Bruce Yang has spent a considerable amount of time promoting his new ephemeral drinking app called Sobrr since its launch this past June. One of his target audiences? High school students.

Or at least it was.

During an hour long interview with Yang over Skype last week, I pressed him about the possible risks of promoting his app to younger users with the expectation that Yang had thought deeply about his strategy. Instead, to my surprise, Yang told me he changed his mind.

"I didn't think that much before I talked to you — after talking to you I have to think about promoting it to high schoolers," Yang, a U.C. Berkley graduate, told me.

The conversation and its end result offered a fascinating look into the fluid dynamics and false starts of creating and developing an application in 2014.

Yang certainly didn't create the app with only high school students in his crosshairs.

In September of 2013, Yang was about to get married when, like so many men before him, he journeyed to Vegas to commemorate his impending nuptials. But he quickly learned that in this age of social media what happens in Vegas...typically ends up on somebody's newsfeed.

"We wanted to make sure nothing stupid happened at the wedding," Yang said. "We couldn't remember a lot of things but we removed everything from our WhatsApp [and] on Facebook, since everything has a record on social networks. The people we met [that night], we removed these people from our contact list."

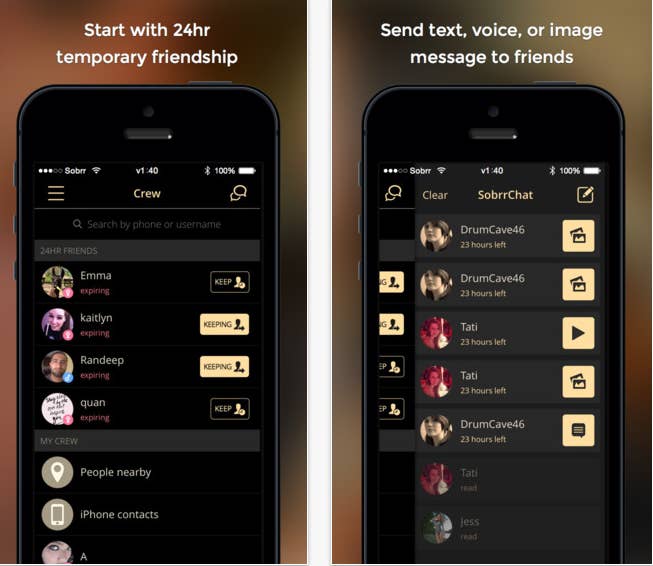

It was this scurry to cover his tracks that prompted Yang to create Sobrr. On Sobrr, everything (even the friendships a user might form on a night like Yang's) expires after 24 hours. The app combines aspects of Tinder — such as a geolocation-based friend finder and photos you can swipe right to "cheer" or left to "pass" — and SnapChat.

Upon downloading and signing into the app, users come across a photo feed with a similar feel to Tinder's. But these photos are not necessarily being posted by people within your networks, nor are they of someone you "matched with" like on Tinder. Instead, what you're seeing are photos from strangers, who happen to be Sobrr users within a close proximity to you. Users can then swipe right, swipe left, or tap this stranger's icon and add him or her as a friend. If the stranger accepts your request, you'll have 24 hours to message and otherwise cultivate your friendship. Before the friendship expires, users have the option to "keep" that friend and add them to their permanent "crew." No matter what, though, the interactions between new friends, your existing Facebook friends, and iPhone contacts will disappear after one day.

Yang is currently looking into expanding his market to China, where he says they'll be targeting the English-speaking population, or what he refers to as the "knowledge class." But in the United States Yang says he sees two target audiences: college students and high school students.

"When [college students] go to [a] college town, it's [the] first time they start to enjoy the freedom without their parents' control," Yang said. "They like to go to parties, they like to enjoy the moment, but they really don't want their parents or friends to know what they did last night. So we wanted to promote this for college students and partygoers."

Though he argues it's not the main premise of the app, Yang said the app can be used to "pick up a girl or guy" or "hook up," arguing, "it's a basic human need."

After helping facilitate college hookups, Yang told me Sobrr would set its sights on high school students, which felt to me, if not flat-out wrong, at least like a potential optics disaster.

"They want to be different because they've started becoming young adults, but the problem right now is that they have to stick with their parents," Yang said. "Parents are really strict with high school students. They say, 'You shouldn't have a relationship otherwise you won't get into [a] good college.' If I'm a high schooler, whatever I post online, it only lasts 24 hours. [Parents] can't see anything in my history, every message is gone. As I heard a lot of high schoolers [say], they have to delete every message they've sent because their parents want to check their messages. Sobrr wants to help them hide their small secrets."

Aside from the obvious issues that helping adolescents hide things from their parents poses, the inspiration for, the promotion of, and the name of the app allude to drunken nights and the need to hide the resulting social interactions the next day. I asked Yang if he worried about running the risk of promoting underage drinking by targeting high school students.

"We're not promoting the drinking culture for the high schooler," he answered. "The fact is, when I look at how many people [use] Sobrr, most times it's just life moments [or] very random things, just a cat photo. Different people use Sobrr differently," he said.

But so far Yang's promotional efforts — which include press, the company's blog, and promotional videos — focus largely on how his wild night in Vegas led him to contemplate creating an app like Sobrr. Additionally, Yang told me that Sobrr plans to target college students and partygoers in ostensibly the same geographic location as the high school students he plans to target, which will lead to an overlap between users looking to hook up and the (presumably) under-18 crowd.

"It's a very empty, light relationship," Yang said of the app's 24-hour friend feature. "You can meet new friends without worrying about what I post today. If you know that the friendship will expire, you're more willing to give it a try."

It's a feature that, while potentially appealing to college students arriving on a new campus, could expose younger users to a host of risks.

"Although [the app operates on] geographical proximity, one thing which we do is we don't really have geographical barriers," Yang explained in an attempt to rebut that point. "It's just how many users are around you. If I'm in a high school and there are 500 people using Sobrr, I won't see other people using Sobrr, just those 500."

But this logic, I posed to Yang, is only sound when operating under the premise that high school students stay and only use the app within the bounds of their own high school.

"Yes, I agree with that fact," Yang said. And then, to my surprise, he immediately changed his pitch. "I think after this conversation, we are not going to target high schoolers anymore."

This is not say that not targeting high school students will stop high school-age teens from using the app. Or that teens using this app will engage in high-risk drunken behavior simply by using Sobrr. But the risks involved in launching a campaign that promotes specifically to high schoolers is worth considering. Also worth considering: how much critical thought goes into the social consequences of the tech products that are targeted toward minors.