Imagine that you're a river otter at the Oakland Zoo. Until recently, the chances that you would have babies was very slim. While a female otter, Ginger, came to the zoo in 2009, it took two years for her first set of pups to be born: before then, the Oakland Zoo had not seen a newborn river otter in its tanks in over a decade. This isn't rare in the captive-river-otter world: according to a San Francisco Chronicle story, only a handful were born in North America this past year. Also, otters don't give birth nearly as many times in their lifetime as fast-replicating creatures like, say, insects: the pregnancy period is unusually long — it takes months after mating for an embryo to lodge itself in the uterus and often a full year for birth to happen.

But last February, two river otter pups, Tallulah and Ahanu, beat the odds. Almost exactly a year later, three more pups were born. What happened? It wasn't a pair of Oakland otters hitting it off. Like so many of us nowadays, these otters' mom and dad met digitally.

Every animal born in an accredited zoo in the U.S. has a complicated data network behind it — from behavior to genetics to location, at least three different software applications track over 600 species. 55% of those species' populations are deemed "imperiled"—a fact that motivates the four full-time employees of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums' Population Management Center (PMC) who manage digital "studbooks" and reproduction-info web pages for thousands of individual animals, ranging from lizards to tigers to birds to rhinos.

So it's like Match.com for animals? "Sort of," laughed Sarah Long, director of the Chicago-based PMC, "They don't have photos, though." Long has been overseeing the love lives (if you will) of the nation's zoo animals for the last decade. While historically zoos have been more about entertainment than science (and some argue that their existence is still basically immoral), their function has undergone great change in the past 30 years, in the process creating jobs like Long's.

Recognizing that many of the world's species are threatened by extinction, accredited American zoos banded together in 1981 to start a captive breeding program, the Species Survival Plan, that would treat the whole country like one big mating pool. Information was collected about pedigrees to discourage inbreeding. In 2000, the AZA opened up the PMC to oversee population programming. Building off of an original database that was, essentially, spreadsheets, the center has been has added "bells and whistles" over the past few years, like the aforementioned profile pages, to help expedite the process of matching mates.

Visualization options are the latest innovations of the new PMC software ("PMx"), released last year. Using techniques borrowed from insurance actuary tables, PMx can take information on average life expectancies and birth and infant mortality rates and create a demographic profile of breeds and individual animals. The weaker the results, the more incentive zoos have to breed their stock.

Once the need to breed has been established, pedigree data comes into play. "That's when 'Match.com' computer dating comes in. We'll look at who has the most valuable males and females and try to get them together as long as they are not related to each other," said Long.

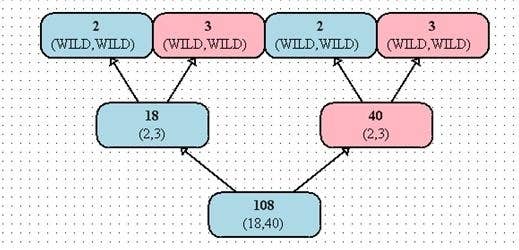

Here's the animal equivalent of a profile picture: a screenshot of the family tree of an animal, identified through its ID number (#108) and its parents numbers (father is #18, mother is #40).

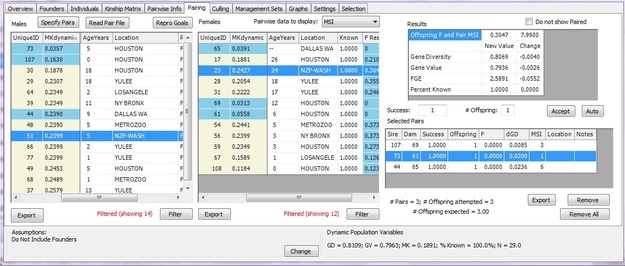

And then there are the pages that show every possible pairing within a breed, with possible positive or negative outcomes of genetic combinations.

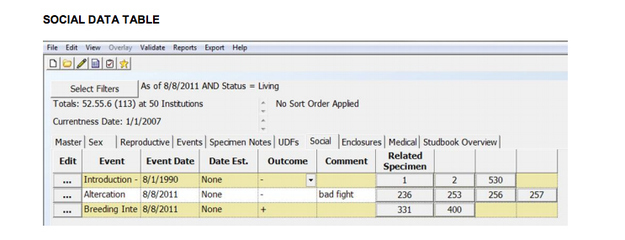

And all kinds of data can be tracked. "Sex Events" — not, as I first thought, sexual milestones like losing your virginity, but the biological sex of the animal. (It's not always fixed at birth!) But even personality trademarks are noted, like in this "Social Data Table."

For all the number-crunching that Long and her staff do, they don't simply rely on computers to determine couplings — "there's definitely an art to it." The staff considers factors like species' behavioral patterns (like their receptivity to artificial insemination, for example) and individual animals' predilections. Geography must also be taken into account: a genetically perfect pairing might not work if the two animals are across the country and one is known to only have a very small mating window.

The zoos also have a big say —they have a 30-day window to respond to PMC's breeding recommendations. The institutions, all looking to keep their bottom lines intact, may not agree, for instance, that moving one of their star animals to another zoo to be mated is possible (either temporarily or permanently).

Then there's the matter of the babies themselves. There are simply no guarantees in mating animals. A recent front-page New York Times story noted that 40 percent of managed breed populations are shrinking instead of growing. Long admitted that mistakes are made: a male bird, for instance, had been persistently miscategorized as a female leading to a series of puzzlingly unfruitful interactions. ("One institution said, 'she fights a lot!') Any number of other factors — nutrition, the weather, habitats — can inhibit breeding as well. Sometimes the animals just don't like each other. And only recently has software been created (PMCTrac) to measure the effectiveness of the PMC's recommendations.

Sometimes the stars align, though, and all the planning pays off. The Oakland Zoo had been hoping for years to host baby otters when they first built an exhibit in 2005. The PMC had recommended that Heath, a 12-year old male otter who'd been deemed genetically valuable because he was born in the wild and had no relatives in captivity, be bred long before Ginger, a 5-year old who came to Oakland from a Massachusetts zoo in 2009, was even acquired.

In the months leading up to the otter births this past February, the Oakland Zoo staff was hopeful but nervous about the pairing — "We felt pretty confident after the initial introduction between the two was successful, but until the babies are born, you are never completely sure," said Margaret Rousser, the zoo's manager, in an email. The previous year, the first time Ginger gave birth, had been hotly anticipated. Once the zoo knew she was pregnant, they set up a camera to watch her at night. And then, one morning, a staffer noticed some brown blobs. "I thought they were pinecones — she likes to play with pinecones. But then I went, 'Oh my gosh!' " Andrea Dougall told the San Francisco Chronicle. "I was speechless. Elated. I called my boss and my voice was shaking."

The pinecones turned out to be two babies, and this spring three more were born. The female is named Rose and the males are Etu and Takoda. Their breeding plans are already in the works.

A previous version of this story incorrectly called Oakland Zoo's otters "sea otters" instead of river otters and misspelled the name of Margaret Rousser, the zoo's manager.