Michael Hastings was one of our generation’s best, most driven, and fearless reporters. His work at Rolling Stone changed the course of the American war in Afghanistan. At BuzzFeed, he told the story of the 2012 election and was building a beat on the dark side of Hollywood when he was killed in a car crash at 33, one year ago.

Michael’s obsessive observation, his drive to figure it out, extended to his own profession. In his last years, he became obsessed with the internet, seeing, more so than most of his peers, that it would be a great home for big narratives. But Michael was ready for the change because he had seen the big changes shaking his business up close, watching the death throes of a great print institution as a young reporter for Newsweek from 2003 to 2008. It turns out that he observed that experience with the same obsessiveness and the same reflection.

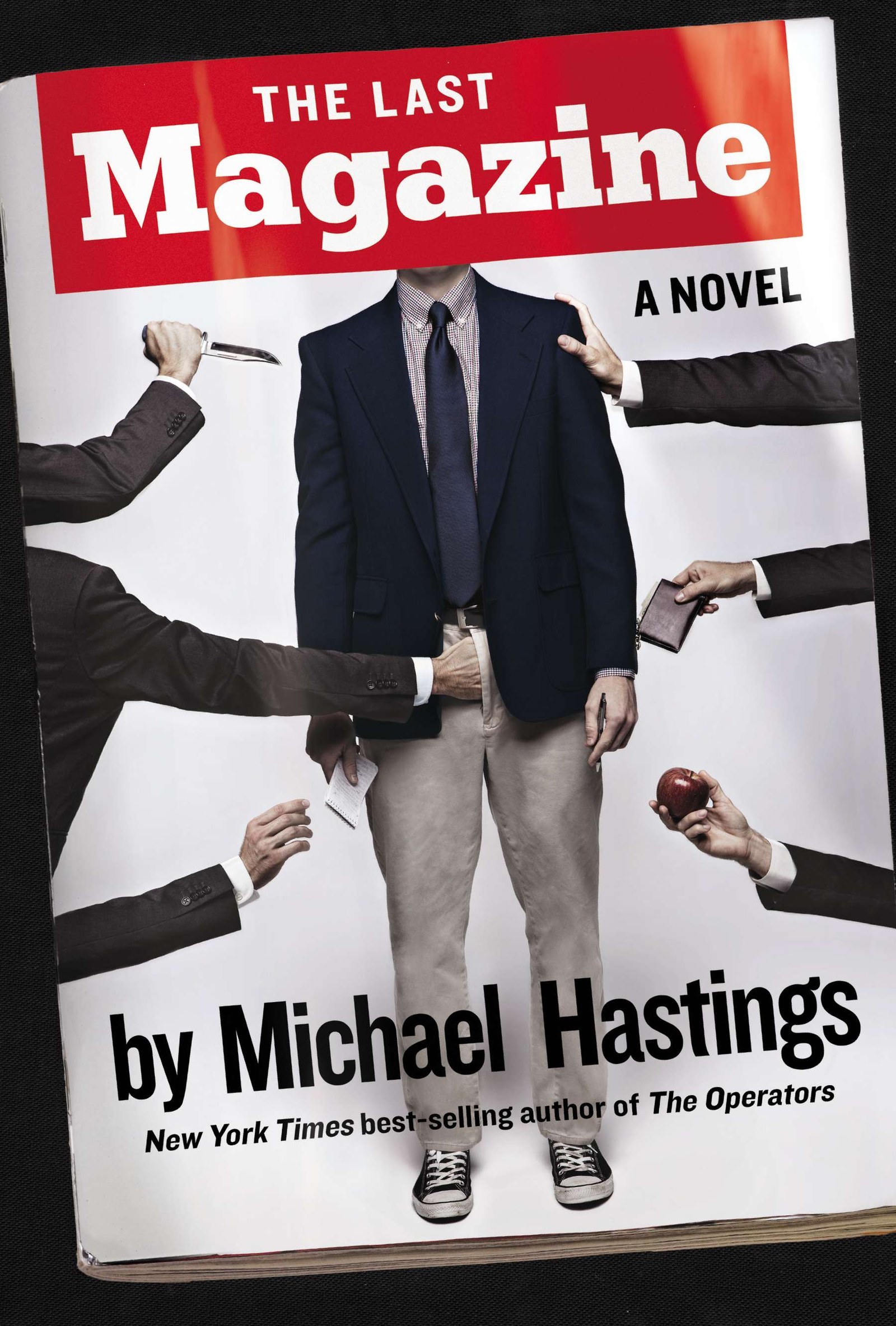

Michael wrote The Last Magazine, his only novel — from which this excerpt is drawn — from that moment. It’s a satire of a thinly fictionalized newsweekly. Its characters will be recognizable to insiders, and most journalists will recognize the strangeness of the collision between raw and urgent reporting from a conflict zone and the comfortable New York institutions that publish it. In these chapters, the young narrator steps back and reflects on his own voice, and then dives back into a story about a war correspondent back from the front and the stuffed shirts running the place. —BEN SMITH

INTERLUDE: TOWARD A MORE CYNICAL PROTAGONIST

I see that I'm setting myself up as the coming-of-age protagonist, a naive and excited twentysomething hero named Michael M. Hastings, unleashed on the world, loose in the big city. Wet behind the earlobes, bright-eyed and puppy-tailed, the universe my own clambake.

But how could I ever have been so naive? How can anyone be naive these days? What's my excuse?

How could I have expected anything else besides what happened? The eventual disillusionment, the disappointment, the subtle corruption. Shouldn't I have seen it coming? If I'm a cliché, shouldn't I have been aware of why I'm a cliché—because my life story, my pattern, has been told and retold over and over again, the future for me was already written? Is it excusable to feel what I eventually feel—betrayed, disappointed, wronged, and upset by how The Magazine treated A.E. Peoria?

Aren't we in a new age? The end of naiveté?

I grew up reading media satires, reading about the corporate culture, massive layoffs, and polluted rivers, reading about censored stories and the national security state, our imperial sins, FBI investigations into masturbation in the executive office, reading Noam Chomsky and Howard Zinn and Tom Wolfe and Pat Buchanan and Hunter S. Thompson—what else could I have expected from The Magazine besides what I saw? I grew up reading Holocaust literature at the beach, Gulag literature on winter holidays, Vietnam memoirs on spring break. Histories of Gentiles and Jews and Germans playing poker and swapping wives at Los Alamos. The rap music I listened to was about dealing crack and dropping Ecstasy and cunnilingus. The television programs and films a constant stream of irony and mocking. How could all of that not have prepared me for the human condition, in the most extreme possible circumstances?

Isn't it somewhat preposterous, looking at the character that I'm presenting to you, for me to feel let down by the world? Isn't that narrative arc just a little tired?

Maybe that's the genius of it, then: because it is tired, it's easily recognizable. You can relate to me. And even with the knowledge of how the world works, we don't really know it until we see how the world works ourselves. Secondhand information doesn't do it.

Until your own hopes and dreams are shattered, or just slightly cracked, shouldn't you be allowed a bit of innocence?

I don't know. Maybe that's the growing-up part. Maybe I was just going through the motions, maybe I knew the fall was coming all along.

Anyway...

I'm going to give my past self a more cynical edge, whether or not I actually had it at the time.

I've taken a week off from the magazine to finish writing this. It's still snowing.

Wednesday Evening, October 23, 2002

The signs are up all over the lobby, in the elevator, in the cafeteria on the twenty-first floor, right outside the elevator doors on the sixteenth. The signs are big blown-up pictures of different scenes from World War II, and every picture—Stalin shaking FDR’s hand, the flag show at Iwo Jima, seven slightly out-of-focus dead bodies floating up to the shore on Omaha Beach—has the big name under it: SANDERS BERMAN.

“You going to this thing?” Gary asks me, leaning up against my cubicle.

“The Berman thing?”

“Yeah.”

“I was thinking about it.”

“I’m going up now, you want to come?”

“Sure.”

I prepared for Sanders Berman’s book party accordingly. I read his book, The Greatest War on Earth. If I am in the mood to be cruel, I’d say his book does really well at nourishing our national myths. It’s a real comfort, reading his book. It gives you a real warm feeling about that whole time between 1939 and 1945. A real black-and-white-photo wholesomeness to it, a breast-fed narrative of good versus evil. A time, thankfully, when there wasn’t much ambiguity. Or at least that’s what he’s selling and that’s what people like to read about, and Sanders does a good job at throwing around words like tragedy and Holocaust and Stalingrad, and does a real good job at making us all feel special about it.

You can say I’m something of a contrarian here, but I guess my reading list on the Second World War is a bit different—more Thin Red Line, memoirs from Auschwitz and Hiroshima, The Battle for Moscow and Life and Fate—stuff that when you read it, you don’t come away feeling particularly enamored with the greatness of human beings and the exceptional nature of the American character. “Fuck my shit,” is how war correspondent Ernie Pyle put it at the time. “That’s what war adds up to.”

So fuck my shit, The Greatest War on Earth reaches number one on the bestseller list, so Berman must be doing something right, and there’s nothing wrong with admiring success. Can’t argue with success, can’t argue with this book party on the twenty-second floor to celebrate the success that he’s having.

“I’m just going to use the restroom,” I tell Gary, using the word restroom because I’m never really comfortable, at work or at home, saying things like “I have to take a piss”—or “a leak” or “drain the lizard” or “shake hands with the wife’s best friend.”

I push open the door to the restroom and hear what sounds like a retching, a hughghghg. The noise stops right when the door is in mid-swing. I can always tell when someone is standing still in his bathroom stall. It’s as if by actively trying not to make a sound, he’s making a silent dog-whistle-like noise that triggers a well-honed lavatory sixth sense—probably a survival instinct from when I was a little kid and public bathrooms were always a potential danger zone, booby-trapped with lurking perverts.

Walking up to the urinal, I glance down at an angle and see the same pair of shoes, pointed to the toilet, not away from it, that I saw a few months back on the night with A.E. Peoria.

I start urinating (or, if you like, I use the urinal, make water, piss, etc.), and it lasts about thirteen seconds. I probably have more left, but I’m a tad nervous with Sanders Berman standing behind the blue panel five feet to my left.

I flush. The man behind the stall f lushes. I zip up; I don’t hear a corresponding zip-up. I turn to take the three steps to the six sinks and six mirrors; the door to the stall opens, and there’s Sanders Berman, taking his own two steps to the sink.

“Mr. Berman,” I say, tapping the pink soap container screwed into the white tile just below the mirror. “On the way to your book party now.”

“I’m running late,” says Sanders Berman, and he’s not so much washing his hands as looking in the mirror and wetting a brown paper towel and wiping his face, primarily around the mouth.

I think it might be best to wait it out, to let the water keep running, to take even more time so he finishes his cleanup first and leaves. Or should I finish washing my hands right now and leave first?

Leave first, I think, but in the seven awkward seconds it takes me to make that decision, Berman has turned off his sink, and we’re both tossing crumpled brown paper towels into the steel wastebasket built into the wall next to the door.

Gary doesn’t act surprised when he sees me coming out of the bathroom with Sanders Berman, and he cracks a joke.

“We’re going up with the right company,” Gary says, and all three of us walk through the glass doors on sixteen. I push the up button on the elevator, and we’re in that waiting time when, really, it’s proper etiquette for Sanders Berman to start asking Gary, a senior editor, questions about how life is going for him, etc.

But with the pressure of having a book party, I guess, Sanders Berman doesn’t fulfill that etiquette duty, and as we step into the elevator, bing, I take up the slack.

“Really enjoyed your book,” I tell him. “I’m a big fan of World War Two.”

“Oh, thank you,” says Berman.

“Hastings is the rising star in international,” Gary says, getting in on the act. “He does great work—if you ever need another researcher, you should ask him.”

Sanders Berman looks at me, nods, and says, “I’ll keep that in mind.”

Mercifully, we’ve arrived on the twenty-second floor, and both Gary and I say, in chorus, “After you,” and Sanders Berman goes first, and Gary and I do what’s proper and just hang back for an almost imperceptible split second so Berman can walk into the room on the twenty-second floor without us.

It’s a good thing we do, because when Sanders Berman enters the dining hall, the crowd gathered inside starts to clap.

Gary and I look at each other—dodged a bullet there.

Book Party, Five Minutes Later

The twenty-second floor is called Top of the Mag. A catered dinner is served to the staff there on Friday nights, the late nights at the magazine. It’s classy, with nonindustrial-strength carpeting and rich, glossy brown-paneled walls. The best part is the view. For that brief moment on Friday, I feel like I’m part of the big time, one of those Captain of the Universe types, with a view of Central Park and Columbus Circle, breathtaking and unmolested greenery all the way to Harlem.

It’s also where the magazine hosts events like this one.

Framed posters of Sanders Berman books are up on the wall, with pictures that I have seen before in history books but not pictures that I’ve seen in the context of the promotion of his book—the USS Arizona going down in Pearl Harbor, VJ-Day in Times Square, Churchill on some podium.

Gary and I head to the bar, something to do, and I get a club soda and he gets a Coke.

“You owe me one,” says Gary.

“Thanks. No, that would be great, doing research for him.”

“It’d be a real feather in your cap.”

Gary often talks to me about feathers in my cap. Now, it isn’t about the good of the magazine that Gary tells me to get as many feathers in my cap as possible—because I don’t know anyone who hates the magazine as much as Gary does. He hates it, really detests it. Thinks it’s a total piece of shit. “You don’t think I don’t think about quitting this fucking place every day of my life,” he told me last week. “You don’t have a mortgage, you don’t have kids, you don’t have responsibility, just walking around, the change jingling in your pocket”—he likes to tell me that, that I walk around with change jingling. But we do get along, and he wants to help me out in my career as much as he can, by assigning me that Space Tourism story, for example, or by putting a good word in for me with a guy like Sanders Berman.

Gary and I stand next to each other, sipping our nonalcoholic beverages, watching other people socialize.

There are some noticeable absences. Where’s Henry the EIC? Nishant Patel? Every other bigwig is here, including Tabby Doling, the daughter of The Magazine’s owner, Sandra Doling, who, when she was alive, also owned a big newspaper in Washington and nineteen other media properties around the country, including local television and radio stations.

“That’s Berman’s source of power,” Gary whispers to me, talking about Tabby Doling. “Her mom is the one who discovered him. Way back in the early nineties. I think he was still in school. She put that story of his, the famous one he did…”

“The ‘Vietnam Syndrome’?”

“Yeah, that’s the one. She put that story on the cover.”

At that moment, a semicircle of people starts to form, the employees and famous and semi-famous guests (Kissinger, Stephanopoulos, Brokaw, etc.) step away, leaving Sanders Berman, Tabby Doling, and Delray M. Milius in the center. Milius holds up his glass and taps it, chinking and bringing silence to the room.

Delray M. Milius is doughy-faced and five-foot-seven, and I don’t mention his height pejoratively, as I’m only five-foot-nine, and I’ve never put much stock in how tall somebody is in relation to their character. I know big pricks and little pricks, as I’m sure we all do. He’s Sanders Berman’s right-hand man, his hatchet man, if you will, or if you believe the story—and I believe it because it’s true—he’s “that glory hole ass gape cocksucker.” I don’t choose those words lightly, or to offend homosexuals, some of whom are my closest friends, but because those were the words that Matt Healy, a correspondent in the magazine’s Washington, D.C., bureau, put in an email, accidentally cc’ing the entire editorial staff. This was back in ’99, before my time, and when email mistakes like that were more common. It was also back when Healy was in New York. After that email, he was sent to D.C. in a kind of exile, while Delray M. Milius leveraged the potential sexual harassment suit to get a big promotion to assistant managing editor, where he’s twisted Sanders Berman’s bow tie ever since.

As you can probably guess, Milius isn’t too popular at the magazine. There’s a strong anti-Milius faction, and within this faction, there’s always a running bet about how long Milius is going to last—this time. He’s left and come back to the magazine five times in twelve years. “Don’t let Milius bother you” is the conventional wisdom in how to deal with him. “It’s just a matter of time before he wakes up one morning and just can’t get out of bed and quits again. Paralyzed. By depression, fear, anxiety, who knows—it’s happened before.”

Delray M. Milius keeps tapping the glass.

“Thanks, everyone, for coming to Sanders Berman’s celebration,” Milius says. “I especially would like to thank our esteemed guests. Without going on, it is of course, and has always been, an honor to work with Sanders, and those of you who know him know that this success is the perfectly natural result we would have expected. But without going on, Tabby Doling would like to say a few words.”

Tabby Doling is bone-thin, rail-like, brown hair held in a pretty coiffure. She’s maybe sixty.

“When my mother first met Sanders, he was a senior at Tulane, and she was there on a speaking engagement. What, Sanders, you were still in seminary studies?” she says.

“God and war, my two favorite subjects,” Sanders says. Everyone in the room gives a nice and expected laugh.

“Sanders is a prize, and I’m very pleased so many of us are here to recognize this, especially my guests—”

Notice the word my. Tabby Doling’s thing is that she’s friends with a bunch of famous and important people, media types, heads of state, Academy Award winners from the ’70s. Though she’s partial owner of The Magazine’s parent company, on the masthead she’s listed as “Special Diplomatic Correspondent,” which is kind of a joke, because that would lead readers to assume there are people above her in the hierarchy, which there are not—she even has a floor to herself, the notorious twenty-third floor.

Tabby is one of those people who, if you bring up her name in conversation around New York, you’ll most likely get three or four really great anecdotes about. Everyone who’s met her has a moment to recount, told with the bemused acceptance that if you’re that rich and that eccentric, it’s par for the course. Gary’s Tabby Doling story, for instance, is that he was standing in the hallway on the sixteenth floor when he heard a knocking on the glass; someone had forgotten their ID. When Gary went to answer it, he saw Tabby through the glass and decided to make one of his customary jokes. “How do I know you’re not a terrorist?” he said, as if he wasn’t going to let her in. And she responded, “I’m Tabby Doling,” with a real flourish and emphasis on both her first and last names. Gary thinks that’s why he got passed over for the domestic sci/tech gig and has been stuck in international. That’s a pretty low-level story, too, not one of her best.

I don’t know her at all and haven’t spent time with her, which isn’t surprising, as she has a $225,000-sticker-price Bentley and a driver I always see idling outside the entrance on Broadway for her—though she did say hello to me in the hallway once, so in my book that’s a plus. She keeps talking about what a wonderful man Sanders Berman is, and everyone agrees and claps and laughs when appropriate.

I’m looking over the room, and I notice that most of the people look more or less like they’re up here for a reason—because they’re supposed to be—or are here because they’re the kind of name that goes in a New York gossip column, which is great for Sanders Berman’s book, because the gossip items, whatever they will say, will also mention The Greatest War on Earth. I’m not telling you anything groundbreaking or new, but it’s good to explain a few things every once in a while.

There is one guest, a man, I’d say sixtyish, who would stand out less if he weren’t planted back in the corner against the glossy brown paneling. I’ve never seen him before, which isn’t that unusual, but he’s wearing a baseball cap—the baseball cap says “POW/MIA,” and so I think, If he’s wearing a baseball cap, he probably works in the mailroom.

Sanders Berman starts to speak, a perfunctory address, and the book party—and the “party” part of book party is a bit of an overstatement, as there’s not really much partying; a more accurate phrase would be something like “mandatory book gathering”—starts again.

The guy with POW/MIA is still planted there, and I end up next to him.

“How long have you been with The Magazine?” I ask.

“Not with the magazine, son,” he says with a southern drawl. “That’s my boy up there.”

“You’re Mr. Berman’s father,” I say, for lack of anything better. “That’s right.”

Times like this are when it really pays off for having done so much research and reading about my colleagues. I did get around to reading the “Vietnam Syndrome” story, and in it there’s a reference, in, like, the sixteenth paragraph, to Sanders Berman’s father, a “Vietnam veteran.” It stood out because Sanders Berman is never one to write about his personal life; I think that’s the only reference to his personal life I’ve seen.

“That’s great that you could make it up to New York,” I say.

“He didn’t ask me here. I don’t think that boy wants me here. I’m here because I’m trying to save him,” he says.

“Right, of course,” I say.

“Did you know that Sanders, and that other one, Nishant Patel, are members of the Council on Foreign Relations?”

“That’s right, I did know that.”

“Did you know that Tabby Doling’s mother, Sandra Doling, used to meet every year in Germany, a little something called the Bilderberg Group. Freemasonry, you know?”

“Yeah, I’ve heard of the Bilderberg Group.”

“What does that tell you?”

What it tells me is that rich people like to hang out with rich people, and that guys who fancy themselves foreign policy experts like to hang out and talk about foreign policy, but I know he’s looking for a more History Channel “Conspiracy Revealed” insight. The problem with talking conspiracies is like the problem with talking religion: you’re either preaching to the choir or arguing with the inconvincible.

“You were in Vietnam,” I say.

“I was. Phoenix Project. Air America. Blackest of black ops. Over the border, Cambodia, Laos. I drink because of it. I’m angry because of it. I killed people, and I don’t say they were innocent—no one is innocent in this fallen paradise. I always told Sanders that killing and war are man’s most horrible things, the most deadliest things. I will admit that it takes a lot of courage to kill like I have killed, and I made that clear to Sanders, but now here he is, hobnobbing with the Illuminatos.”

“Illuminati?”

“Illuminatos, more than one. Hispanics influence nowadays. You know, Davos?”

“I see what you mean. So, you’re from the South?”

“Rolling hills, bootlegging country, hollows. I haven’t set my eyes on the boy in years, he doesn’t visit much, but I tried to teach him as best I could. We’re right near Chickamauga, and every weekend I would take Sanders out and let him loose, to teach him what it means to be afraid for your life, dress him in camo from the Army/ Navy, face paint, and we’d play the special ops kind of hide-and-seek. He teethed on the KA‑BAR. I think I failed, though. Look at him now.”

I’m no Jungian, but the thought does occur to me that Sanders’s loving embrace of Apple Pie and all that starts to make more sense after meeting his father and getting a glimpse of the kind of twisted upbringing in the American dream he was apparently subjected to. Rebelling in reverse—growing up under the PTSD fringe, when he was bombarded with all sorts of ideas about the bullshittingness of our national myths, it makes sense that he’d want to immerse himself in national myths, and in fact, start to believe in the exact opposite of what his father told him.

I’m sort of looking for a way out of this conversation when I see A. E. Peoria walk in, head straight to the bar, and say loudly, “No shots? Wine only?” And as Papa Berman keeps a running commentary on the insidious nature of his son’s current endeavors—The Greatest War on Earth is published by Simon & Schuster, SS, the name of the elite Nazi unit, and Simon & Schuster is owned by CBS, and “CBS” backward is “SBC,” and “SBC,” in Greek letters, is the exact same sequence of letters engraved on the inside brass door knocker at the secret society, you guessed it, Skull and Bones, on the Yale campus in New Haven, the location of an underreported 1913 meeting where J.P. Morgan and some Jewish guy devised the illegal income tax—A. E. Peoria breaches etiquette by bumping up next to Tom Brokaw and Henry Kissinger, who is short, no comment, and they are talking to Sanders Berman and Tabby Doling, and even from thirteen feet away I can hear what he’s saying—“Chad…Penthouse letters…where do you think I should go next?”

For five minutes Peoria stands there, before abruptly twirling around and leaving from where he came, and I hear Sanders Berman say, semi-uncomfortably, “That’s a magazine foreign correspondent for you,” and they all laugh at Peoria’s expense.

By this time, I’m swept back toward Gary, and I ask him, “Did you see Peoria?”

“That was ugly,” Gary says.

“Yeah, I think he was pretty drunk,” I say.

“Hastings, you have ambitions to be a foreign correspondent, right? Just remember, really, do you want to end up like Peoria? I mean, he’s a cool guy and all, don’t get me wrong—but he doesn’t have a home or a family or anything, and there’ll come a time when you’ll have to ask yourself, do you want to end up like that?”

Reprinted with permission from the Wylie Agency and Blue Rider Press, a member of Penguin Group USA Inc. Copyright © 2014 the Estate of Michael Hastings