American Apparel CEO Dov Charney was slapping himself in the face. After every third or fourth slap, he fixed his eyes on mine, pointed his finger at me, and yelled, "This is what you did to me!" This was the first time Charney and I had met.

In 2009, during my sophomore year in college, I got a job at an American Apparel store in Chicago. That year Charney was a finalist for Time's "Most Influential People in the World." American Apparel had received accolades for being one of few clothing manufacturers that held decent labor standards in an infamously abusive industry. Through the business, Charney had also supported progressive causes like immigration reform, environmentalism, and gay rights.

At the same time, the company had more than its share of critics. Many took issue with Charney's hypersexualized advertising, earning him a reputation as a chauvinist. Countless stories of his exhibitionism and inappropriate sexual conduct with employees abounded, and there was a long history of lawsuits against Charney himself and the company for sexual harassment and abuse.

When I was hired, Charney was under fire for his new store policies. It was well-known that before hiring any employee, managers had to send photos of job applicants to the L.A. headquarters for approval, but the company was taking this further. An employee tipster told Gawker about the "class photo," when headquarters demanded a photo of all staff on duty within five minutes. The employee claimed that executives pressured managers to fire their employees based on the class photo, calling it an effort to weed out "uglies." Charney said they were judging fashion sense, but critics, including many employees, said it amounted to "beauty profiling."

I was one of those employees. Hearing stories of abrupt firings and complaints from female employees who felt unfairly targeted, I spoke out online. I harshly denounced the company's policies on an internal forum meant for work discussion. I also went public with my critique in the comments section of a Gothamist post. Identifying myself as an employee, I wrote that the post "doesn't even grasp the magnitude of the company's dehumanizing policies and actions" and that "I have serious issues with the company's ethics — especially when you compare them to the way the company tries to present itself as 'progressive' and 'ethical.'"

The comment Timm left on the Gothamist post:

While folding clothes in the stockroom back at work the next day, I received a phone call.

"Hi, Jonathan, it's Dov."

He was calling, he said, because he saw what I had written online. He accused me of damaging the company. Yelling into the phone, he said that he was tightening the dress code only because he saw employees who weren't representing his brand well. It was about style, he said, not looks, and he hadn't fired anyone based on photos. I'm as good as gone, I thought, so I might as well speak my piece. I said I didn't believe him, and I saw it as part of a pattern of unfair policies that created an uncomfortable working environment, especially for women.

Our conversation lasted more than an hour, with Charney ending it by saying that although he respected my boldness, I had him wrong. "You think I'm some corporate fat cat, but I'm over here eating out of a can, OK?" he quipped. "I'm just trying to run a good company." If I saw for myself how he worked, he said more than once, I would understand.

"I'll tell you what, I'm going to fly you to the factory. I'll pay for your flight. I'll pay for your hotel," said Charney, giving me his phone number in the process. "Just do one thing for me, and take down that comment."

My idealism was no match for the intrigue. I hadn't changed my mind about his policies, but I had been dazzled. While it was easy to paint Charney as a soulless profiteer from behind a computer screen, it was much harder to do so with him on the other end of the phone. His excitement is contagious. Even when he says ridiculous things, you can see that he believes them, and you almost want to believe them too. He talks a mile a minute, pausing only after making a bold statement and punctuating it with an expansive hand gesture and a big smile.

Charney persuaded me that his request to take down my Gothamist comment was fair, but since that was out of my control, I did the next best thing: I went online and backpedaled hard. "I'd like to take back what I said and I am going to do more research to obtain accurate information about this issue," I wrote, "suspending my judgment for now."

Late one night a few weeks after our initial conversation, Charney called me again and, without even saying hello, asked, "Can you get on a plane tomorrow morning?"

Arriving outside of the sprawling set of pink and tan rectangular buildings that make up the iconic American Apparel headquarters the next afternoon, I was greeted not by an assistant with a clipboard but by Charney himself. Wearing a ruffled white polo and blue-and-white striped pants that he designed, Charney shook my hand and told me to wait while he and his assistants pulled a couple of prototype styles out of a trunk to examine. Once he was done, he shifted his attention to me and snapped into his dramatic display, slapping himself as a symbol of how I had wronged him.

"Now you're going to see what we're all about," he said, visibly shaken, "and how wrong you are."

Inside the factory, Charney passed me off to an assistant for a tour. The place was a marvel — a gigantic, bustling factory full of predominately Latino workers, sewing machines, bright fabrics, natural sunlight, and a pleasant breeze. Signs pointed me to the cafeteria, where employees ate subsidized meals. In a room down the hall, workers got free professional massages every three weeks. By any standard, this wasn't a bad gig. By the apparel industry's standards, it was paradise.

But I wasn't there because of an argument about the factory. While I enjoyed the spectacle, it wasn't clear what Charney wanted me to take away from all this. Had he flown me out just to dazzle me with his factory?

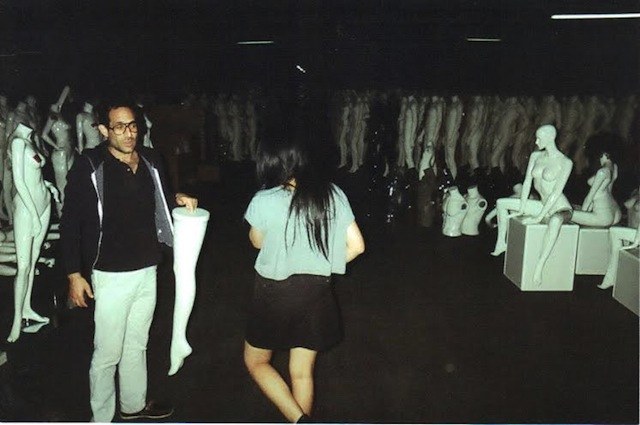

I spent the next two days milling about the premises, downtown L.A., and the luxury hotel room that Charney provided for me. At headquarters one day, I sat in on a meeting with Charney and some of his younger associates. In his rapid-fire speech, he darted from idea to idea, mostly revolving around creativity and marketing. At one point, in what seemed to be a non sequitur, he unleashed another one of his signature bold statements. "There's nothing more dangerous than a pacifist on a rampage," he said as he grinned and gave me a wink. One evening, he drove me and two young, pretty associates to a dark warehouse filled with nothing but rows of naked mannequins as far as the eye could see for a reason that wasn't immediately apparent.

My visit continued without any schedule or plans. Charney set no deadline, saying only, "There's more for you to see." After a few days of freedom — or limbo, depending on your outlook — I boarded a flight back to Chicago.

A year after my encounter with Charney, the Los Angeles office of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission found that American Apparel had discriminated against women, as a class, on the basis of their gender by subjecting them to sexual harassment. Last week, Charney was fired from the company he founded after an internal investigation led by his handpicked board of directors found new details of misconduct.

In Charney's termination letter, the board showed that he awarded large severance packages to employees, without consulting them, to protect himself from legal liability, and that American Apparel's employment practices liability insurance costs more than doubled as a result of his behavior.

Even though I wasn't a sexual target, I experienced Charney's seductive charm firsthand. His energy, optimism, and power muzzled my critiques and left me temporarily ambivalent. Being around him disarmed me.

Perhaps I should have just slapped myself instead.

An American Apparel representative declined to comment for this post.