A few years ago, I was talking about art with a friend — a particular artist had infuriated me by not putting his work online, and his gallery refused to post images of it online, either. My friend turned pale and made a weird noise. "Of course good galleries don't put their collections on the internet!" he said, "That's not the way it works." He looked stunned that I would even suggest such a thing. In the fine art world, an artist needs to be represented by the right gallery to have access to right collectors, who in turn get to have access to the artist.

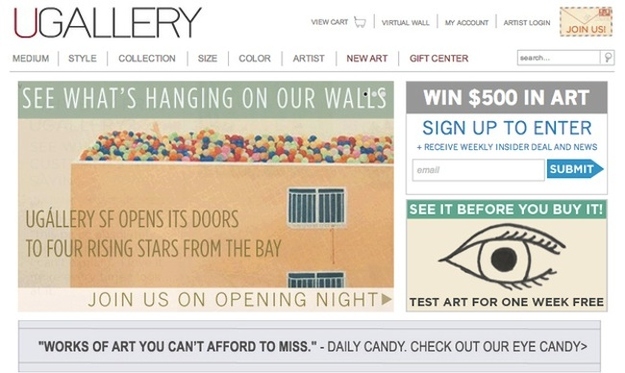

But that system is changing: Art.sy, the biggest and splashiest attempt to wrangle the art world, online, launched a few weeks ago, following similar efforts like VIP Art (online art fair), Google Art Project (indexing of art work from the search giant) and UGallery (online art gallery). Art.sy is distinguished by its cool investors (like Jack Dorsey of Square and Wendi Murdoch, wife of Rupert) and credentialed advisors (Russian art empress Dasha Zhukova; the former chief curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art) as well as its "Art Genome" discovery engine designed to break down elements of artistic endeavors into tiny parts, à la Pandora.

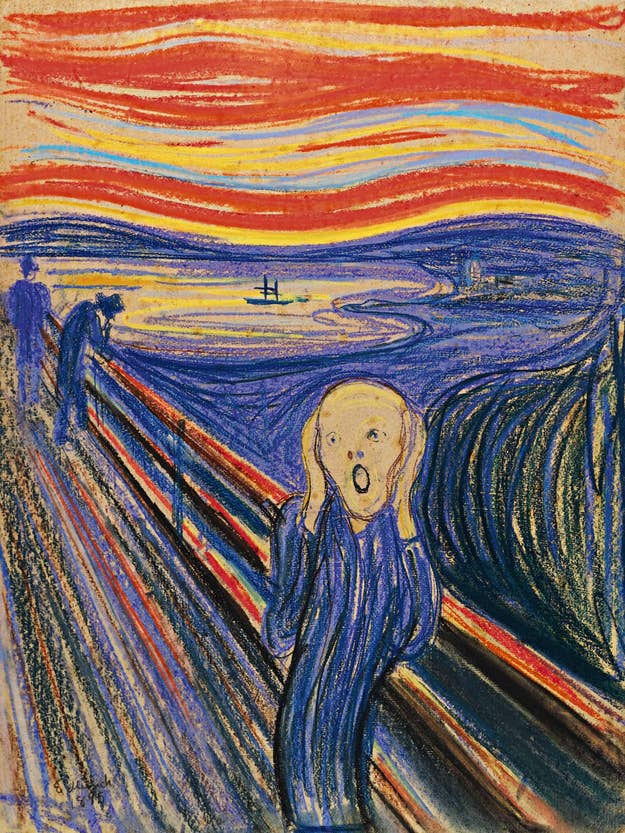

With categories like "Street Art" and "Undifferentiated Abstraction," viewers can browse through 20,000 works of art drawn from a number of participating museums and galleries. This project has been in beta for a few years, so there are around 60,000 users signed up already.

As much as Art.sy offers, it's telling what the site lacks: a platform for artists to communicate (and sell) their work directly to an online audience. While there are numerous online arts and craft-based marketplaces, like Etsy or 20x200, a site to buy prints, the fine art world has been largely insulated from the disruptive forces that have shaken up music and publishing, and forced traditional gatekeepers to change direction. Self-publishing, self-promotion, recording songs on your computer and distributing them on websites — there's not really an art world equivalent for those behaviors.

But Art.sy and VIP Art don't want to cut the galleries and museums out of the equation at all — and neither do many artists, who depend on their services. But if art can't be like music or publishing (and record labels and publishing houses still exist there, too), what will it be like? As the world goes digital, art will have to adapt, at least in part, to the new realities or risk obscurity. Not the good, cool kid kind, either: already, art attendance has been on a decline for a number of years. If consuming art always requires someone leaving their house, that's a problem.

Art.sy, though, was not dreamed up by a frustrated museum worker. Its founder is a 26-year-old guy named Carter Cleveland, who came up with the concept in his Princeton University dorm room, said company COO Sebastian Cwilich. The company sees its launch as the beginning of a "long term play" to harness the growth in online art sales. That itself is a difficult thing to quantify, as "online" can be anything from a long-term collector buying a piece based on an exchange of JPEGs to someone clicking on an Etsy store.

"Increasingly, as people recognize that the art market is global, dealers and museums see that online is going to be an important way of reaching growing numbers of people," Cwilich said. "It's going to take some time, be a process. Different ends of the market have different levels of comfort [with the internet]."

A stroll through the site reveals a nice interface and interesting categorization of art. The team behind Art.sy consulted with art experts to create 800 "genes": when I clicked on a Keith Haring picture of a tea set, the related images ranged from a Fabergé egg to a Basquiat painting. Unfortunately, the number of images still means that you reach the end of a category fairly quickly — Google Art Project has around double the offerings of Art.sy. And as Alan Bamburger, an appraiser and founder of Art Business website, points out, art is fundamentally different than music in terms of ability to categorize.

"The problem is, with Pandora, you can have a band or a group that, in their entire lifetime, might produce 300 songs," Bamburger said. "How about an artist who produces 50,000 images in their lifetime? Or 2,000? Each different work can be a different type of art."

The discovery mechanism, though, is only part of the site's function. Its business model requires buying work, not just browsing: Art.sy hopes to facilitate interactions between galleries and collectors and then take a cut when work sells. A participating gallery or museum has access to extensive analytics and a back-end content management system for free — Art.sy's only money-making feature is taking a cut of sales they help facilitate. The site is betting on a future where people interested in art can go from browsing to buying with a few clicks: if you want to inquire about buying one of the roughly 10,000 works for sale, priced up to $1 million, you get directed to a "specialist" who will guide you through an interaction with the gallery. Art.sy collects a 3% fee from the gallery should that interaction result in a transaction.

"Quite a few artists who cultivated their profiles onine, by selling art on eBay, or by getting covered on various art websites. The same opportunities are now available for artists as are musicians to present their work to huge audiences," said Bamburger.

But career development is a fundamentally different process for most visual artists. With art, the gallery that represents you does a lot more than broker sales of your work: it defines your existence in the market. "If you're represented by Gagosian or one of the other main galleries, you have a pedigree that no other artists has, besides someone else at the gallery, and that's not going to change," Bamburger said.

Even some of the most untraditional artists follow the rules. While perusing Art.sy, I spotted two drawings by Tom Marioni. He's a Bay Area conceptual artist, known for performance installations like "The Act of Drinking Beer with Friends Is the Highest Form of Art," which is pretty much what it sounds like. When I contacted him for this story, he said he had never heard of Art.sy and didn't know why his drawings were on the site. (The website said it had the permission of the gallery but if he or any artist wanted their images off the site, it would remove them.) As someone whose work is "I don't know, esoteric," he said he does not have a lot of moneyed collectors — but he added that he would never sell his work directly to customers, online or off. As untraditional as he is, the gallery model still works for him.

"I don't know many artists that successful at all who don't have a gallery representing them," Marioni said. "You're not going to buy something online for $100,000. You just wouldn't spend that on something that you saw on a website."

But Art.sy and similarly minded VIP Art are making a long-term bet that this mentality will change. VIP Art began in 2010 as a virtual art fair, a way for galleries to avoid the hassle and expense of carting their goods to another art fair, which have sprung up like locusts in recent years and can cost upwards of $30,000 to attend. Its first outing was a bit of a disaster: respected galleries, lured by the lovely design, signed up to participate but the actual website was wonky and kept going down. Now, they have rebranded themselves as more of a general marketplace and VIP, like Art.sy, is firm in their conviction that they don't want to replace galleries so much as work with them.

"Right now, the internet has not replaced anything," VIP's Associate Marketing Manager Evelyn Kroenlein said, "People use it as a way to browse, to look through a catalog, and learn about art."

Even UGallery, an online art concern based in San Francisco, isn't trying to disrupt the actual gallery system. Representing about 500 artists, they just moved headquarters online from brick-and-mortar — when they display an artists' work, like any gallery, they ask for exclusive rights to sell it.

But for the average human, who takes one look at the terrifying "gallery girls" sitting in front of white-walled art spaces and heads for the door, Art.sy and its ilk offer the potential of seeing and even buying work without having an art history doctorate or knowing Lena Dunham's mother. The move to digital is something that art institutions at all levels are grappling with, with museums often at the forefront. San Francisco Modern Museum of Art, for instance, has been lauded for its particularly savvy web approach. Its Twitter feed has over 350,000 followers and its Open Space blog is widely read around the art world. Like many museums, SFMOMA has bulked up its live event calendar as well as its online offerings — to neglect either would be risking irrevelency at a time when traditional non-profit funding models are imperiled by a bad economy and aging patrons.

And Chad Coerver, the head of Content Strategy and Digital Engagement for SFMOMA, was not shy about talking about the difficulties in rendering art online. "We can't be Pandora because there is still an object back there," he said, "The thing that makes art world difficult, the last nut to crack, the object. Even in a book, without pictures, ultimately you're still reading the same product."

"This is why you still need museums, why do you need galleries — you need places to show the work, maintain the inventory and cash flow," Coerver said, "We still have these huge roles as the keepers of the physical thing. You do everything you can in the digital space, but in the end, you still want your artwork, you still want to have a face-to-face encounter." The art remains the thing.