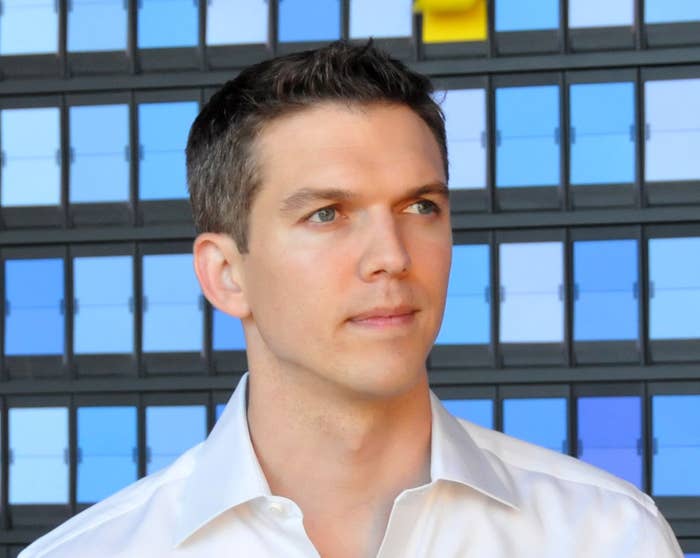

In August 2007, Matt Ivester, then a recent Duke graduate, founded Juicy Campus, an entirely anonymous online message board with pages for a handful of colleges. The site quickly grew, and so did its reputation — as a hotbed for cruel gossip and name-calling, like Mean Girls without any of the irony.

If you were an undergraduate at some college in America between that time and early 2009, when the site shut down, you were likely familiar with the site and the inane, often cruel debates that ruled it. The site's complete anonymity — you didn't even have to log in — meant students could post completely unsubstantiated rumors with no consequences. Nearly every school's page contained continuously updated threads on the "biggest slut on campus." Racism and sexism were common fixtures. The cruelty was unrelenting: here, a UConn student describes a thread where posters called her "deserving of being beaten by [her] boyfriend." And here, the story of a Yale student whose appearance in a pornographic video was posted for the whole internet to see.

Regularly, it turned into a hate-spewing witch hunt of sorts. Questions like which fraternity members were secretly closeted, or which girls had gained the most weight over winter break, were posed, and the anonymous responses would pour in. My name showed up once in a post that, relatively speaking, was pretty tame, and I still remember how awful it felt, just to know some virtual stranger cared enough to bother to make you feel bad.

All in all, Juicy Campus was very, very mean.

It may be a surprise, then, that Ivester is now a full-time advocate for niceness on the internet. In 2011, he published a book called lol...OMG! about cyberbullying and "digital citizenship." And last month, he started Kindr, the world's first "kindness app," with which users send their friends compliments and receive gushy, feel-good headlines from The Huffington Post's Good News vertical.

"It certainly all starts with having run Juicy Campus, which was such a place of meanness," Ivester said. "It was really a negative experience for a lot of people, including myself. When I started it, I didn't realize kind of how fundamentally different online gossip is from offline gossip. So when the site shut down and I had some time to reflect on it, I realized that I had been dealing with issues of cyberbullying before cyberbullying was even a term in our vernacular."

In 2008, Ivester made some attempts to salvage the Juicy Campus reputation, urging users to be a little less cruel.

"I wish in retrospect that I had been able to shut it down and say I don't want to do this anymore. I think I was naive in thinking that I would be able to turn the tide. I posted a letter called Hate Isn't Juicy, trying to encourage people to think about what's the difference between what's entertaining and just being mean spirited. I was always hopeful that over time, we'd be able to change the tone of a site," he said.

It was a bargain that, unsurprisingly, didn't work.

"When I would read in the customer service emails that people would write in, asking for stuff to be removed, it gets to you when you realize that the site you thought would be kind of fun is really more hurtful than interesting or helpful. From an emotional standpoint, I'm a good nice person and I found myself in this position where I was running this company that was a cyberbullying platform. That didn't feel good."

Eventually, crediting a lack of revenue, Juicy Campus shut down in early February 2009. The following year, Ivester went to Stanford Business School, and over the summer between his first and second years, he wrote his anti-cyberbullying book.

Some Juicy Campus copycats popped up — first College ACB (Anonymous Communication Board), and later, Collegiate ACB , which is still around — but none managed to capture the novelty (or cruelty) of Juicy Campus.

Today, Ivester is convinced that teenagers, college kids, and other people who spend their days online "are craving positivity" and that "they're sick of the meanness and they're rebelling against it."

"Today as I look at Juicy Campus, it's so not the kind of business I would want to be a part of anymore," Ivester said.

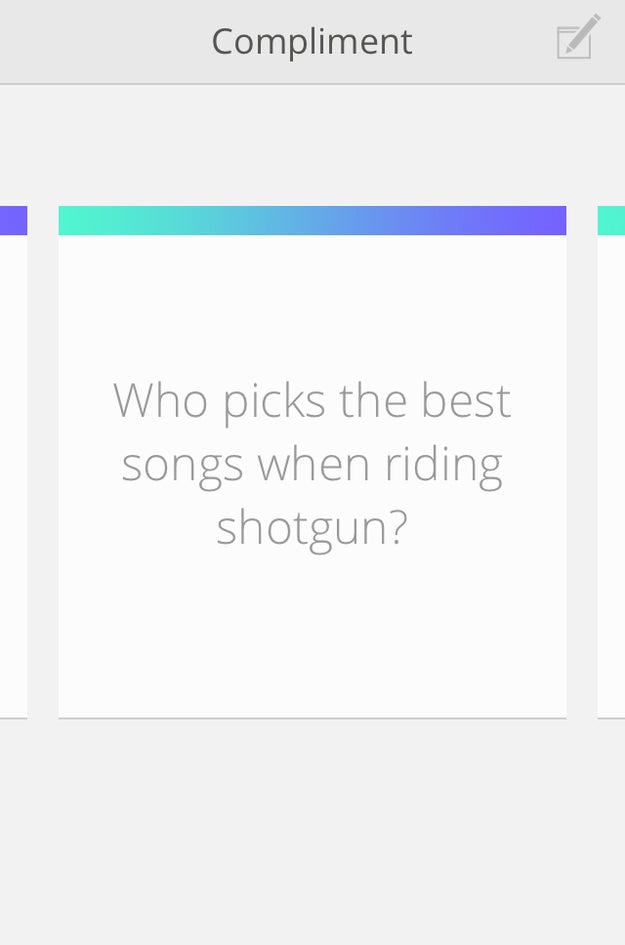

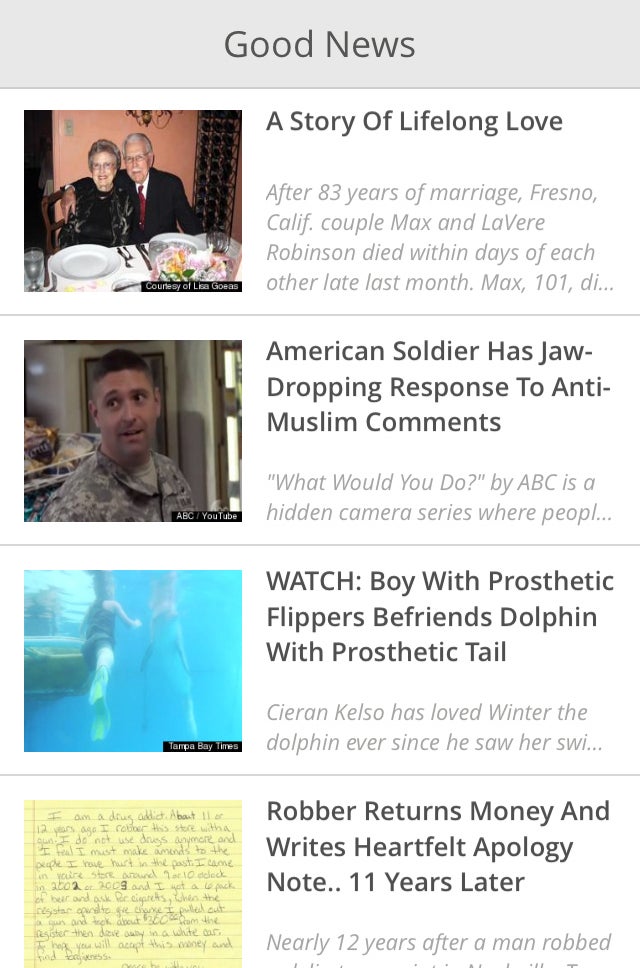

So Ivester's answer is Kindr, an app he and a co-founder launched Oct. 3 that lets users send friends Hallmark card–like "compliments" such as, "You make me as happy as Friday makes Rebecca Black." The second most popular compliment, after "You're awesome!" is "You remind me of Frosted Flakes because you're grrrrrrrreat!" The app also sends users push notifications with headlines like, "WATCH: Homeless Family's Incredible Makeover Will Put You In The Giving Spirit."

Not unlike Juicy Campus, Kindr doesn't yet have a clear revenue stream. "At the moment there's not one," Ivester said, regarding the app's business plan. "My co-founder and I just started it as a fun project. We got into it way more than we ever expected," he said.

"To keep the lights on, we're going to have to figure out some kind of business model or find donors. That's definitely the next step."

Ivester isn't the first proprietor of a platform for internet meanness to seek a kinder path. Perez Hilton has become an anti-bullying advocate and has apologized to some of his celebrity targets on national television. In a New York Times profile last year that called him "repentant," he talked about "no longer [being] toxic to the world" and tweeting inspirational quotes.

But all this says more about how the internet has changed over the past few years than it does about website founders looking for a shot at redemption.

Today, snarky blogs have lost most of their traffic to sites like Upworthy that peddle in shareable tear-jerkiness and humanitarian feel-good vibes — the kind of "Good News" stories Kindr alerts you to. And with social media powering so much web traffic, hiding out unnamed feels unusual. Anonymous forums like 4chan are mostly considered fringe, and if you're getting attention for being anonymous on Twitter, it's more likely you're a weird art project than a cruel gossip machine.

"It was six years ago," Ivester said. "It was a different time on the internet when people didn't understand the psychology of anonymity and all the complex issues that surrounded Juicy Campus — the concept of free speech versus bullying. It was complicated, and in retrospect, I wish I had never started it in the first place."