. She’d go to Weymouth to her nanny and grandad’s quite a lot.”

Zoe first became ill in late 2012, and her parents began to notice changes in her behaviour. She developed rituals, insisting that the volume on the television or radio had to be at an even number and counting out cereal pieces so that she did not eat an odd number.

By January 2013, Zoe’s obsessive-compulsive behaviour developed into a more serious problem: She stopped eating and began to lose weight very quickly. Keith and Paula took Zoe to the family GP. It was the start of a long battle to get their daughter the help she needed — a fight that they would ultimately lose.

Zoe was referred to child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS), where staff suggested she should be treated at home. Her parents thought she needed more than this, and with the support of their GP they used their private health insurance to secure Zoe a place at the Priory in Richmond, southwest London.

Zoe was admitted just before her 16th birthday. She spent around seven months in the Priory, partly funded privately and partly by the NHS. By the time she was discharged in November, Zoe was almost back to normal and went back to school.

However, after Christmas, she became unwell again. She began eating less, and for the first time she started self-harming. After contacting their MP, Dominic Grieve, and writing to the CEO of Oxford Health NHS Trust, her parents managed to get Zoe a bed in mid-2014 in the Highfield Unit, an adolescent inpatient facility in Oxford.

After 10 months in the unit, Zoe was her approaching her 18th birthday, and her parents knew she would not be able to stay at Highfield. She remained there until May of the same year, a few weeks after her birthday, while she waited for a bed and was then transferred to the Ruby Ward.

Her parents thought it was the wrong place for her.

"They do try to prepare the young adult to becoming an adult on the services, but I don’t think anything can prepare you."

“The Ruby Ward is a unit where they put all kinds of illnesses in one place,” Keith says. “You could be bipolar, you could be schizophrenic, you could be a drug addict, you could be an alcoholic — you could be anything across the spectrum of mental health, all in one place.

“Putting all of these people with all of these different psychological issues in one place, it tends to emulate amongst them. They start to pick up habits from other patients with different issues, and so the outward effect of that is it actually masks their real problem.”

Paula adds: “She went from having a room where there was televisions, there was a pool table, there was ping-pong, there were games — all this — to this unit on the Ruby Ward, where it was book club, gardening club... It was just such a drastic change. It was awful.”

“They do try to do a transition,” Paula continues. “They do try to prepare the young adult to becoming an adult on the services, but I don’t think anything can prepare you for how different adult services is to CAMHS.

“They can stay in Highfield until the day they turn 18 and then they’re meant to transfer out, but there wasn’t a bed anywhere other than the Ruby Ward. We were desperately trying to find a facility. They’d given us a list of facilities that Zoe had access to, and the one they were trying to send her to was over 200 miles away.”

Once Zoe turned 18, her parents were shut out of decisions relating to her care.

“CAMHS rely on the family,” Paula says, “but then when they go to adult mental health they’re told that they have to take responsibility. But all through the CAMHS time, you’re told as parents that you’re to do everything for them, and then suddenly the child, who is now an adult, has to take that responsibility. It’s overnight as well.”

"You’re told as parents that you’re to do everything for them, and then suddenly the child, who is now an adult, has to take that responsibility."

“They suddenly turn 18 and everything’s meant to be their responsibility,” Keith adds. “When she’s 17 and nine tenths we can make decisions for her, we can talk to her physicians, talk to her doctors, and make decisions for her.

“Overnight that changes, when she becomes 18 and we’re no longer privy to any information that’s going on with her treatment or her health, and that now is all discussed locally with her, and until you get a written consent from your child they will not share any information with you.”

Zoe had a very close bond with her parents, particularly her mother, which medical staff were unhappy with, her parents say.

“As a family it’s very hard,” Paula tells BuzzFeed News, “because Zoe came from the background that she came. I would take her to training, that was six days a week, and then we would compete at weekends. South Shields, Liverpool — when you’re competing nationally it’s not locally. We had a very strong bond, which the NHS didn’t like when it came to adult services.”

“They said some things that were very painful,” Keith adds.

While on the Ruby Ward, Zoe continued to self-harm and tried to escape several times. She was restrained by staff on a number of occasions, and during one episode of restraint, her back was damaged — yet staff did not immediately seek treatment for her, and Zoe rang her parents crying in pain.

“After five days of Zoe being in excruciating pain on the Ruby Ward we really kicked up a real stink,” Keith says, “as they wouldn’t take her for an X-ray.” After her parents intervened, Zoe went to Stoke Mandeville Hospital for a scan. “They found that they’d slipped a disc and it was crushing the spinal cord,” Keith says. “They sent her straight away in an ambulance to Oxford to have the operation done.”

Zoe’s parents had hoped that she could be readmitted to the Priory, where she had done well, but in the meantime her diagnosis had changed, and she was said to have an emerging personality disorder. Her parents still dispute this diagnosis and think that it stood in the way of her getting the help she needed.

She was admitted to the Cygnet Hospital in Ealing, west London, which her parents said was a much better fit for Zoe than the Ruby Ward. The centre specialised in both eating disorders and personality disorders, and Zoe was admitted to a unit for the latter.

“Because of her diagnosis by CAMHS we couldn’t get her into the anorexic side,” Keith says. “We had to get her into the PD side, and from our point of view that was wrong, and she knew that was wrong as well.”

“Even her consultant there disagreed that she [had] borderline personality disorder,” Paula adds. “He thought she had psychosis and OCD and anorexia.”

Zoe improved while at the Cygnet and came home for Christmas. By early 2016 she was having regular home leave and community leave, and by the summer of that year, staff began to talk about discharging her.

She started her nursing course in the autumn, and her parents said she was happy and doing well — though at this point she was on medication, including a slow-release or “depot” antipsychotic injection, was self-harming at times, and was still on a section in case of a relapse, meaning her treatment was compulsory under the Mental Health Act.

In December, Zoe’s medication was reduced and she was discharged and placed on a community treatment order (CTO), which meant she could be recalled if she stopped taking her medication.

"When she started to slip, she would slip really, really fast. It was never slow with Zoe."

“It was reduced and it was reduced too fast and too soon,” Paula says. “It was what Zoe wanted; she wanted to be off the medication, but with Zoe when she started to slip, she would slip really, really fast. It was never slow with Zoe — and we saw her slipping after the first reduction.

“They kept reducing it and we were just watching her slipping, self-harming more. She wouldn’t be able to think clearly; she was thinking with her ill side.

“She stopped taking everything. She refused the depot even though she was on a CTO enforcing that she had to take her medication, and that if she didn’t take her medication they would recall her — and they didn’t.”

“They just completely left it and it just completely spiralled out of control, with self-harm and suicidal thoughts,” Keith adds, “and all this time we were nagging away on email, saying we need a meeting, we need something done, and they were just completely ignoring us.”

Christmas that year was good, her parents say. Zoe had deteriorated, but she spent the holiday with the family and went out on New Year’s Eve. They hoped that her recent decline was just a bump in the road.

However, Zoe continued to decline, and her parents said that by February she seemed “more unwell than she had ever been”, cutting deeper when she self-harmed, and in five weeks she made seven suicide attempts.

On February 19, 2017, Zoe was sectioned again. Her parents did not want her to go back to the Ruby Ward, but there was nowhere else available, and they knew that she needed to be in hospital.

Zoe stayed on the Ruby Ward until March 3. When she was discharged she was back on medication, but she continued to self-harm and she had spoken about wanting to end her life.

After her discharge, Zoe’s self-harming escalated and she made another suicide attempt, then a second. She was readmitted to the Ruby Ward on March 16. Just four days later, staff wanted to discharge Zoe again.

She wanted to stay in hospital, telling her parents that she did not feel safe and that she felt that staff had given up on her.

“Zoe knew she was stuck in a cycle,” Paula says. “She was saying she needed to stay as an inpatient for a long period to get off the cycle. She knew that she was stuck and that she needed to break it.”

Keith says that Zoe “absolutely” wanted to get better, adding: “She knew she just needed to get off this merry-go-round and she didn’t know how to do it. She wrote several things saying ‘I can’t do this alone’ and ‘I want help’ — she was very intelligent.”

On March 22, the day before Zoe’s discharge, she had a family therapy session and said that she would definitely kill herself if she was sent home. Later that day, she told her mother of her intentions and also left a message for her care coordinator, psychiatric nurse Gladmore Maringa, to say the same.

“She texted me and said that she wasn’t going to be safe,” Paula says. “So I called her, we talked — I said that she needed to take responsibility as that’s what they’d told us to say. She tried to call Gladmore but it went to voicemail.

“She’d never told us before that she had intentions to do something — never told us. And she said, ‘This is me taking responsibility: I’m telling you I’m not safe.’ I called the ward and told them.”

“They pretty much ignored it,” Keith says.

“They said that Zoe was manipulating us,” Paula adds, “so they told her on one hand that she needed to take responsibility, so she took responsibility and told us beforehand, which she’d never done before, and they said she was manipulating.”

That evening, the ward’s modern matron, Christine Ah-thion, went home and sent an email to other members of Zoe’s treatment team, asking if all avenues of treatment had been explored and saying that she feared Zoe might leave hospital and kill herself. “Would we all feel comfortable,” she asked, if they found themselves sitting “in a coroners’ court”?

By the time she sent the email, Zoe had already made her final attempt.

Her parents received a call just after 9pm asking them to go straight away to Stoke Mandeville Hospital. Once they arrived, they were told that doctors did not know what condition Zoe’s brain was in. By the Saturday, two days later, doctors had confirmed that she was brain-dead, and her parents agreed to donate her organs in line with Zoe’s wishes.

She died on Tuesday, March 28, after the donation had taken place.

“I think there were many, many missed opportunities,” Keith says. “If you exclude the private care that we got for her, and we really fought for that as well, our opportunity with CAMHS and with community services is incredibly painful.

“The problem is, if you throw more money at the system, is it going to cure the problems? It will cure some of them. It may introduce more trained staff in certain areas. It will certainly give them the ability to have access to more private facilities.

“I think it should also give the ability to process requirements quicker — commissioning for private facilities.”

He adds: “I think some of the issues here, with the community services team and CAMHS, is money, without a doubt. They don’t have the finance or the resource to do the job properly... The staff are overstretched, the facilities overwhelmed.”

“I think there were many, many missed opportunities”

At the inquest into Zoe’s death, more than a dozen medical professionals who had been involved in her care gave evidence. The jury heard that a conflicting second opinion on Zoe’s diagnosis by a Dr Pearce had been effectively ignored by her consultant, Dr Pharoah; that Zoe’s care plan was not properly updated and was incomplete; and that incidents such as blades being found in Zoe’s room and text messages indicating suicidal intent were not recorded.

“At the moment all I want is to die,” she wrote in a text to Maringa on March 16. “But I don’t want to feel like that, I want to enjoy things but I can’t. They’ve given up on me, so why should I bother?”

Another, sent a month earlier, on February 16, read: "I feel like I'm already dead inside so it doesn't matter. I cannot live like this I'm suicidal every minute of every day, I dream about dying I cannot cope."

The inquest also heard that Zoe’s risk assessment was not updated in the days before her death; that there was a lack of a clear discharge plan; and that there was a breakdown in trust between medical professionals and Zoe’s family, who were shut out of decisions relating to her care.

The jury said in their conclusion that “more flexibility in the discharge date may have helped to alleviate Zoe’s feelings of abandonment in the days leading up to the incident”.

When they returned their verdict, vindicating what the Watts family had been saying all along, Keith says the moment was bittersweet.

“We want them to understand it from our point of view,” he says, referring to Oxford Health NHS Trust. “We want them to do something about it. It’s too late in the day as far as we’re concerned, but it will protect other families if they do it right, if they involve the family. If they try to isolate the patient from the family, they’re never going to win.

“After the verdict was called we were pretty numb, pretty hollow, because it was a long two weeks, a very painful two weeks. It was quite emotional because it kind of meant that what we’d been saying all along, for a very long time, kind of came to fruition, and it was agreed by the jury that there were lots of things that were wrong.

“But if they had got them right, things would be different today, and that’s quite upsetting.”

A spokesperson for the trust said: “Oxford Health would like to offer its deepest condolences to Zoe’s family at this very difficult time.

“The trust accepts aspects of the care we provided Zoe could have been better and we accept the conclusions reached by the jury.

“Oxford Health strives to provide appropriate individualised care and treatment to patients based on the clinical observations of a range of mental health professionals and our patients’ needs.

“However, we recognise that communication with Zoe’s family in the months prior to her death should have been better and that there could have been more flexibility around her intended discharge from the ward.

“Subsequently, there has been a significant amount of work within our adult mental health inpatient settings, which has included a review of our processes, and the recommendations from this review have already been implemented across all our wards.”

Merry Varney, who worked on the Watts family’s case for solicitors firm Leigh Day, told BuzzFeed News: “The inquest process has allowed Zoe’s family to have a better understanding of the circumstances of Zoe’s death, and the jury’s finding of multiple failings which may have contributed to Zoe’s death are a vindication of the concerns they, and Zoe, expressed before she died.

“It is imperative that the welcome steps the trust are implementing to improve care are audited and reviewed regularly to prevent more potentially avoidable deaths.

“In addition Senior Coroner [Crispin Giles] Butler noted repeatedly that the bereaved family should be at the heart of the inquest process — something which should be, but sadly isn’t, replicated across the country.”

Back at the Watts’ home, a butterfly has flown in through the open French doors, and is fluttering below the ceiling. Butterflies, Keith says, came to symbolise his daughter’s recovery. She had a butterfly tattoo on her ankle, and there is a poem about butterflies on the plaque that leans against the apple tree that Hannah planted.

A smile returns to Keith’s face as he recounts a story about Zoe’s older brother, Ashley. “Despite the fact he’s a half brother, there’s still a very close bond,” he says. “He finds it difficult. He still gets emotional.

"We’ll never forget. She’s on our minds every single day.”

“His last conversation with Zoe was when he was in Thailand — he went to Chiang Mai and he saw the elephants.” When Zoe said that she’d love to see elephants, Ashley promised to take her there, Keith says, although “of course he never had that opportunity”.

On a return trip to Chiang Mai, Ashley brought some of Zoe’s ashes with him.

“He took the ashes to the elephant sanctuary,” Keith says, “and he had the most amazing experience.”

Ashley was looking for a blossom tree overlooking the sanctuary — the perfect spot to scatter the ashes — when he saw something. “As he was going through the jungle there was this huge butterfly, beautiful butterfly, and it took him to the tree and he sprinkled the ashes,” Keith says.

The Watts family has always been incredibly close, Keith says, and they have all clearly been devastated by Zoe’s death.

“When you get married and you start growing a family, you build a structure,” he explains, “and if you take one of the important supports away from that structure, it falls over, until it finds its new level.

“And so we’ve been trying to find the new level without Zoe. We’ll never forget. She’s on our minds every single day.”

If you are feeling at risk of suicide or if you are worried about someone else call the Samaritans: 116 123 (UK) / 116 123 (ROI).

If you’re in the United States you can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).