The future: let's bet on it! There are so many ways to pretend you have a crystal ball and then put money on your misty prognostications. Wall Street. Prediction markets. Office pools. Vegas.

In this week's New Yorker, James Surowiecki argues in favor of legalized sports betting, which is now permitted in only four states (Nevada, Delaware, Oregon, and Montana). New Jersey voters approved an amendment in 2011 to make sports betting legal, and the DOJ, the NCAA and the four pro sports leagues have taken to the courts to stop them. He writes:

Of course, politicians are also responding to the influence of the major professional sports leagues. The leagues insist that legalized betting will make people suspect that games are fixed, thus harming their brands. Yet in Vegas billions are wagered legally on sports every year, apparently without ill effect, and legal sports betting in Great Britain doesn't seem to dim anyone's passion for Premier League soccer. Moreover, as Drazin said to me, betting is already an integral part of sports in the U.S.: "If gambling is really hurting the leagues, why does every sports show talk about point spreads and favorites and underdogs? And why does every office in America have a pool on the N.C.A.A. tournament?"

In Surowiecki's 2004 bestseller, The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many Are Smarter Than the Few and How Collective Wisdom Shapes Business, Economies, Societies and Nations, he offers a primer on behavioral economics and game theory that draws on gambling, Wall Street and other large crowdsourced systems to develop the idea that crowdsourcing information results in high predictive successes.

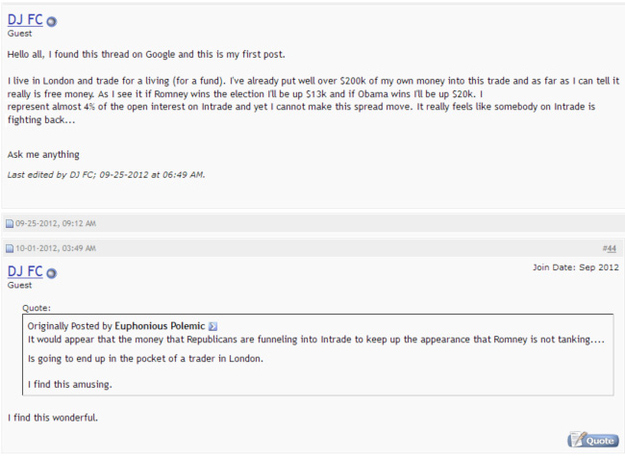

The potential pitfalls of giving this idea too much credence were evident during the last presidential election, in the provocative tale of the London traders who made a small killing off the unwarranted hopes (or, possibly, the bought-and-paid-for shenanigans) of Republicans in our recent Presidential election, during the course of which free money was handed out for a number of weeks in the commercial prediction markets. Yes! Real live cash dollars. That is because a rock-solid riskless profit opportunity ("arbitrage" in Wall Street lingo) mysteriously emerged in the form of a discrepancy in the odds on the U.S. presidential election between the UK-only prediction markets (e.g. Betfair and Pinnacle), and Intrade, the Dublin-based market which until very recently also operated in the U.S.

As the elections approached, forums all over the Internet lit up with discussion as to how best to exploit this inexplicable opportunity, which worked like this:

Question for gambling experts

[...] So here is my strategy: Sell $1,000 against Obama on Betfair, and immediately hedge the potential payout by buying $1440 worth of Obama contracts at the price of $1440*0.635 = $914.40 So, right now, I pocket $1,000-$914.40 = $85.60 I also know Betfair takes 5% of the profits, while Intrade charges a very small fixed monthly fee, but no profit cuts (I think it's $20, but I'll consider it a sunk cost of being on Intrade, and probably trading like crazy). If Obama wins: I make loss with Betfair (so no payment to them), and I pay the Betfair counterparty with my $1440 I won on Intrade. I keep the 85.60 I made today.

If Romney wins: I make $1,000 profit with Betfair, they take 5% ($50), I am thus left with $85.60-$50 = $35.60. Either way, I make a pretax return between 8.56% (if Obama wins) and 3.56% (if Romney wins) - risk free, instantaneously. With the possibility of repeating, until [the] prices converge. Even if I have to keep my money deposited, that market will close very soon, with elections one week away.

In other words, because there was a spread between Intrade's odds on Obama (around 65 percent to win) and those offered by the far larger UK sites (Betfair consistently hovered around 75 percent), it was possible to arrange for a small but guaranteed return. Clearly, this guy should be running a hedge fund.

As it happens, however, Americans will no longer be allowed easy pickings such as these, because Intrade closed up shop here on December 23, 2012. This was in response to a lawsuit filed by U.S. regulatory authorities, a move some have attributed to political motivations.

On Nov. 26, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (yes, the same U.S. government agency that failed to regulate the market in exotic credit derivatives) filed a suit against Intrade to enjoin it from further activity in the U.S. Bloomberg Businessweek reported that some 10,000 American punters would henceforth be unable to make (or lose) real simoleons betting on election outcomes, Oscar winners and so on, though the action in the UK will remain unaffected (with Argo heavily tipped to win Best Picture at current odds).

What, you may ask, is the harm in betting on any old thing you like? In England they can pretty much bet on whether or not your toast will land buttered-side down. Are they the crazy ones, or are we?

The history of "novelty" or "proposition" betting in the U.S. has been a vexed one, despite the recent passage of laws intended to relax restrictions against it. Unlike ordinary bets on games of chance or sporting events, which have had fixed regulations in place for about forever, betting on the outcomes of dog shows or celebrity pregnancies is vulnerable to the participation of those in possession of inside information. How to ensure that the interests of fairness will prevail? In 1980, for example, the Castaways casino offered odds on the outcome of the popular TV show Dallas. But it quickly emerged that altogether too many people knew Who had Shot J.R., and were not unwilling to profit by their knowledge; the Nevada Gaming Control Board intervened, and all stakes had to be refunded. Difficulties like these have generally meant that spoilsport gaming control boards charged with regulating gambling have turned down attempt after attempt to book such bets.

According to vegasinc.com, the last legal novelty wager in the U.S. was placed in 1979, when the onetime El Cortez casino took bets on where bits of the Skylab satellite would crash to earth (the eventual winner, Australia, paid out at 30-1.)

If insider betting is an issue with the gaming regulators, betting on politics complicates matters still further — there's the potential for corruption, the weight of ideological imperatives and so on. (If you're interested in the details regarding betting on elections, Paul W. Rhode of the Univ. of Arizona and NBER and Koleman S. Strumpf of the Univ. of Kansas School of Business wrote a most fascinating paper, "Manipulating Political Stock Markets" analyzing a century's worth of data on this subject. It turns out that you could make legal bets on Presidental elections right on Wall Street between 1880 and 1944. Who knew?)

Perhaps because U.S. citizens were allowed to place bets at Intrade (in contrast to the other UK prediction markets), it was Intrade's numbers that had all the play from U.S. media during the campaign season. When we consider how avidly these numbers were being watched by the press, and how little cash would have been required to game them, it would seem like child's play for the likes of Karl Rove's Crossroad GPS to have done just that. But there was a wrinkle; Intrade's UK-only competitors, such as Pinnacle and Betfair, are huge — and therefore far less vulnerable to tampering. To give an idea, the publicly traded Betfair's current market cap is in the neighborhood of 700 million sterling, whereas the privately-owned Intrade is nowhere near a tenth as large, if the (quite credibly derived) estimates of punters on its own forums are to be believed. As an excellent analysis by Daily Kos diarist Skipbidder pointed out on November 4th: "More money has been wagered today on Pinnacle in the US Presidential election than in TOTAL on Iowa Election Market this year." It's possible that the existence of large and reliable UK prediction markets was a kind of insurance against gaming the Intrade numbers too far, in much the same way that exit polls limit the possibilities of electoral cheating by potentially raising the red flag.

Faced with the might of the CFTC (and no doubt mindful of the various UK gaming executives under indictment or even jailed for their online activities in the US), Intrade caved, offering on their homepage this meek rejoinder to talk of their legal troubles (since removed):

"The report of Intrade's death was premature"

We understand our recent announcement [of the decision to close up shop] was met with surprise and disappointment by our US customers, but this in no way signals the end of Intrade in the US. In the near future we'll announce plans for a new exchange model that will allow legal participation from all jurisdictions - including the US. We believe this new model will further enhance Intrade's position as the leading prediction market platform for real time probabilities about future events.

There has been talk that this "new exchange model" might mean a so-called "play money" site like the Hollywood Stock Exchange, but that is unlikely to fly, given that their customers will hardly accept play money having once been given the chance to play for real stakes. Or maybe Intrade can pinky-promise the CFTC that they really really will be very very good from now on, and stay entirely away from operating an unregulated market in commodities options, which seems kind of unlikely too, on the face of it. (The best full-dress rundown of the Intrade hoo-ha is in this Financial Times piece from Gregory Meyer and Arash Massoudi, but it's partly paywalled.)

But it was the fact that the CFTC came down on Intrade so close to the recent elections — fully seven years after a deal had been struck — that raised many an eyebrow. As Meyer and Massoudi observed: "Among concerns: the [election-related] contracts threatened to sway voters with monetary incentives." And there were subtler election-related shenanigans afoot, notably the aforementioned arbitrage. This gave rise to a lot of speculation, in both senses of that word.

Commenting on the spread in Slate, Matt Yglesias surmised that the prediction markets weren't "ready for primetime," since arbitrageurs ought to have corrected the spread in a more liquid market. Others supposed that there was a good reason for this apparent market failure: Republicans were keeping a thumb on the scales at Intrade, maybe through wishful thinking — or, just possibly, because the small size of its U.S. market made manipulating Intrade a far cheaper and more attractive campaign move than buying (more) TV commercials in Ohio.

Anyhoo, it seems a lot of savvy London traders made out like bandits exploiting the Intrade/Betfair arbitrage. I especially enjoyed this report.

After the election, I contacted one of these successful Intrade arbitrageurs; a London hedge fund guy whose name must ever remain a dark secret. (Transcript very lightly edited for clarity and punctuation. And concealment. Let us call him Wallflower.)

MB: How much did you bet on the presidential election?

WF: Not huge amounts. I made about 100GBP arbitraging Intrade vs Betfair, and another 100GBP making directional bets (Obama to win, and a few bets on individual states) on Betfair.

MB: When did you decide to take a flutter, and what events precipitated that decision?

WF: A few days before the election I was reading a story about Nate Silver, who was saying that the election was almost certainly going to go to Obama. I tend not to trust predictions like that unless I can replicate them myself, so on the Sunday before the election I spent a few hours getting some polling data and building a simple prediction model. My model agreed with the 538 [Electoral College votes] prediction — in fact it was even more confident of an Obama win.

[...] I wasn't 100% sure it would work, so I didn't put as much money into it as I could have done - just enough to prove that it could be done and buy a few rounds of drinks with the winnings.

MB: So my understanding is that you guys have had so-called "novelty betting" in the UK like, forever. The difficulties here seem to center round the problems inherent in e.g. too many people knowing outcomes. How come you guys don't have these proscriptions, would you say?

WF: Partly I think there's a more relaxed attitude to gambling in the UK. Though there have been problems, e.g. the recent betting on the next Archbishop of Canterbury — did you see that?

MB: NO that is amazing. So what happened?

WF: So from next year there'll be a new archbishop; there was betting on who it would be. One candidate, Justin Welby, suddenly had a ton of bets placed on him, presumably from people with insider info. You can read about it here..

MB: So I'm wondering if you would take me through your personal concept of the connection between speculation and gambling; in the UK, vs. global markets, US markets, and so on.

WF: OK. I don't think there's any difference between speculation and gambling, really.

[!!!!]

MB: Please comment on Intrade closing down with respect to the following: I understand that like 2/3 of the Intraders were in the US? But it's still a pretty small number of guys. In any case, they've posted their intention to return with a U.S.-friendly platform. Can you speculate as to what that might be? (I can't believe they mean to open a play-money site. No way, after having had a real one.)

WF: I can totally believe that what they were doing was illegal under US law.

By US friendly, it's possible that they mean a platform that allows you to speculate on sports, politics etc but not on commodity prices. There would be zero point to Intrade if it was play money; predictions would be worthless.

There's little chance of ever learning the real motives of Romney fans on Intrade; their motive for placing irrational bets may well have been based on their unfounded hopes, rather than a cynical desire to manipulate the results. Certainly U.S. media reports uniformly indicated that the Republicans were truly convinced they were winning until the last possible instant. When I mooted this with Wallflower, he responded:

"Hanlon's razor in action :)" (That is, "Never attribute to malice that which can adequately be explained by stupidity.")

It's a little sad to think that the American electorate will miss out on seeing our politics spelled out in the prediction markets. These markets are capable of providing a valuable resource; they are often more accurate than ordinary polls, as as Surowiecki and others have pointed out. But come what may, the following characteristic entry on the Intrade bulletin boards just a few weeks ago provided an unusually pithy illustration of the possible cost, in cold, hard cash, of preferring ideology to facts.

Dear dumb-ass Republicans,

God bless you and long may you reject science, statistics, evidence, reality, common sense, and the like.

ps thanks for the money.

yours,

a godless liberal European