For a long time, my favorite article of clothing was a vintage Washington Redskins shirt that I bought in a New York City thrift shop 10 years ago. It is good in every way a T-shirt can be good. It is soft and color-faded to the point that I can hardly believe it was once manufactured and purchased new; I like to imagine the shirt materializing fully mature in some circa-1986 Capitol Hill dive, lightly drunk on Schlitz, smelling like Brut and cue chalk, waiting to be worn. It's historical. It's cool. Also, my shoulders look good in it.

Because the shirt is so well-loved, I can wear it outside of the Washington area, where I'm from, without looking to non-natives like some D.C.-pride cretin who spends a lot of money in the Redskins store. At the same time, it's a killer icebreaker with D.C. people in New York, where I live now. You're from D.C.? I'm from D.C.! Let's talk jadedly. Sometimes, at a bar or a party, a dude will come up to me, eyes narrowed, gesture at the shirt, and ask if I'm actually from D.C. — y'know, a 'Skins fan for real. For reasons that feel obvious, people who were actually born and raised in the D.C. area are hypersensitive to carpetbaggery. I have to confess that I take a lot of pleasure in winning this conversation. "Yes," I reply, "and I've been a fan my whole life." It's only a T-shirt, but it lets me claim my D.C. identity with either fashionable quotation marks or indignant authenticity, as needed. Basically, it was worth 15 bucks.

I haven't really worn the shirt for the past few months, because, of course, wearing a Washington Redskins T-shirt right now is an argument and an argument waiting to happen. But a few weeks ago, running late for breakfast with my parents — who were visiting from Bethesda, the Maryland suburb just over the D.C. border where I'm from — I put it on without thinking and tripped out the door.

"You had better shrink-wrap that thing," my stepdad said, pointing a bacon-loaded fork at my chest, "and put it in storage somewhere."

Henry is a bona fide D.C. native, born and raised in Mount Pleasant and then Silver Spring, and except for college he has lived his entire life in the area. My mother married him in 1990, when I was 5, two years after my father died. He's an idiosyncratic but committed Redskins fan, and football was the first thing we bonded over. Every fall Sunday we'd watch the way persnickety locals do, with the television muted and the radio announcers — Sonny Jurgenson, Sam Huff, and Frank Herzog — turned up loud. In 1991, the Redskins went 14-2, and crushed the Bills in Super Bowl XXVI. I watched the game at a party thrown by one of Henry's friends from his JCC volleyball league. I remember sitting cross-legged inches away from the television, hands caked in Dorito dust, watching a Canadian named Mark Rypien briefly be the greatest quarterback in the world. It's one of the best memories of my childhood, because it felt at the time like the universe was compensating me in a tangible way for being a kid with a dead dad.

The Redskins' fan base drains from reservoirs of patience yet unfathomed, and Henry and I were no exceptions. For the past 15 years, even as the team name became synonymous with incompetent ownership, management, coaching, and play, we kept watching, and watching together whenever we could. We endured Gus Frerrote, Dana Stubblefield, Deion Sanders, Dan Turk, Adam Archuleta, Albert Haynesworth. And though I grew less and less attached to the outcome of any given game — Steve Spurrier will do that to you — it was still a comfort to know that I could call home any given Monday and talk to Henry about what had happened the day before. It was a comfort that the first thing my stepdad shared with me, when the fact of our relationship was new and frightening, endured.

That's why, even though I know Henry, like me, thinks the word "Redskins" is a slur and that the name should be replaced, I found myself mildly stunned by his remark last month. The Redskins, despicable name and all, have been a constant in my life since the turmoil of my early childhood. To hear the man with whom I most closely associate that stability speak of its imminent change felt, if not quite bad, then definitely weird.

I've talked to a lot of people — progressive people — from the D.C. area who share a similar, uncomfortable ambivalence. For obvious reasons, the conversation about the name doesn't accommodate the feelings of people who both want the name to change and who can't help but feel something like melancholy at the prospect. It's tempting, and not wrong, to dismiss this perspective as privilege, or the false consciousness of sports fans with nothing better to care about. But I think the feelings involved are more complex and maybe more sympathetic than that. And I think they say something specifically about Washington and Washingtonians.

As much as the Redskins have been a constant in my life, they've been a constant in the life of a city that is by its nature transitory and divided. And I don't just mean that the city is divided by politics: D.C. is liminal in so many other ways, a stepchild of a place. It has no federal representation. It has had an epically corrupt local government. It's somewhere between Northern and Southern; between white and black; between provincial and international; between the suburbs and the city limits. Instead of producing a polyglot culture out of these tensions, D.C. too often feels like a place where people don't really talk to or learn from each other. To take just the most striking division in the city, you can walk down a few of the main barhopping streets on a Saturday night in the District and see equal numbers of black and white people. And then you can watch white people walk into white-people bars and black people walk into black-people bars, alternating like piano keys. It's one of the most segregated metro areas in the nation, and when you're there you feel it deeply.

For much of their history, the Redskins were a symbol of that segregation. Washington was the last professional football team to integrate, because their owner, George Marshall, was the Donald Sterling of his day, and then some. Marshall was such a committed racist that he stipulated specifically the charitable foundation started posthumously with the holdings of his estate could not donate any money whatsoever to causes supporting integration. Suspicion and even outright antipathy toward the Redskins persisted within the metro-area black community long after Marshall died, in 1969. One popular local theory (while debunked by Washington City Paper) holds that the reason for the glut of Cowboys fans in the District is that the explosion of the black population in D.C. coincided with the last, and most public, years of Redskins segregation.

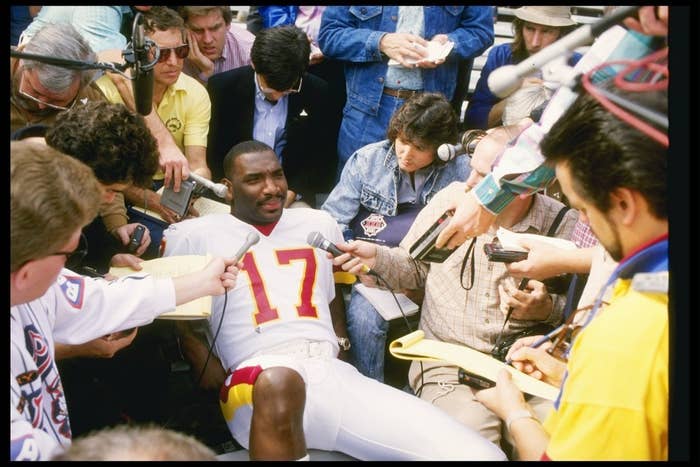

And yet despite their past, the Redskins may today be the only force in the city capable of generating good feelings powerful enough to make locals put aside the divisions caused by the very history the team once embodied. In 1988, when the Redskins won the Super Bowl behind a legendary performance from Doug Williams — the first starting black quarterback to win an NFL championship — D.C., jubilant, enjoyed a period of genuine fellow feeling across races not totally unlike 20 years later, when the nation elected its first black president. Courtland Milloy wrote in the Post on the mood in the capital after the game:

The event was the Super Bowl; but one week later it is the image of Washington as a more perfect union -- where blacks and whites hugged each other, where immigrants felt at home, where city dwellers and suburbanites joined as one -- that is just as precious as the game itself.

Look at the replays on your VCRs, check out the fans in the stands after the final gun. Who are those people locked in loving embrace? Strangers -- in black and white. Look at our team. Big, white dudes who, if dressed in overalls, would seem right at home in Forsyth County, Ga. are kissing big, black dudes who, if dressed in leather, would seem right at home on the South Side of Chicago…

Doug Williams, Timmy Smith -- let me tell you, brothers, it would have taken 10 times more shrinks and social workers than we already have working overtime for the next 10 years to come anywhere near what you and your teammates have done for us.

And, frankly, given the increasing polarization of the races here, to say nothing of the ever-widening class split, I don't think we could have afforded to wait that long.

Talk about being right on time. You Redskins gave this city just what it needed. We needed to smooth over those artificial barriers that separate the District from our neighbors in Maryland and Virginia. During the Redskins' victory parade, suburbanites came to town acting like homefolk, not just commuters.

Let's also face the fact that Washington has a big racial problem. We needed a dose of racial progress bad...

In a town where many people have high hopes of one day seeing the "first black president of the United States," having a winning black Super Bowl quarterback no doubt helps keep the dream alive.

One of the many ironies of the name controversy is the Washington area's independently fraught relationship with the word "native." Depending on context, the phrases "D.C. native" and "native Washingtonian" can carry totally opposing subtexts. Spoken admiringly, they mean: someone who stayed. Spoken disparagingly, they mean: someone who stayed. After Super Bowl XXII, Julie Rovner (also in the Post) wrote about the special meaning the victory had for D.C. natives, who must abide with grace the judgment, and perhaps relatedly the out-of-town sports allegiances of their friends, neighbors, and co-workers:

There is one thing we have, though, and that's the Redskins. Besides traffic jams, it's practically the only thing that natives of D.C., Maryland and Virginia have in common. As any local parent can attest, every area schoolchild knows the words to "Hail to the Redskins" before he or she can do the multiplication tables, and most recognize Sonny Jurgensen at an earlier age than George Washington.

The team also provides one of the few aspects of continuity in a town noted for its transience…The Redskins are also the main thing that separates those of us who live here from those who reside here simply because this is where their job is. And we all know them…They're the ones who create little shrines on their desks to their home-town (read: real) sports teams when one of them wins a championship of one sort or another.

What a good Redskins team has historically meant to Washingtonians is an acknowledgement that ours is a place as real and as worthy as any; not simply a one-industry town full of transient hacks, or else the ever-recovering murder capital, or else the ever-whitening chocolate city, or else whatever racially toxic narrative is nearest at hand. A good Redskins team has been a rare — perhaps unique — form of positive national representation. Such is the deepest and saddest irony of our football team's wildly racist name: Our football team may be responsible for more shared pride between whites and blacks in D.C. over the past 35 years than any other area institution.

To me, the worst thing about the 15 years of Daniel Snyder's intransigent, petty, and historically incompetent ownership has been the destruction of a rare beacon of common hope among metro Washington residents. To many of us, the name "controversy" is simply an exclamation point on a disastrous sentence.

The loudest voices clamoring for the name change have focused on the intrinsic offensiveness of the word, without appealing at all to the civic pride of Washingtonians. In my opinion, that has been a mistake. As long as the debate focuses on relative degrees of offense, it plays directly into the hands of Snyder, Roger Goodell, and the rest of the rich white goons who want to keep the name, and who can reliably dig up dubious talking heads and even more dubious data to defend their "tradition." It also allows Snyder to falsely identify the name itself with D.C. pride, and to frame the conflict as a struggle between Washingtonians and politically correct carpetbaggers. In the dynamics of this debate, Snyder has endless ammunition. Frankly, it's fueled by the spectacle of a congressional petition about the name of the beloved team of a city with no congressional representation. And given the lack of concern — to put it mildly — American politicians show for the abject standards of Native life in this country, such action smacks of the symbolic racial politics at which America excels and by which it always sets itself up for real-world disappointment.

Is the word "Redskin" offensive? Obviously, outrageously, indefensibly, unquestionably. So here are some actual questions that must be answered. Do Washingtonians want a team they can be proud of in every aspect of its constitution? Should not the name of a team that has been at times a force for racial harmony, a team which today boasts a black quarterback who is the pride of the city, bear a name worthy of its accomplishments? Maybe most importantly, can we make the story of the name change not past versus future, not racist versus progressive, but shame versus pride?

I think we can. Because I think Washingtonians are hungry for something unifying, something to be proud of. So here is what I'm going to do.

I hereby renounce my Redskins fandom, until the owner of the franchise changes its name to something that Washingtonians can be proud of.

I accept any and all solicitations from the other teams in the National Football League for the addition of my fandom, with a few exceptions. Because of my history as a Redskins fan, I cannot root for the Cowboys. Because I don't want to go through this again in 10 years, I cannot root for the Chiefs. Also, I am not going to become a Jaguars fan, because I'm almost 30 and I'd like to see my team win a Super Bowl before I die.

I'm calling on my fellow fans to join me. Because what I've realized is that the name we call our football team isn't worthy of the profoundly positive effect that our football team has had on my life and on the life of the city. It isn't worthy of representing a group of people who for so many reasons lack representation. It isn't worthy of my bond with my stepfather. And even if it feels as comfortable as a second skin, it isn't worthy of a foot on my chest.