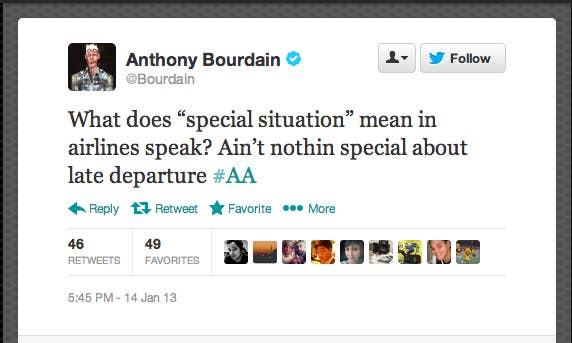

Earlier this year, celebrity chef and TV personality Anthony Bourdain suffered a flight delay.

The details of the delay ended up being on the...unusual side (it was reported that a bathroom-related accident took place outside the airplane bathroom, leading American Airlines to switch the plane planned for use in Bourdain's flight), but the general inconveniences associated with his travel plans were not: A person had to wait longer than expected to get where he was trying to go. It was a hassle.

The difference between Anthony Bourdain and any other dissatisfied customer of American Airlines is that Anthony Bourdain has over 1.3 million Twitter followers. When he took to Twitter to publicly complain about the airline — giving his rant its own hashtag home — 1.3 million people were there to listen.

Noted calm and reasonable person Alec Baldwin, too, was famously bounced from an American Airlines flight, allegedly for becoming disruptive after a flight attendant asked him to turn off his phone in preparation for departure. He subsequently tweeted his version of the events to his then-600,000 followers, criticizing the crew (whom he called "retired Catholic school gym teachers") and ultimately vowing never to fly with American Airlines ever again.

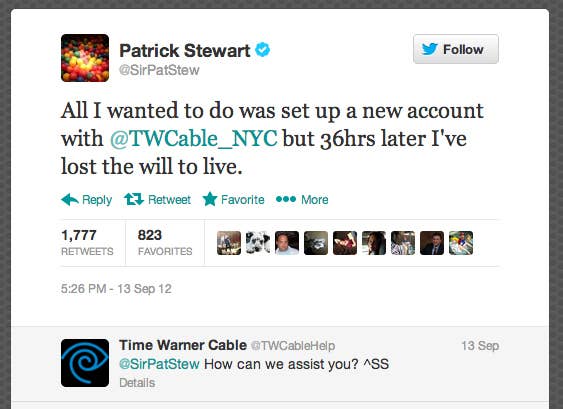

And when actor Patrick Stewart had trouble setting up a new account with Time Warner Cable last fall, his audience of over 330,000 followers was there to commiserate — and in some cases, to share their own grievances in the form of tweets back at the actor and the company itself.

That celebrities, in particular, would grandstand about their customer service expectations and woes is not, in itself, surprising. Nor is it the case that giant corporations deserve special protections, especially in times of poor performance. What is notable (and, in terms of online etiquette, troubling) is the spillover effect these celebrity tirades are having on the common Twitter user and, in turn, our Twitter-adjusted expectations for customer service.

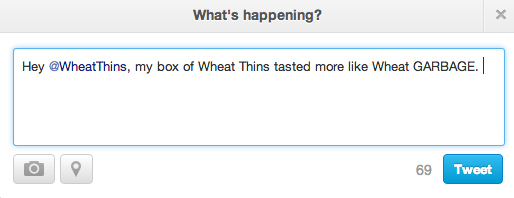

Increasingly, Twitter users aren't just looking for actual customer service on the site — they're using their accounts to broadcast their complaints.

The practice has even gained traction with social media "gurus," who write articles providing tips on how the average Twitter user can more effectively address customer service. Many of these tips are merely instructive, suggesting that users who want assistance tweet directly at the company, as opposed, I guess, to subtweeting them. But others are more combative, and maybe just a little alarmist: "You also have the option to tag other account in the tweet, in order to raise the profile of the complaint," writes social media consultant Lauren Dugan. "Think about who might be interested in this story — prominent journalists, consumer advocacy groups, local politicians."

Surely in almost every case the answer is, emphatically, "none of the above," but what's more concerning is the sentiment behind the suggestion: the assumption that each and every customer service complaint is Twitter-worthy and deserving of public attention. They're not.

Regardless of whether it "works," using Twitter to publicly complain about your minor issues and inconveniences with a company is extremely obnoxious. (Note that this does not apply to one-on-one @-replies between you and the company. That's your business!) For one, the practice smacks of entitlement. Travel delays and cable difficulties are a pain, but, well, what else is new? Taking one's complaints to Twitter (and especially asking your followers to join in) suggests a belief that one's personal inconvenience weighs more than others and is thus deserving of an audience. It hopes that, because you have the number of Twitter followers you do, the company will notice you as important and resolve your complaint — faster than it would for the average call-in citizen.

The public Twitter complaint is, in that way, rather undemocratic — where a site like Yelp gives equal weight to its anonymous reviews (but also necessarily quiets the more extreme reviews in favor of the average opinion, by the sheer number of reviews present), Twitter makes it easy for one dissatisfied customer with a megaphone to make his or her opinion count (or at least believe that it counts — which is bad enough as it is) more than the rest.

And while it's probably not worth losing sleep over American Airlines, the corporation, it might be worth thinking about the individuals on its Twitter customer service account and others like it. Is a resolution really even the goal, or is it applause? For those who feel quite comfortable making a show of live-tweeting their complaints with various companies but who don't exactly feel like calling that 1-800 number, it might be best to do that thinking — like Lauren Dugan said, sort of — and keep the hissy fits offline.