Economists and analysts from banks have joined the chorus of businesses and other financial institutions opposing a yes vote on Scottish independence.

If Scotland votes yes, it will trigger "considerable economic turbulence" in both Scotland and the remaining United Kingdom, a group of analysts from Credit Suisse said in a note Thursday. The bank researchers were echoed Friday by Deutsche Bank's chief economist David Folkers-Landau, who said a yes vote could lead to "negative consequences far beyond what voters and politicians could have imagined" and would "go down in history as a political and economic mistake" as large as the Federal Reserve's failure to support the U.S. banking system at the onset of the Great Depression, which many economists blame for the depth of the economic crisis in the U.S. in the 1930s.

As the polls still show no with a narrow lead before the referendum on Sept. 18, more and more businesses have said they oppose independence or have even threatened to move their legal headquarters from Scotland. The banks Lloyds and Royal Bank of Scotland both said earlier this week that they have contingency plans to move from Edinburgh to London in the case of a yes vote. The disclosure of the plans underline a basic dilemma for Scotland: how dependent it would be on a massive banking industry.

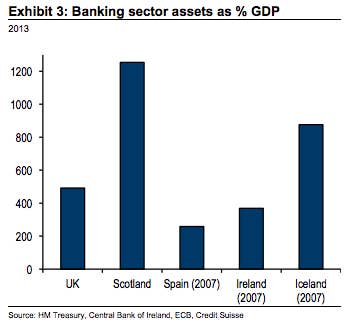

The Scottish financial sector is over 1,200% the size of its economy.

The flow of businesses and money out of Scotland after a yes vote would spark an economic downturn, the Credit Suisse researchers said, because the "environment of much greater political, economic, and financial uncertainty that would follow... would be toxic for business confidence."

Folkerts-Landau put it in more stark terms: "Scottish consumers and investors have benefited from the credibility of the Bank of England's monetary policy, financial institutions and their clients have benefitted from an equally credible supervisory and regulatory regime, while foreign investors come to Scotland because they rely on a predictable investment environment. All of this comes from a united Great Britain."

Scots, Folkerts-Landau further warned, would likely move assets out of the newly formed country "for fear of a forced conversion to a new weaker currency," joining the banks who would flee to London in order to be eligible for assistance from the Bank of England (the British government nationalized both RBS and Lloyds during the financial crisis and still owns significant chunks of both).

And after they change their formal headquarters, Folkers-Landau said, banks would then shrink due to "regulatory and political uncertainty," leading to a smaller construction market and lower employment as lending becomes more scarce. Scottish banking assets account for some 1,254% the size of its economy, according to the U.K. government (although the Scottish government disputes these figures). Credit Suisse estimates that, all told, banking and insurance employ 7% of Scotland's workers and account for 13% of its economic output.

Like other small European countries with outsize financial sectors, the Scottish government could end up having to support its banks in the case of a crisis. That may be hard to do if it introduces a new currency that is pegged at always being equal to one British pound. Because the new monetary authorities would always be primarily concerned about keeping the British pound and the new currency in equal value, it wouldn't be able to create new pounds to support banks, the Credit Suisse analysts say (of course, bank analysts would be concerned with a government's ability to support banks).

Mark Carney, the governor of the Bank of England, said Thursday that other countries, like Hong Kong, with large financial industries and lots of exports tend to have currency reserves greater than 100% of their annual gross domestic product. Carney wrote in a letter to Andrew Tyrie, the chairman of the Treasury Committee, that Hong Kong's reserves are 119% of its GDP, meaning Scotland would need pound reserves of about £145 billion (it would inherit about £15 billion in reserves, Carney said).

"A vote for independence would call into question Scotland's ability to maintain both a viable currency arrangement and the large financial services sector which currently supports a large tax base," the Credit Suisse researchers said. If Scotland were to stay on the pound, it would have to import new pounds by selling more stuff to the rest of the U.K. than it consumes, "depressing domestic demand and crushing growth," Folkerts-Landau said, making the new country even more dependent on volatile prices for oil from the North Sea, which experts have said would run out by 2050.

"The economic and financial arguments against independence are overwhelming," Folkerts-Landau said at the end of his note, which is impassioned by the staid standards of bank research. "But we prefer to conclude by marveling at the three hundred years in which everyone has benefited from Scotland being part of the Union."