The steady stream of polls from private firms, media organizations, and universities has become a central — and at times controversial — thread of the presidential campaign. And voters might be excused for their suspicion on a single point: What’s in it for the pollsters?

Organizations are spending between a few thousand dollars (for automated calls) and tens of thousands (for live callers) fielding state and national polls — now dropping at a rate of 20 polls per day.

They’re doing it, one way or another, for the attention, pollsters say: It’s marketing for private pollsters and universities, and it’s reportable news for media companies. But the flooded polling market does provide one potentially problematic incentive — pollsters are eager to make their surveys interesting.

“They are a marketing engine,” said Mark Blumenthal, Senior Polling Editor at The Huffington Post and the first professional pollster to get into the blogging business under the name “Mystery Pollster.” Blumenthal listed Public Policy Polling as having "created a brand for themselves by releasing their numbers publicly."

Blumenthal described PPP and Rasmussen Reports both as “small fledgling PR companies giving robo calls away into the public domain in order to promote themselves.”

PPP’s director, Tom Jensen, said the firm spends about $3,500 on each automated national poll, on top of a monthly phone bill as high as $30,000.

The Raleigh-based PPP uses exclusively automated telephone surveys to track opinion polling. The firm’s weekly tracking poll is sponsored by the giant national labor union SEIU, and distributed by the liberal blog DailyKos.

But PPP doesn’t make its money from sponsorships — their profit comes instead from the private polling, solicited by clients, that never goes public. “That’s where we make all of our money,” Jensen explained.

The pollster John Zogby said his approach is similar.

“Politics is not a major source of income, but it is a major source of branding,” he said, adding that ninety percent of his firm’s revenue is from corporate clients and international governments.

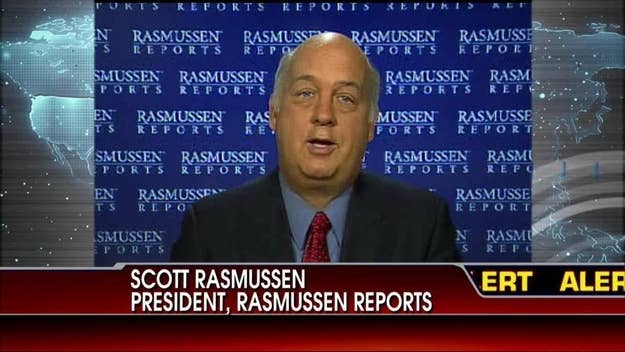

Rasmussen Reports, by contrast, operates more like a news organization. Founder Scott Rasmussen described to BuzzFeed as “a media company that makes its money by selling advertising and subscriptions.”

Rasmussen also listed the abounding ways in which his site is able to generate traffic, and ad dollars: a daily email newsletter, a nationally syndicated radio news service, an online video service, a weekly newspaper column, and a nationally syndicated TV show, “What America Thinks.”

Because of his cross-platform approach to mass-marketing, Rasmussen has become a one-man brand, appealing particularly to conservative circles, and offering his surveys as a balance to the polling conservatives believe is biased, or skewed.

Another breed of pollsters — schools like Marist and Quinnipiac who conduct well-regarded political surveys — benefit from the low cost of student callers, and from the prestige it brings to the school name.

“[Quinnipiac] credits the poll as being one of the great draws for perspective students,” said Blumenthal. “They might not learn about Quinnipiac from the football team, say, but because they’ve heard of the poll.”

Most polls that use live calling — considered reliable by analysts — are sponsored by media companies. And the big names of political polling — the television networks among them — maintain the cost is well worth the product. Tweeting about NBC News’s national poll Monday night, Chuck Todd said, “so you know, a national poll, properly done w/live callers costs anywhere from 40-60K per survey.” In a second tweet, he added, “we do it 10-12 times a year...worth it.”

Media companies get their own kind of marketing from polls — call it prestige. Despite the high costs of live calling, television networks and newspapers will hang on to their commitment to polling as an investment in news-gathering and status.

CNN, for example, often refers to its polls as “scientific,” suggesting their internals are as accurate and detailed as their reporting. When CNN partners on its widely cited polls with ORC International — a global market research firm — the cable network foots the cost of the entire poll, according to a network spokesperson. “As far as the business model,” the spokesperson said, “the polling results are made available to more than a dozen of CNN’s television networks and its digital platforms.”

But with little profit payoff for live calling, “there is a big move in the direction of robo surveys,” said Blumenthal.

And as the industry continues to shift toward fast and cheap robo calls in exchange for marketing, the categories — media, private business — may also be blurring.

“Some media companies hire reporters and assign them to cover stories. Instead of reporters, we cover the news with polls,” said Rasmussen. “We recognize that nobody we really cares about the polls, they care about the topics we poll about.”

Note: This post has been updated since publication.