It's a late afternoon in July, and already the sky above Lake Superior is mostly dark with storm clouds. I'm on a boat near the Minnesota–Canada border, and despite what I thought was a fairly clear instance of foreshadowing — turning on the radio only to hear the digitized-sounding woman on the other end say, "And here are the hazardous weather conditions for Lake Superior…" before cutting out into crackling static — we steer out from the bluff-edged safety of Tee Harbor and onto the gusty lake.It's not the type of weather most boaters are in a rush to steer into, but we're on a deadline. There's only one day left of the trip I'm on with Ken Merryman, Jerry Eliason, and Kraig Smith — three Great Lakes shipwreck hunters who are hoping to find a sunken ship they've been searching for since 2005.This ship has been missing since June 20, 1953, when weather conditions in Thunder Bay, a Canadian port on Lake Superior's north shore, were similarly ominous. A dense fog hung over the lake that day, and wind gusts reached 55mph. The lake freighter SS Scotiadoc, 416 feet long, carrying 239,000 bushels of wheat and 29 passengers, departed from shore early in the evening. Just after 6:30 p.m., after colliding with another freighter called the Burlington, it sank.The Burlington carried the wreck's survivors (all but one of the Scotiadoc's passengers) back to Thunder Bay. The Scotiadoc was witnessed just post-collision, by Captain Mitchell of the Keewatin, at 6:49 p.m. But reports varied on exactly how many miles off Trowbridge Island the ship sank, and ever since, the wreck's specific location has remained unknown.They won't tell me why, or how, but the three men — who, 30-odd years after starting this permanent quest, to find ship after ship after ship, are now approaching retirement age — aboard this bobbing boat with me are sure they'll be the ones to find it.

It's hard to hear the phrase "shipwreck hunting" and not picture something like Ariel singing to a handful of spoons in The Little Mermaid. Maybe for you it's The Goonies, or, perhaps most likely of all, it's Titanic. Most everyone has a shipwreck-associated cultural touchstone, synonymous as they are with fantasy-world romance, adventure, and fun, multipurpose phrases like "man overboard." They're like sarcophagi, or dinosaur bones: spooky old things, all with an allure that lies largely in their being objects out of place and time.Plus, pirates.Most people I tell about the search trip on Lake Superior ask me, in one careful way or another, partly embarrassed to be wondering but also partly suspecting I'll say yes, if what we'll be looking for is buried treasure. Even if only momentarily, you forget we're talking about ships that carried grains (or, at the most glamorous, iron ore) from one Canadian port to another. You think — just for a second — about people in eye patches carrying heavy chests of rubies and gold. But not once on my entire trip does anyone run to the boat's front railing to hold a bronze telescope up to his eye. That we — four pale Midwesterners sitting around and eating Doritos — could be doing anything but fishing would be unknowable to anyone boating past. "People usually ask why we're doing this," says Merryman, who wears a Great Lakes Shipwreck Preservation Society baseball cap and looks not unlike Michael Caine. He mimics them, adopting their perplexed tone, "'You're not getting money out of this?'" To him — to all of them — the motivation for shipwreck hunting is self-evident. Eliason and Smith have been shipwreck hunting together since 1980. They joined up with Merryman in the early '90s. Collectively, they have searched for and discovered dozens of other sunken ships across the Great Lakes. When I ask them what exactly they do when they find them — just because it seems like something should be done, something recovered or earned — they all laugh, unsure what to say or how to put it. In so many words, the answer seems to be: start looking for the next one. Eliason paraphrases Moby-Dick: "As Ahab said, 'Money 'tisn't the measure of man.'" He pauses. He wears glasses and a worn red sweatshirt with a ship stitched on the front in blue and gray, its name, U-656, stitched above it. It's a sweatshirt he wears so frequently out on these trips that he says Merryman makes fun of him for it. "'Getting the white whale — that's the measure of man."

The search for the Scotiadoc leaves from Grand Portage, a collection of buildings and people too small and scattered to earn the demographic title "town," but home to a fully booked lodge and casino. The territory is located in Minnesota's northeastern-most corner, six miles short of the Canadian border. A day before we leave shore I drive to the border station at Pigeon River to purchase a Remote Area Border Crossing Pass, a $30 permission slip that lets boaters glide from the Minnesotan part of the lake over into the Canadian part without needing to go through customs at Thunder Bay. Generally speaking, it's an easy enough transaction: You need a passport, and you have to fill out a few forms and then wait. You can make it harder on yourself than it needs to be if you accidentally drive down the wrong lane, leaving a mean immigrations officer with the impression that you were trying to skip the line because you are a special American. You can try to make up for the mistake by saying "Yes, sir" a lot. All told, it takes about an hour. I meet the group for the first time at the marina the next morning, a Saturday, at 5:30. Meeting someone this way — just after they've woken up from sleeping on a boat, just before leaving land for two and a half days spent in a space that is confined in every sense, all of us from that first moment in the very same clothes we'll wear start to finish, because changing them soon appears silly, impractical — is supremely and uncomfortably intimate. But we handle it like Midwesterners, which is to say that we just pretend it isn't weird and don't talk about it. Merryman puts my bag with the others and shows me my bunk, which is right above another where Smith is still half asleep. It's 40-some miles to the spot where we'll start searching, and it'll take us almost five hours to get there. As we prepare to leave the dock, Eliason picks a CD from a zippered binder and places it in the disc tray. It's the Beach Boys' "California Girls," a song I'll forevermore associate with what 30 seconds' worth of antsy adventurousness feels like before being struck with an acute seasickness the moment the boat accelerates past 2mph. Merryman's is not a boat that is especially kind to those with delicate senses of balance. The Heyboy is a 33-foot Owens Cruiser, built in 1946, with a wooden bottom that moves with the water more than it does through it. I was given fair warning, but I'm a Minnesotan who has been on her share of boats with no problem and didn't expect to have one here. In my defense — and I really feel I must present one — it's a windy day, and the waves on the lake fluctuate between 3 and 4 feet high. But those single digits look pathetic even now. Though I would like to, I cannot rightfully claim this is a noteworthy wave height. I'm told that other trips, up in Newfoundland, have seen them dealing with 10- or 12-footers. When they see I'm sick, Merryman and Smith encourage me to come up the two stairs to the helm, because sometimes seeing the water helps. Sometimes, though, it does not. "I took my grandson on a trip once and he threw up 13 times," Eliason laughs.

I spend the entire first day nauseous in my bunk, killing mosquitoes, trying (without much success) to eat a pretzel or two, but it's a small enough space to know I don't miss much. There are a number of reasons shipwreck hunting is a time-consuming hobby, and this is one of them: The self-designed camera equipment the group uses to scope out the bottom of the lake — this being the final step after painstaking research and sonar tracking — requires a specific, serene set of weather conditions. If it's sent down in too-active waters, it likely won't come back up. Even on the most promisingly forecasted weekends, the group typically expects to spend at least a day out of every three sitting around and waiting for more ideal waters. There's a TV on board for this purpose — at the first sign of choppy water, Eliason is quick to ask the others if they want to watch movies, which they choose on rotation. "Did we watch that one already this year?" Smith will ask of several offered options, but neither really remembers. In the end they settle instead on a boxed set of a TV show called Sea Hunt.

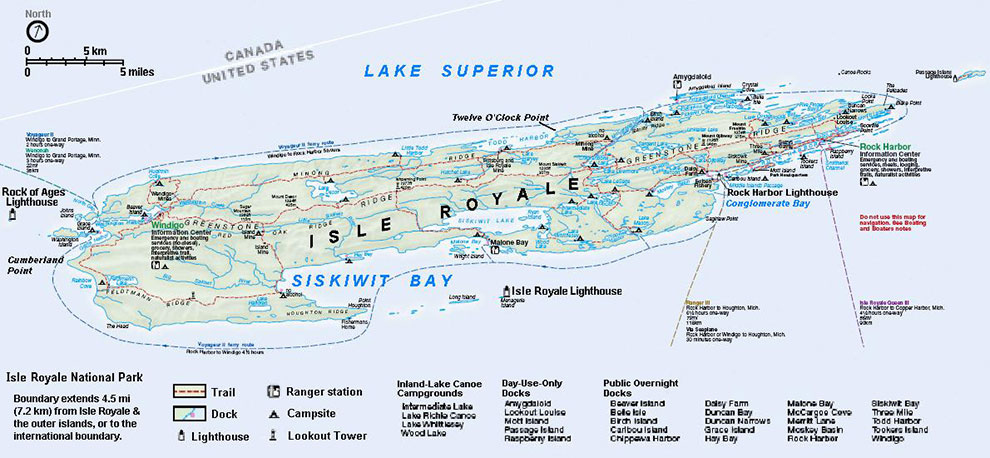

Sea Hunt was an adventure series that aired between 1958 and 1961 and starred Lloyd Bridges as ex-Navy frogman, "freelance scuba diver," and aquatic detective Mike Nelson. The series only ever aired in syndication, largely because major networks felt that a show with Sea Hunt's limited scope was unlikely to succeed. But the series ran for four seasons — 155 episodes total — and was extremely popular for many years afterward. "It was the biggest syndicated show on TV until Baywatch superseded it," Eliason explains. (Smith, who is by far the quietest of the group and spends a good chunk of our downtime reading a book about Jesus, says, "Hard to beat that.") "After it went off the air, my local station picked it up and played it at 8 a.m., and I'd get up early to watch." Lloyd Bridges as Mike Nelson, the crime-solving scuba diver, cuts an impressive figure in both a wetsuit and a regular one. He's blond and tan and fit — you lose some of the finer details in black and white, but this much is still clear — but not so muscular or handsome as to seem totally inimitable. His physical feats strain credulity just enough. There are aspects of the show the group now recognizes as laughable, but they're small, insidery jokes — the size of the scuba tanks, for one, or the show's unrealistic depiction of underwater visibility — details that wouldn't occur to a child enthralled. You can kind of see what the networks were getting at with the show's contextual limitations — there are an awful lot of inexplicable, motiveless underwater murder attempts; two of the four episodes we watch feature husbands trying to kill their wives for no discernible reason other than that they're "rich" — but if you find yourself drawn to Mike Nelson, you probably wouldn't care. And how could you not be drawn to Mike Nelson? Every other man on the show is jealous of him. Every married woman whose life he saves is in love with him. They don't say it out loud, but you can see it in their eyes, particularly when he's carrying them from sea to shore. Eliason and Smith in particular don't hesitate to give Mike Nelson credit for turning them into divers and shipwreck hunters. "[The show] was the inspiration for me and many in my generation," Eliason says. Throughout the trip the whole group mourns the fact that there don't seem to be many young people taking up diving and shipwreck hunting as sport. "Thirty years ago, this area would have been full of people in their twenties, diving Isle Royale," Merryman says. Instead, hardly anybody is out here but us. Eliason suspects the economy plays a role. When they were all young and earning minimum wage, he says, contrasting that time to now, they still had some money left over to spend on hunting trips. They make more now, and spend more doing it — Eliason estimates he spends 90% of what he calls his "fun money" on shipwreck hunting — but they also have an established group that splits expenses. The cost of new equipment, too, can be prohibitive — Eliason and his son Jarrod built their own side scanner in 2000, but before that, they made do with the fairly primitive tools they could afford. If I'm the youngest person out here by decades (and this is true for at least as far as I can see), Eliason is probably not wrong that money is part of the reason why. There's also the bad weather this weekend, though, and the fact that young people's hobbies just change, and maybe, also, it's partly that we grew up without our own Mike Nelson. It's clear he's with them even now. For the rest of the weekend, any time the weather proves too hazardous, or the discussion turns dreamily to an undiscovered shipwreck thought to be unreachable, they'll (somewhat disappointedly) admit their own limitations as humans bound by nonfiction. Moments later, without fail, something like this: "Of course, Mike could do it."

The areas of Lake Superior through which we'll pass in our attempt to find the sunken Scotiadoc are protected by a number of state and federal laws. To the north, the lake's designation as a National Marine Conservation Area — the first of its kind in Canada, passed in 2007 — prohibits drilling and other forms of "resource extraction," but does not exclude shipping or fishing. The area's boundaries at the United States–Canada borderline bump up against those of Isle Royale National Park, an 894-square-mile region including Isle Royale, smaller adjacent islands, and the waters around them. Below water level, within the Park's bounds, there are also 10 shipwrecks, all of which are registered as National Historic Places. A shipwreck's trip from found secret to registered property can be a contentious one. Until the 1987 passage (and 1988 signing by President Reagan) of the Abandoned Shipwrecks Act (ASA), shipwrecks and the property found within them could be claimed by individuals, under either the "law of salvage" or the "law of finds." The former — which dates back to the Byzantine Empire — granted a reward to anyone who voluntarily seized underwater property under the auspices of "relieving" it from "impending peril at sea." Generally this meant the "salvor" could count as his some 10–50% of the material goods extracted from a ship. The law of finds went further, occasionally allowing individuals to take possession of the title of a shipwreck (or property taken from it) if it could be considered expressly abandoned or if the original owner wasn't around to claim it. In other words: finders, keepers. The ASA was drafted with the recognition that so-called salvors frequently damaged what could often be considered archaeological and historical sites in hasty pursuit of financial gain. The law effectively handed shipwrecks over to the states they're found in, so long as the wreck is both "embedded" there and "abandoned." The vagueness of both terms has led to considerable confusion: Is a ship "abandoned" if its owner never gave it up but instead just… died? Does "embedded" mean it has to be partly buried, and that if you came across a chest of gold (fingers crossed!) sitting some distance away from a ship, neatly atop the sand, you could take it? (For the record, probably not.) There are modern-day salvors — like Odyssey Marine Exploration, people who work in the oceans with massive crews and expensive equipment, seeking out shipwrecks hoping to find some qualified version of pirate booty — but that sort of thing is technically called treasure hunting, and in that field the ships themselves are more or less incidental. And there are nominal shipwreck hunters who will illegally remove artifacts from the ships they find and keep them as trophies. But Merryman, Eliason, and Smith — along with other groups, many of whom are organized around the central principle of preservation — frown upon any human disturbance of the wrecks whatsoever. "When I started, I could see places [on the ships] where things had clearly been taken, and I got resentful," Eliason says. All they plan to do — all they need to do — is find them. The suspected location of the Scotiadoc, I'm told from the beginning, is much too deep for diving. Among skilled, experienced scuba divers like Merryman, Eliason, and Smith, 500 feet is considered the depth at which, Merryman says, "things change." Beyond that, heat retention can very quickly become a problem. The Henry B. Smith, the group's most recently discovered ship, is right near that threshold, and none of the three have gone down to see it up close. As they get older, they're increasingly selective about their diving. Eliason got the bends — or "wrecked [himself]," as he puts it — in 1989, and hasn't dived since. He has trouble walking and, off the boat, uses a cane. Merryman and Smith still dive, but much less frequently than they did when they were younger. "I'm slowly, begrudgingly settling into the fact that I'm not going to be able to do that anymore," says Merryman, the oldest among them at 64. At some point, flipping through his movies, Eliason will stop at the 1958 film The Vikings and say that its finale — in which a central character is given a Viking funeral, his body pushed out to sea atop a longship while his compatriots set it on fire with flaming arrows shot from their bows — will be the guide for Merryman's own funeral proceedings. It's a joke, mostly — though Merryman's affinity for the Heyboy is visibly, unquestionably that strong — but a slightly uneasy one, maybe because it seems cruel to acknowledge that he, or any of them, will ever have to stop looking for ships. It seems that the gradual giving in to viewing them only from above must be a loss great enough. To see them in pictures and videos taken from these depths is, of course, incredible. But to actually be there, eye level with a wreck, you and your partner alone in cool, dark silence, sure that it must be real because you could swim up and touch it, well — most of us can only imagine. With time — as tends to happen — the thing these three people love has changed, but their interest in doing whatever version of it they can is undeterred. They once went 13 years without finding a single ship. They call that period their "dry spell," but it's also fully one-third of the time they've spent looking for wrecks. It's all they want to do, so they keep doing it. "We used to look for wrecks shallow enough to dive," Eliason says. "Now we look for ones we can't dive." Look deep enough, and the young people — wherever they are — can't get down there either. And as the number of suitable shipwrecks left to find dwindles — each of the men can list off a few pet ships they'd still love to discover, but most of the Lake Superior wreck locations are now known — they find more time to revisit ships they've already documented. "Nowadays I can dive the same wreck over and over. I can't remember them from week to week anyway, so it's all new to me," Merryman laughs. "There's an advantage to being old. There aren't many, but that's one." He's kidding. He can remember every one. He isn't tired of talking about any of them. While he cooks lunch he tells me about one they dove years ago. "Now, Jerry," he says, "is the ultimate optimist." Apparently Eliason believed they could reach the ship with 240 feet of line, but Merryman insisted they add 50 feet more. With 290 feet of line, they barely made it.

Many of the thousands of shipwrecks located along the bottoms of the Great Lakes are precisely documented. The 2008 book Shipwrecks Along Lake Superior's North Shore by Stephen B. Daniel lists some 35 wrecks, including their depths, hand-drawn layouts, and occasionally their GPS coordinates. (Merryman and Eliason are both thanked in the acknowledgments — Merryman for diving and discovering many of the ships in the book, Eliason for his photographs.) But those are just the wrecks along the North Shore. In all of Lake Superior, Merryman says, there are approximately 400 of them. That there are so many wrecks in the Great Lakes is owed to two factors: first, the sheer number of ships that have crossed them since colonization, transporting immigrants and freight from various spots along the distance between the Lakes to the Atlantic Ocean, or between New York City to New Orleans, to others. Second, the vastness of the Great Lakes lends itself to sudden and often dangerous changes in weather, with waves that, on the larger lakes, are known to regularly reach 20 feet. A November storm in 1913 — so heralded it's been given three nicknames, including "Big Blow," "White Hurricane," and, my favorite, "Freshwater Fury" — earned the label "extratropical cyclone," blowing 90 mph winds through the lakes, producing whiteout blizzard conditions and waves over 35 feet high. That storm alone killed over 250 people and sunk 12 ships. Four (the Leafield, the James Carruthers, Plymouth, and the Hydrus) have never been found. The 1913 storm might have been the Great Lakes' worst, but it was far from their only. Though a few of the shipwrecks in Daniel's book are described as the products of Disney-esque chance encounters — an unknown wreck at Minnesota Point, for instance, was spotted by a young girl named Sophie who was ice-skating over it with her father — most begin with shipwreck hunters in a library. For example, the Onoko: "Divers Jerry Eliason of Scanlon, Minnesota and Kraig Smith of Rice Lake, Wisconsin, conducted extensive research on the Onoko and then spent considerable time searching the lake southeast of Knife River, Minnesota, with a depth finder. They found the wreck on April 10, 1988."

In June the group made news for locating the 1906 freighter Henry B. Smith about 30 miles of the coast of Marquette, Michigan. The ship is the most recent find from the aforementioned 1913 storm. They found it, in part, by using data processed by Eliason's wife — who, though not a shipwreck enthusiast herself, is a skilled software engineer willing to lend her expertise from time to time. What kind of data? What kind of processing? I ask him all weekend, but Eliason is cagey. All he'll say is that they were working with "millions and millions" of numbers that are "geologic in nature," and that they were obtained using the Freedom of Information Act. The Scotiadoc is different; here, Merryman, Eliason, and Smith started simply with a book. Julius F. Wolff's Lake Superior Shipwrecks (1990) describes the ship's collision and eventual sinking. Picture a square hovering above the water off Trowbridge Island, maybe 100–200 miles wide and long: This, roughly, is what they started with. From there they checked newspaper archives and the 500-page formal investigation into the collision. In some cases, legal documents exchanged between shipowner and cargo owner after a wreck provide clues that never reach the public. Records like these helped the hunters narrow the scope. Eliason keeps the range drawn on a white poster board, each 1-inch square representing a square mile. An X is already drawn over every one — because, again, they've been looking for years — but there are a few areas marked as deserving of a second look. They tell me that if they find the ship this weekend, it'll be somewhere they already checked. The prospect seems to delight them more than it does frustrate them, though there might be a little of that too. If any of the three men went into this trip with a good feeling about what the camera might find beneath us, I'd have had no way of knowing. They are so carefully measured, so thoroughly Minnesotan. The best way I could possibly describe what that means was given to me in a story told, in alternating sections, by Merryman and Eliason, one stepping in to continue whenever the other began laughing too much to speak. The first time they went out shipwreck hunting together on the Heyboy — having known each other only briefly, having decided to join forces after Merryman "wore out" the rest of his friends' interest in diving trips — each noticed a rotting smell that got worse with every hour that went by. Each believed the other was personally responsible, and each privately decided that there wouldn't be future hunts between them after this one was finally over. And even though it was that bad, neither said anything to the other about the smell. "We didn't want to offend each other," Eliason explains. So they kept sitting and eating and sleeping and diving, all the while pretending their tiny, shared living space didn't smell increasingly like death. Three days later Merryman found a mouse that had crawled into the side scanner's reel, become stuck, and died. Conflict avoided. None of this is to say that the shipwreck-hunting world is without its own insular and strangely satisfying dramas. The word among Lake Superior shipwreck hunters is that the hunting groups who work in the lower lakes — Lake Michigan and Lake Huron in particular — are fiercely competitive. "We hear stories," Eliason says cautiously. "The [groups] down there don't like each other." If there isn't treasure to claim, there's always territory: One group finds a wreck first, or claims to, and another says no, actually, they did. It's an insurmountable argument technique, painfully familiar to anyone with a sibling: "Newly discovered, the SS _______!" "Oh, that boring thing? We found it ages ago." "Really? So where is it?" "Right where you just said." Up here, relations among various shipwreck hunting groups are, generally, more amicable. Eliason does tell me about two hunters he knows who can't stand each other. It's the same type of story — both claim credit for finding a ship first, and if you know them, you have to pick a side. But theirs is the only Lake Superior-based shipwreck hunter rivalry that comes to mind, which is not altogether surprising.

The third and final day of the search for the SS Scotiadoc finds Lake Superior covered in a fog so dense it looks like we're sailing into nothing but white. The water is, unexpectedly, almost eerily calm. It's a Monday, which they've all taken off work; Eliason works as an assistant regional supervisor at the Minnesota Department of Public Safety, Smith as a CFO to a manufacturer of weighing equipment. Merryman works as a computer design engineer, but also runs a charter service on the Heyboy called Superior Trips. To get everyone home in time to go back to their respective offices on Tuesday, we'll only be able to stay on-site until early afternoon. The plan is to return to a spot we visited yesterday, for which Eliason marked the coordinates on his whiteboard map with a highlighter. There have often been searches that have required these shipwreck hunters to examine 50–60 square miles or more, and the Scotiadoc is one of them. When covering an area that size, they start by sending down a side scanner — a class of sonar system that casts wide beams over the lake floor and picks up sound signals from hard targets like shipwrecks. The closer they are, the stronger the signal. Side scanners are efficient, though perhaps only in relative terms: In order to be thorough, the largest area that can be covered with one in a daylong search is about six square miles.

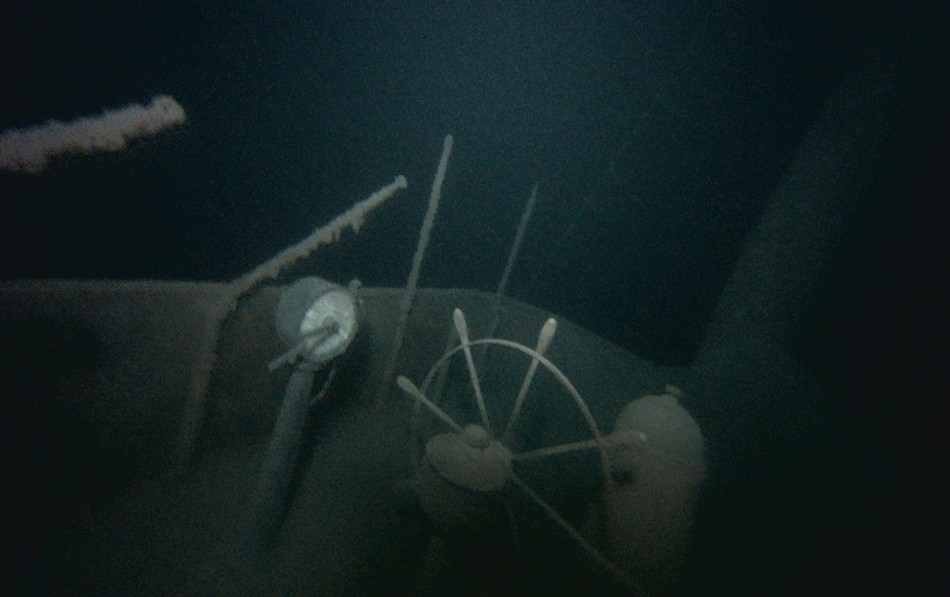

A day earlier, before the lake grew too stormy and the Heyboy retreated into Tee Harbor, the side scanner picked up on a slight "bright spot," or a spike on the sonar. There appeared to be an unusual, disturbed-looking piece of "geology," the diver's catchall term for naturally occurring terrain change. It wasn't a decisive clue, but it was the best one they had. It takes some time to uncoil Eliason's custom-designed camera, which is waterproofed in a plexiglass box. They send it down gently, hoping to avoid losing it to the lake, though they seem to accept this as a permanent possibility. It's just before noon by the time the camera is at the right depth. It's switched on, and we watch what it sees on the TV inside the cabin. Though the surface is right there, and water is all I can see in every direction, everything beneath it — made plainly visible on the screen in front of me — seems impossibly distant. It looks just the way you'd expect the dark bottom of a lake to look, but from above, inside a boat, it feels illicit, like something we shouldn't be allowed to see. We approach the target area, circling it, overshooting it and then coming back. It's not like holding a metal detector over the sand; your surface moves. Soon we see a textural change along the lake bottom, like rows of some darker material neatly arranged. "Could that be wheat?" Eliason asks, and somehow as he's asking the question, I could feel it coming up just off the edge of the screen. Moments later, orangey and ancient-looking, unmistakably man-made and identifiable even in ruins, it's there, 850 feet deep: a shipwreck. Merryman is laughing and yelling. "Whoa — what — fuck! FUCK, we're good!" Eliason, too, hollers, his voice jumping up a few octaves in excitement. Merryman asks him if he started the tape they'd set up to capture the ship if we found it, and Eliason nearly squeals, "I was too excited to press record! I can't — I can't find the record button on here!" In other circumstances it might have occurred to me to take the remote and look, but even I can't take my eyes off the screen. We actually found it. I mean, they actually found it. But still. It takes no more than 30 seconds, and probably much less, for what little wind there is to move us past the wreck entirely. In that same amount of time, the men collect themselves and, already, start talking about which ships they'll find next. They've got two in mind: the Steinbrenner and the Leafield. "When things need to happen, they do," says Merryman. He explains that maybe it makes some symbolic sense to find these sunken ships — for, it's implied, the ships to want to be found — after some nice, even number of years. They found the Henry B. Smith 100 years after it sank. The Scotiadoc, which we glided over seconds ago in the year 2013, sank in 1953. The Steinbrenner sank in 1953 too. The Leafield, 1913. So, we'll see. As we turn the boat around to go back over the Scotiadoc, hopefully with the record button ready to go this time, Merryman adds: "But we're not superstitious or anything." We pass over the ship twice more, viewing it from enough angles to know the Scotiadoc has seen better days. It definitely was a ship, but now it is a scattered assortment of beams and ladders and pieces of wall. It's no Henry B., as they call it affectionately. "I'm sure we'll never see another wreck more beautiful than that one," says Eliason. A day earlier, while Merryman tended to boat maintenance, he and Smith had watched, in silence, a little of the underwater footage from those days in June, when they'd found it. The camera rolled over whole rooms of the ship, black-green and rusty. It wasn't like the ships you'd see on Sea Hunt or anything, but it was standing upright, and it was real, and for a little while they were the only people on the planet who knew it was there.

In Canada, sensibly, it's illegal to drink and drive a boat. This law is studiously — if mildly resentfully — abided by everyone aboard the Heyboy. A few hours after discovering the Scotiadoc, back in the more lenient waters of Minnesota, Merryman, Eliason, and Smith celebrate with a beer. Finally, just in time for the very end of the weekend, I've got sea legs. I use them to sit up where I can see the water, on a cushioned seat behind the helm, while we drive back to shore. It's still so foggy that, even though I know they've got the coordinates, it's hard to believe they'll ever be able to return to the exact spot where we were when the camera picked up that first beam. But of course they will. They'd like more photographs, and, if they can get it, video of the name Scotiadoc written across the bow. They know it's the Scotiadoc, that it without question has to be, but this is the sort of definitive documentation needed to close the case for everyone else, to tie the pieces back to the whole that sank in 1953. Eliason, cradling a bottle of Budweiser, tells me, "Finding these shipwrecks is kind of like writing the last chapter in their history." Merryman, at the wheel, laughs. "That was profound, Jerry." He grins. "The more beer I drink, the more profound I get." A few weeks after returning safely to land (and a few weeks minus one day after I stop feeling, when standing still, like I'm on a wavering boat), I send Eliason an email to check in and ask whether they've yet returned to the Scotiadoc. I catch him on the night before he and the others are leaving to head back up north to do so. There are a number of lost ships they plan to find — among them those celebrating anniversaries, the Steinbrenner and the Leafield — but in response to my asking what they'd focus on next, Eliason picks out one in particular: the U-656, the first German U-boat sunk by U.S. forces in WWII, off Cape Race in Newfoundland. This, I later realize, is the same ship featured on his red sweatshirt. Eliason tells me that the week prior, he learned that a member of the U.S. Navy who was on the Lockheed Hudson bomber responsible for sinking the U-656, Truett Hawley, is alive in Texas; he's 94 years old and "sharp as a tack." (Attached to his email back to me, Jerry sends an illustrated picture of a Lockheed Hudson. "I used Photoshop to change the number to match the one they were in," he writes.) He and his son, Jarrod, plan to visit Hawley to hear firsthand about the attack. Eliason doubts Hawley will be of any help narrowing down the U-656's exact location, and why should he be? He did exactly what his job required him to do, which was to sink it. Finding it all over again is up to someone else.

(Correction: A previously published version of this story incorrectly identified Lake Huron, 9/6/13)