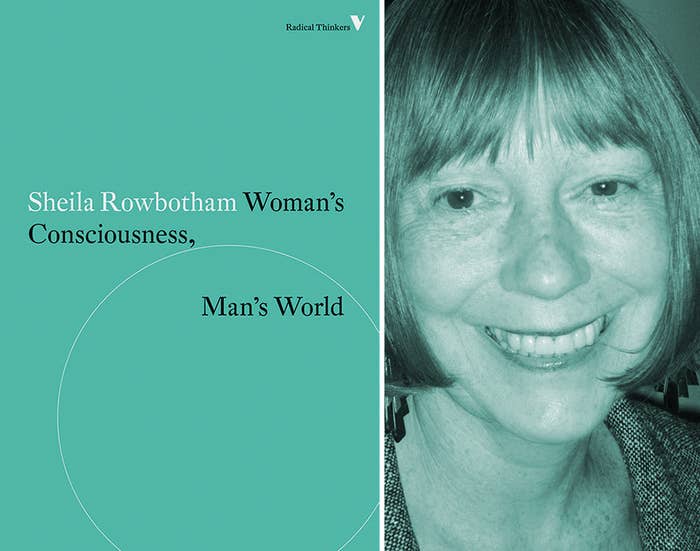

Forty years before Sheryl Sandberg's Lean In, there was Sheila Rowbotham's Woman's Consciousness, Man's World.

Hailed by Simone de Beauvoir as one of the most interesting feminist thinkers of her era, Rowbotham didn't always think of herself as a feminist. Growing up in 1950s England, she associated the word with "frightening people in tweed suits with stern buns," but she was always countercultural, drawn first to the bohemia of the Beat movement, and later to the moral certainty of Marxism.

Within these movements, Rowbotham began to think critically about her experience as a woman. She reeled at the socialist men who "solemnly told everyone that drugs and drink and women were a capitalist plot to seduce the workers from Marxism," and the passivity of the ideal Beatnik "chick," who was "serene and spiritual … with a baby on her breast and her tarot cards on her knee." But she also felt a sense of solidarity with the women she encountered, from girls "with no academic protections" who earned their financial independence by dancing in clubs, to Beat women who organized "co-operative sewing schemes" for artists. "They weren't like me," she writes in Woman's Consciousness, Man's World. "But they were enough like me in a different way for me to respect what they were doing."

By the end of the 1960s, both the U.S. and British Left were in a state of fractious expansion, as the burgeoning black power and women's liberation movements demanded a new politics that took into account identity and difference. Rowbotham was at the forefront, co-organizing the landmark National Women's Liberation Conference, held at Oxford in 1970.

In Woman's Consciousness, Man's World, first published in 1973 and re-released by Verso books last month, Rowbotham brings her feminism and socialism together, arguing that capitalism shapes and upholds the gender divide: Men's earning power depends on having someone, typically a woman, do a whole lot of unpaid work in the home. (In recent decades, that housework and child care is increasingly done by immigrant women and women of color for low wages.)

Rowbotham's critique of capitalism is scathing, but she also acknowledges that capitalism provided the conditions for second wave feminism to emerge. Liberating technologies like the Pill — and the capitalist philosophy of the self-actualized individual — enabled women and children to be seen as people with their own rights and desires beyond the family unit.

In an age of #GirlBosses chasing a vision of success defined by men who relied on the support of stay-at-home wives, Rowbotham's arguments feel both provocative and immediate, calling into question some of the sacred cows of 21st-century pop feminism. So I called three of my favorite young feminist writers, Laurie Penny, Reni Eddo-Lodge, and Jacob Tobia, to talk about what we might learn from Rowbotham's work today — from the new wave of feminist consciousness raised (sometimes painfully) over social media, to the problem with measuring gender equality in the bank account balances of America's richest women.

—Rachel Hills

Reni Eddo-Lodge (London journalist on race, gender, and social justice): One thing that Rowbotham talks about in the book is the development of a new feminist consciousness that was happening in the early 1970s. She says, "Now we are like babes thrashing around in darkness and unexplored space. The creation of an alternative world and an alternative culture cannot be the work of a day … theoretical consistency is difficult, often it comes out as dogmatism." It reminded me of some of the battles going on in feminism as the moment. It feels like a lot of kinks and creases and sticking points are being painfully ironed out and tugged at, in a massive community of people who have different ideas about what it means to imagine a better future, even though they are all broadly left of center. Currently, some U.K. feminists are trying to have a debate on trans people's right to exist, which is very disturbing.

Jacob Tobia (genderqueer media maker and LGBT business consultant): There are times when I think that the internet has made the sticking points of feminism (i.e., trans issues, racial justice, pro-sex vs. anti-sex, etc.) much stickier, as the controversy around Patricia Arquette's comments at the Oscars demonstrates. Arquette used her Oscars speech to advocate on behalf of wage equality for women, later adding that "it's time for all the women in America and all the men that love women, and all the gay people and all the people of color that we've all fought for to fight for us now." The feminist blogosphere erupted with voices telling Arquette where she got it wrong — that women of color and LGBT people have been fighting for women's equality for generations.

Rachel Hills (feminist journalist, author of The Sex Myth): Yes. I'm still on the fence on whether fourth-wave feminism is a "thing," but if it is, I think it is characterized mainly by a diversification of the types of stories and experiences we hear about when we talk about what it means to be a "woman." White, middle-class cis women (like me) don't get to hog the microphone anymore. That's tremendously exciting in terms of the conversations we're having with each other, but it also means that there are a lot of arguments happening about what it means to be a "good feminist." If there are competing versions of reality, it is because we are all living different realities. Take the recent dust-up over Jessica Williams' disinterest in taking Jon Stewart's hosting job at The Daily Show. It is true that many women experience a lack of confidence that makes them less likely to put themselves forward for jobs they are perfectly qualified for. But while that might be true in the general, it was not true in the case of Jessica Williams, and the assumption that she didn't know her own ambitions was misplaced.

Reni: We live with a lot of contradictions. Sometimes I think life would be easier if I were a status quo-loving Tory.

Laurie Penny (author, journalist, Nieman fellow at Harvard University): I think within feminism, as within nerd culture, a lot of the pain comes from the feeling that you are already part of a special circle of people who feel marginalized, and feel like they're creating an alternative community. To have someone then come into that group and tell you that that you yourself are engaged in marginalization and exclusion, that creates existential crisis. It's profoundly upsetting.

Reni: So, what does this mean for the "new consciousness," as Sheila calls it? I would like to see the better future we're all imagining to be open minded rather than falling into dogmatism.

Jacob: I think that in order to get there, we have to change the ways that we engage with one another online. We have to find ways to be more considerate and constructive in our feedback if we are to really build a new feminist consciousness of any sort. When feminists yell at each other IRL, sometimes that can be productive. But when we yell at each other online, I rarely find that it's working toward a new collective consciousness.

Rachel: Laurie, I want to go back to a point that you made at the beginning of our conversation. You said, "I feel like the discussion of labor, what does and does not constitute labor and how it should be divided, are the great taboo in modern feminist thought."

Laurie: So, right from the start Rowbotham challenges the notion that liberation means shoehorning more women into male modes of production.

Jacob: Yes! And that is so important!

Laurie: The idea that "equal pay" is where it starts and ends is kinda where mainstream feminism ended up in the 1990s. You've got the right to be equally exploited, now shut up and get to work. It's no accident that this idea is just starting to be challenged again right now as a new generation is discovering that work does not equal liberation.

Jacob: I think that feminism has lost that sense, at least in a mainstream cultural capacity. Mainstream cultural feminism is epitomized in demands for equal pay, for the ability to "play like the boys."

Laurie: I think the challenge to "work" itself is the most radical thing in this book.

Rachel: Yes, as a non-Marxist I found it very eye-opening. In particular, how she talks about labor under capitalism in terms of exchanging your LIFE for money. At one point she writes, "The money represents the measure of the time and possibility which has been subtracted from his life. Time is the measure of what he has lost, money represents the measure of what he is allowed." It's powerful stuff.

Jacob: I think what we've seen in recent years is a real constriction of the imagination of mainstream feminism. Mainstream feminism means becoming Oprah, Beyoncé, or Sheryl Sandberg — the accumulation of wealth is how you demonstrate your equality.

Reni: Don't get me wrong. It costs money just to stand still these days. I can understand why those of us who don't have much money dream of it setting us free.

Jacob: I love Beyoncé and Oprah as much as anyone else, but they only represent one vein of feminist thought and analysis, and that type of feminism has definitely been elevated in pop culture over other, more politically challenging forms of feminism.

Rachel: How do you think feminism could incorporate a better class analysis? And what is stopping us from doing that? Is it just that class isn't sexy? Or perhaps more pertinently, not profitable?

Jacob: It doesn't work with the "keeping up with the men" mentality of modern pop feminism.

Laurie: It's partly about who gets to speak and define the conversation. Mainstream feminist discussion has been dominated by wealthy white Western women, mainly straight and cis, who are financially secure and who are able to employ less privileged women to do menial work on their behalf, talking about those parts of gender oppression which affect them. (And those issues are important too.) But class is actually part of the root gender oppression, so it affects everyone, including the 1%.

Reni: I wrote an article a few months back about the domestic labor gender divide. Women are still doing twice as much housework as men, shouldering the majority of a shared burden. The response I got reminded me that housework as a feminist issue doesn't get much airtime.

Jacob: I think what is really interesting is that we are in some ways replacing what used to be a gendered divide between workers and homemakers with a class-race divide between business people and domestic workers. Like, modern women who are "equal" to men and are able to maintain families and such often do so at the expense of other low-wage workers of color raising their children and cleaning their homes.

Laurie: Yes. That's the entire message of "having it all" feminism. Lean In is predicated on the notion that you'll also be leaning ON immigrant women, women of color, and poor women.

Rachel: Does domestic work HAVE to be a shitty job, or is the problem just that it's not valued in our society?

Reni: It's just not valued. Cis men still aren't taught that keeping the home they live in clean and livable is their responsibility.

Jacob: And not only are they taught that it's not their responsibility. They're also taught that it's not VALUABLE. They're taught that it is silly, unimportant work.

Reni: YES, Jacob. One good thing that Sheila says in the book is how husbands return home and see all the housework that hasn't been done.

Rachel: What is the solution here? Is it to pay domestic workers more money? To get men to do more domestic work so that it doesn't need to be bought and sold?

Laurie: I'd say universal basic income, socialized medicine and child care, and a complete re-evaluation of what constitutes labor. As a list of preliminary demands. I think it's also going to involve talking about misery. About depression and exhaustion and how shitty it is to have to earn money. Talking about anger and depression is not sexy feminism, but it is important.

Reni: I often imagine what a world without compulsory work would look like. I still can't conceptualise it.

Rachel: True, but non-sexy feminism has been put on the agenda before. Domestic violence is not at all sexy, but it is a big media issue in Australia at the moment, where I grew up, and that's mostly down to one writer, Clementine Ford, writing about it again and again and again. Rape culture involves sex, technically, but it's not sexy either — and it's a massive part of the feminist agenda now.

Laurie: Hey, I happen to think total reorganization of the wage labor system is sexy as hell.