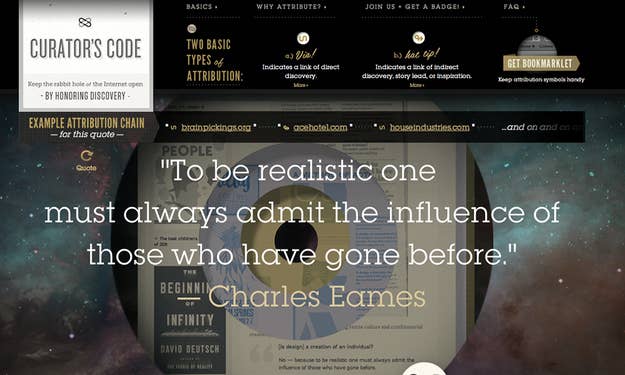

A few weeks ago, the online curator Maria Popova, known on the web as Brainpicker, unveiled a set of guidelines for attribution on the internet called the Curators' Code. The idea was to ensure that online influence itself is traced and attributed: "discovery honored," as Popova puts it. The challenging idea: That "curation" is "a form of authorship."

This proposal has proven surprisingly controversial. Software engineer and blogger Matt Langer best channeled the general indignation of techno-pundits at the idea of "curation" being a form of authorship, roaring: "[P]lease spare the rest of us all this moralizing on why we should be giving people who share links anywhere near the same amount of credit we afford [the] singularly special act of original content creation."

Yet, nobody's writing is worth a thing unless someone reads it. It is a little bit silly to equate Popova's work with "sharing links." The real question is: with whom? The traffic to Popova's website exceeds that of the New York Review of Books, according to Quantcast. There is no question that Popova and others in her line of work don't just bring audience; they also help to shape the public taste. She and others like her go around and learn all this stuff so we don't have to. And the recommendations of Popova, Kottke and all the other popular "curators" of the internet are not for sale — they're motivated by their own taste and curiosity.

To my mind, the Curator's Code was a bit misguided, insofar as it could easily be taken (and was often taken) to be a prescriptive message: "You have to attribute this way" rather than, "It is important to attribute." But I could certainly get behind a movement to acknowledge the democratization of authorship. Criterion Collection founder Bob Stein, who runs the Institute of the Future of the Book, said something to me in an interview nearly a year ago that I still think about all the time: "If the printing press empowered the individual [author], the digital world empowers collaboration." The evidence of this is clearer every day.

And yet, "the good work of others," "original content creation," and traditional notions of "authorship" are all being defended furiously, as if they were the most important part of the transaction. They are very important! But they're one of two essential halves. The salient point here is that those traditional notions of authorship are no longer adequate. They no longer describe the way we create or distribute information in the Internet age.

An essential aspect of the question — the making of an audience, without which no content can be enjoyed, and no writer paid — has gone unnamed in the debate. So where exactly does "curation" come into it? Below is an excerpt of my recent conversation with Popova about the uneasy interface between money, audience and information.

MP: The role of a great editor, curator, whatever we want to call this person is not to give people what they already know they are going to be into; it's to get them interested in things they didn't know they were interested in, until they are. And the cat video is the editorial cop-out. You're not doing your job if you're not broadening someone's horizon. Unless it's Thomas Edison's video of two boxing cats, I don't care about a cat video, and I don't think people should.

MB: Here's the thing, I'm not nearly as high-minded as you.

MP: I don't think I'm high-minded!

MB: Oh, yeah! Like if someone says to me, here is a cat video that a hundred million people have looked at, I am there like a freakin' shot. I still watch Charlie biting his brother. No seriously. Baby Ethan with the tearing paper, I think I've seen that a hundred times. If I'm feeling a little blue, I will go and look at one of those things. So I have such conflicting feelings about it.

In my view if you want to understand the culture you want to be an omnivore, high and low, it should all be grist for your mill. So, while I understand about the cheapening aspects, the so-called lowest common denominator... like, Gawker got everybody in such a tizz with the so-called "traffic whoring." I don't know what the right answer is, but without a doubt I am the one clicking the whore links, for reals.

MP: Gawker is a business. That's the difference; this is such a bigger problem. The catch-all of poor journalism ethics—the root cause of the not attributing, the HuffPostification of headlines, pandering to people's tastes, or slideshows, all these things—is that for the past 120 years we've had the wrong stakeholders for information; those stakeholders have been advertisers, and not the audience. In 1923 a newspaper editor named Bruce Bliven wrote this scathing letter about how the circulation manager had taken over the job of the editor. Until we reinstate the reader as the stakeholder, nothing's going to change. People are going to thrive in these business models that are not doing the audience justice.

MB: But there's really great journalism right now. Shouldn't we be looking toward a balance, rather than trying to force the pendulum to one side or the other? It's clear that in order to pay writers—someone is going to have to pay them, and maybe readers will pay them in the future, that would be great, there are these other models—

MP: Like The Atavist.

MB: Or like The Baffler, where the reader comes first. But look what happened to the Partisan Review, these publications sink into irrelevance because they can't push the circulation out far enough.

There has been so much great stuff on The Awl, for example. They're balancing something, giving a bigger, broader picture of the whole culture, and this does not stop them from publishing beautiful long-form stuff that has absolutely nothing to do with cat videos. So where does that leave us?

MP: This stuff is only possible because they let them get away with it, because they can afford to, because all the other stuff is what generates the revenue. There's some little pocket of experimentation, or being brave. But by and large, there cannot be bravery when you are accountable to an advertiser. My hope is more in models like The Atavist and Byliner, who cut out that middleman and focus on making really great content and a great reading experience that readers can pay for directly, as much as they see value in it.

***

Many, many bloggers new and old have tried and failed to do what brainpicker.org, kottke.org, Daring Fireball and Laughing Squid have done: focus a large audience on a single remixed composition from the web. They are like collagists rather than painters, you might say. Their work is in giving form to the culture through guiding the focus of attention and yes, that is a legit job deserving of both honor and remuneration. It's different from writing (though again, these are excellent writers all).

As it happens we already have a model for this job, which is the profession of the disc jockey. Consider the career of the late John Peel, and the influence of "The Old Grey Whistle Test" on several decades' worth of popular music. Peel's authority, his influence, persists to this day. How much music did John Peel not teach me about? Was I about to listen to all the music that John Peel had to wade through? Would I even have gotten it, if I had? (Let's face it, no, I've spent the last two weeks dancing around in my office to the widely-reviled "Call Me Maybe," b/w Future Islands' "On the Water," clearly I am not to be trusted in this area.)

So people would listen to John Peel if he recommended a band because he proved over and over and over that he could find the one great band out of a million bands, and you could be very nearly certain that you were going to love it. He could talk and write about it all too, with wit and charm.

I told Popova about this idea and she said maybe these "curators" ought to be called IJs, instead, for "info jockey," which would be a lot better. NJs, maybe. "Net jockey." (Or please be my guest to think of a better one.) But let us think of a better name and pronto, something that represents this ability, to focus and guide our attention, in the way we wish it to be guided, so that we can share more and share better.

Let's make a distinction, too, between the NJ and the aggregator, like the Huffington Post. You could make a continuum between Brainpicker at one pole and HuffPo at the other. Brainpicker hopes you'll find her stuff interesting but that hope doesn't influence the composition of her collage, which is obviously and completely personal, the product of an editorial sense all her own. I agree completely, by the way, that this is an authorial act, just like being the editor of a publication is authorial. That's precisely the difference between a "curator" and an aggregator, in fact. The "curator" — I am really kind of starting to like NJ, actually — is making something, a new thing, a publication expressing a particular sensibility, taste, view of the world. An aggregator is just shoving stuff together, anything, anything that will make you click.

You develop an allegiance to a DJ: he speaks to your taste and your way of looking at things. There is something like an ethical component to this, too. You have an affinity with the way that person looks at the world in a lot of different areas. For me the apotheosis of this in the realm of music was the amazing few years that Steve Jones spent "curating" Jonesy's Jukebox on the Los Angeles station Indie 103.1. (The new broadcast on KROQ is a shadow of its former self, alas.) The affinity of Los Angeles with Jonesy, the veteran punk guitarist of The Sex Pistols (it was he in the famous Gumby hat onstage, an unforgettable presence) went far beyond the surprise and glee at finding out how into The Sweet he was. Like his listeners, Jones had been around the tree. His intelligent, hilarious conversation was wide-ranging, encompassing politics, health matters, affairs of the heart. Jones created a nexus of attention embracing a lot of things that people would continue to talk about all over LA. And yes, there was new music, and people would buy records based on Jonesy's recommendations, interviews and so on.

That is what Jason Kottke and Maria Popova (and Paul Ford, and so many, many others) are up to, really. That is to say, I and untold thousands of others will typically see a Kottke post and then comment on it together more than once—not on Kottke's site, but on Twitter, in our own writing, and even in real live conversation with actual people. This is a huge skill, an invaluable skill, to create a context where a story, an idea, a film, a book, can pique all our attention at once.

Being a super special original content creator myself, I value both the aspect of this skill that results in money, i.e. the ability to create Web traffic, and also the aspect that results in the magical, worldwide dialectic that we are all so lucky to be alive right now, so that we can participate in it. When information is shared so widely, it becomes immensely powerful, and might come to have political and cultural effects far beyond the well-bred little ripples of influence that newspapers traditionally engendered (with some rare exceptions.) The Web is still such a new thing, only a few years old. We can't even tell yet where it will lead.

So let‘s not get hung up on antiquated notions of "origination." "Interestingness" isn't the deal, either. Instead let's go ahead and call the "curated" website what it is, a gathering-place, a station, that one may lead but that the rest of us gather in, to enjoy things together, and to share them.