Update — 8:47 p.m. ET:

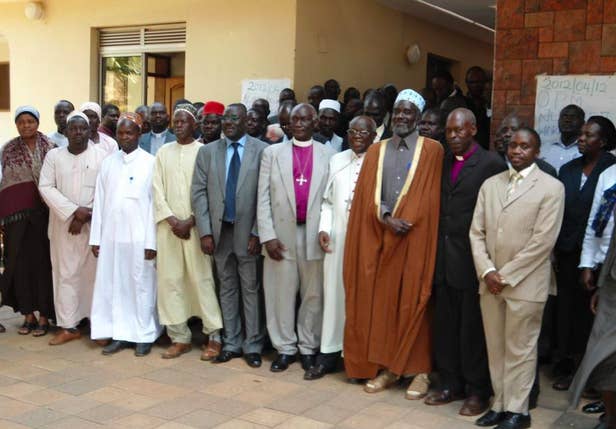

Early last month, as Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni weighed signing a brutal new anti-LGBT bill into law, the Inter-Religious Council of Uganda (ICRU) published a statement urging religious leaders in the country to "highlight the dangers of homosexuality and lesbianism."

It told them to "champion the campaign against foreign influences that undermine moral heritage in the guise of human rights and freedoms," in the statement, published in the Uganda Daily Monitor and read by thousands. Support from the organization and its affiliated church leaders — including the Catholic Church, Anglican Church, and other major denominations — gave it moral legitimacy.

At the same time, the group has received millions in U.S. government grants for years to fight HIV. Why was the money going to a key supporter of the Anti-Homosexuality Bill, which the the U.S. government has officially opposed?

"I cannot understand the thinking within the State Department and PEPFAR" in continuing to provide grants to the group, said Kikonyogo Kivumbi, executive director of the Uganda Health and Science Press Association, referring to the president's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). ICRU's affiliates are important health care providers, and the organization received more than $3 million from PEPFAR in 2013.

"There is a frustration on this side, that [U.S.] quiet diplomacy and engagement with IRCU is not doing enough to bring results," Kivumbi said.

U.S. government officials were aware of IRCU's anti-LGBT advocacy dating back to at least 2012, according to emails provided by Kikonyongo and shared with USAID's then-health director in Uganda Karen Klimowski and other officials at the State Department and CDC. The Council for Global Equality, which advocates for LGBT rights in U.S. foreign policy, has also been objecting to this funding since at least 2011, according to the organization's senior adviser Julie Dorf.

"The amount of money that our government has invested to support LGBT civil society pales in comparison with the millions we've spent funding homophobic [HIV program] implementors in Uganda, who actively advocated for further criminalization of LGBT civil society," Dorf said. IRCU's funding needs to be shut off, she continued — U.S. policy has to be able to account for when religious organizations go "from hating the sin to hating the sinner and actively working on fomenting anti-gay sentiment in a country."

Late last year, the inspector general at the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) looked into concerns that PEPFAR funds were being used to promote Uganda's Anti-Homosexuality Bill and turned up nothing in its review that indicated PEPFAR dollars were supporting the organization's advocacy for the Anti-Homosexuality Bill, however it noted that it had not conducted a comprehensive audit.

If the HIV money was not being diverted to this lobbying work, it had done nothing in violation of U.S. policy, it said. It further implied that the State Department could not cut off funding to a religious organization on the basis of its religiously motivated political advocacy. In keeping with the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, the report said, "a religious organization may continue to express its religious beliefs after it receives financial assistance."

But that wasn't the only argument for continuing its funding, said a senior Obama administration official speaking on background in line with administration policy. If the U.S. government simply pulled IRCU's funding, the official said, many HIV patients would suddenly be unable to get their medication.

"What we're talking about are tens of thousands of people receiving HIV treatment and care," the official said. "We have a responsibility to ensure that those people continue to receive the lifesaving treatment they need. Cutting off aid would harm the people we're seeking to help, which is why we're looking at these issues thoughtfully and deliberately."

The U.S. is currently "taking a close look at how we can best support and protect the very LGBT populations the law seeks to discriminate against," the official continued.

The fact that IRCU continued to receive these funds is an indication of just how difficult it will be for the U.S. and other donor nations to "divert" funds to ensure LGBT people receive services in countries hostile to LGBT people. The problem is not new — more than half of the 88 countries supported by PEPFAR criminalize homosexuality, and in countries like Uganda and Nigeria, persecution is increasing.

In these countries, there are no simple ways to redirect large amounts of money to providers who can effectively use them while providing safe and fair treatment to all patients. Only a very small portion of the more than $409 million in health care aid that the U.S. earmarked for Uganda in FY 2013 go to the government itself. And there really aren't that many organizations that have the capacity to absorb millions of dollars and effectively deliver services in a nondiscriminatory fashion, especially in a place where there is as much hostility against LGBT people in a place like Uganda.

This is part of the reason that human rights advocates disagree about how to respond to the IRCU. A coalition of Ugandan advocacy groups that has come together to oppose the law does not agree with the U.S. advocates who are calling for the IRCU's funding to be shut off.

"We DO NOT support cuts in support to NGO's and other civil society institutions that offer life saving health services or other important social services to the People of Uganda," the group said in a press release after the bill's enactment.

Given the IRCU's reach, there's not much choice but to try to insulate the organization's health care functions from its religious leadership, Kivumbi said. Some parts of the country have no other providers beyond those affiliated with IRCU, he said. Even government clinics are scarce. Kivumbi said he would like to see the IRCU pressured to create an independent health secretariat within the group, but even that wouldn't fully insulate health care workers from the attitudes of their religious leaders.

"What you say from the pulpit affects service delivery," he said. "It is not easy to understand how they will do it."