If you're in the mood for a dark, disturbing, often-uncomfortable journey through a long-gone version of New York City: Cruising (1980, William Friedkin)

William Friedkin’s potent, pungent thriller Cruising opens with an echo of Taxi Driver — a beat cop (played by late character actor extraordinaire Joe Spinell) driving in his cruiser stares at male prostitutes on the streets outside and bemoans the state of things: “One day, this city’s gonna explode… Christ, what’s happening?” Shortly thereafter, the cop and his partner pick up two transvestite hookers for the purposes of indulging in the other, more prominent meaning behind the film’s title. Uncontrollable urges, whether the kind evinced by Spinell’s closet case or the more deadly kind indulged by the film’s sadomasochistic killer (who’s apt to close his killings with a hissed, “You made me do that”), are the driving force behind Cruising, as thorny and off-putting – yet compelling – a film as ever put out by the Hollywood machine.

The film certainly courts charges of homophobia – as undercover cop Steve Burns (Al Pacino) delves deep into the leather-and-hankies S&M underworld of the gay underground in pursuit of a deranged man preying on pickups, one could certainly sense a level of demonization here. (Gay sex is freaky and will get you killed!) Except Friedkin’s a lot smarter than that – from the outset, he ties the club scenes together with driving punk rock, another form of brash outsiderdom that represented a break from the civilized world. Friedkin’s direction is visceral and unblinking – he only shies away from the graphic sex insofar as he needs to preserve an R rating, and the violent sequences are cut to the bone, showing death in a flurry of images and blood – and he gets an appropriately dazed performance from Pacino. Ultimately, Pacino’s climactic confrontation with the killer pales next to the confrontation of that previously unacknowledged uncontrollable urge — the terrific, ambiguous final shot shows a conflicted Pacino staring in the mirror, still feeling that urge, not knowing what to do with it now.

If you're in the mood for a clinically insane action movie where people erupt like meat balloons: Riki-Oh: The Story of Ricky (1991, Ngai Choi Lam)

There’s good versus evil, and then there’s Good Vs. Evil. The former has room for nuance and subtlety; the latter exists only to be blown up to comic-book proportions and decorated with extravagant grotesqueries. In this vein, few films come more comic-booky or grotesque than the amazing, ridiculous Hong Kong prison/kung-fu/splatter movie Riki-Oh: The Story of Ricky. Ricky, the hero, is pushed so far into god-mode invincibility that he stops being a person and instead feels like a brawny ideal – Pure Good made flesh.

People in this film aren’t beaten up when they can be dismembered, shattered or liquefied. Paper-mache heads are crushed, bodies are exploded and holes are punched straight through people in wet, meaty demonstrations of impossible strength. (Remember that exploding head sequence that capped the Daily Show when Craig Kilborn was still hosting? Riki-Oh.)

People turn into muscle-bound monsters, burst through walls like the Kool-Aid Man and cut their own intestines out just to have something with which to strangle an opponent. Ricky’s righteous fury renders him incapable of incapacitation – shoot him and he’ll act like nothing happened, punch him and he’ll grit his teeth and shrug it off, sever the tendon in his arm and he’ll just fucking tie it back together. The finale, set in a prison kitchen and featuring prominent use of an industrial-strength meat grinder, contains more spewing chunky tomato-paste carnage than any film not named Dead Alive. Giddily sick and energetic to a fault, Ricky is essentially kung-fu cinema if your idea of kung-fu cinema is a deranged Warner Brothers cartoon, and for a certain type of viewer, its entertainment value is astronomical.

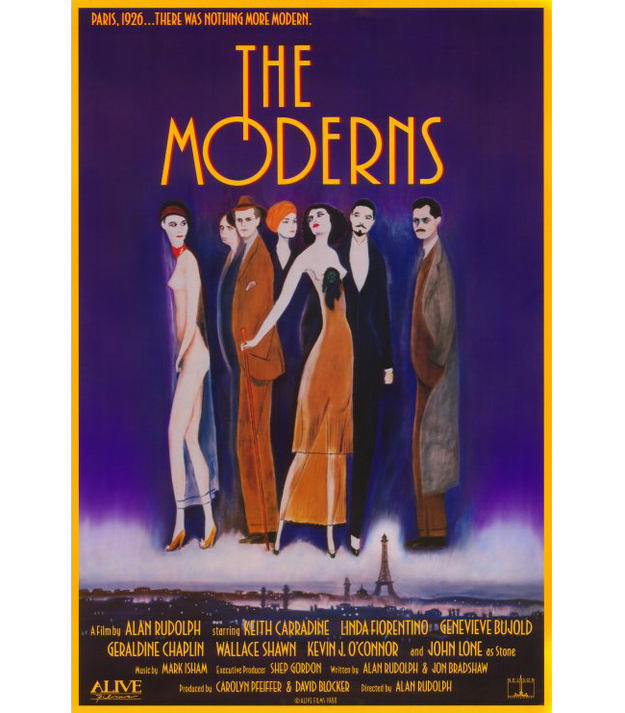

If you're in the mood for a light-on-its-feet tale from the Lost Generation: The Moderns (1988, Alan Rudolph)

Late in Alan Rudolph’s Lost-Generation charmer The Moderns, Wallace Shawn muses, “Paris has been taken over by people who are imitators of people who were just imitators themselves.” The fact that he’s saying this to Nick Hart (Keith Carradine), a man who’s spent a large amount of time forging copies of three well-known paintings, is but one of a number of ironies that run through the fabric of the film. Hart is here to make art and sell it, though a patient dealer (Genevieve Bujold). Nathalie de Ville (Geraldine Chaplin), on the other hand, wants to keep art for herself – thus the commissioning of the forgeries, as a ruse to deceive the husband whom she’s leaving. And Bertram Stone (John Lone) is looking to acquire any art he can that will gain him the respect he feels he deserves.

Art, commerce and authorship all come up as subjects of examination and sport, fought over by fringe talents and art-world hangers-on while genuine famous artists (Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway among them) drift through as a reminder of why all the imitators would want to be there in the first place. Setpieces are often busy, with overlapping dialogue and easily-missed little jokes, like Hemingway (played with hilarious unease by Kevin J. O’Connor) at a boxing match shouting, “I AM THE ONLY ONE THAT RINGS THIS BELL!” (In scenes like this, it’s easy to remember that Rudolph was a protégé of Robert Altman). This could all come off real clumsy if handled poorly, with present-day knowledge and easy snark choking out any attempts at legitimacy; fortunately, Rudolph has a steady hand on the material. His dialogue, infused with a strong yet laid-back sense of humor, sways agreeably between droll and silly, and neither does the film falter or get heavy-handed when it shifts into more dramatic territory. It’s an elegant, self-assured work, akin to a lovely and funny reminiscence one might hear over coffee and brandy that resonates more than expected; when Shawn wraps up his broadside against Paris with, “Believe me, Hollywood is gonna be like a breath of fresh air,” we know the punchline is truly yet to come.

The Netflix streaming library is vast and daunting and mostly filled with crap. Steve Carlson is the Netflix video clerk, and every week he hand-delivers three awesome movies you've never heard of before. He's been writing about movies in one form or another on the Internet since 2002 and co-hosts the Bad Idea Podcast. Someone once called him the lonely Magellan of exploitation cinema. He thinks that's the best compliment he's ever received.