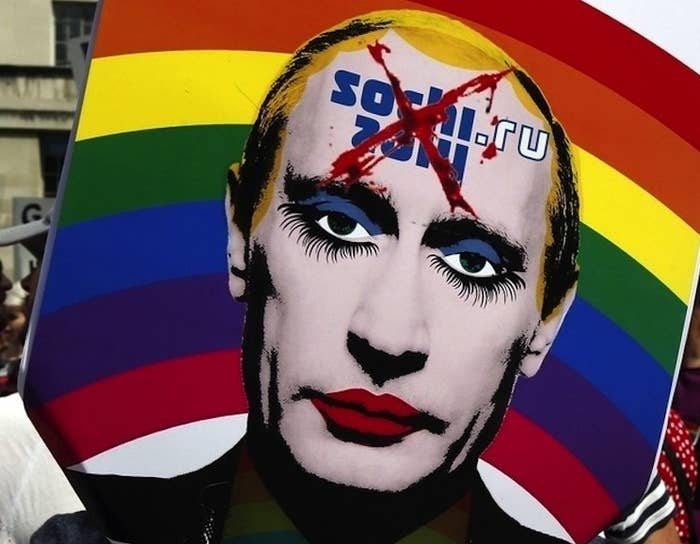

The furor over human rights at the Sochi Olympics comes at a difficult time for Russia, and specifically for LGBT rights in Russia: Vladimir Putin is positioning his country as a bulwark against decadent Western values, and it's unclear what international pressure can do about it.

That same furor, though, comes at a perfect time for the international conversation about LGBT rights. The "Gay Olympics" — as the Sochi Games might as well be known — is forcing an unexpected flood of small choices on thousands of organizations and people around the world, from the owners of Stolichnaya Vodka to the conductors of the Des Moines Symphony Orchestra.

The Olympics have always had a heavy overlay of geopolitics, and Russia's turn has come just in time to galvanize a new internationalization of the LGBT rights movement. LGBT rights have been one of the biggest stories of 2013, with the move toward marriage equality in the United States, France, the United Kingdom, and elsewhere dominating headlines — and with polls shifting favorably toward LGBT acceptance with remarkable speed. Sports, in particular, has become the new frontier as out professional athletes like Jason Collins, Brittney Griner, and Robbie Rogers; allies like Brendon Ayanbadejo, and Chris Kluwe; and the NHL and UFC have made quite clear.

And the deep homophobia seemingly intertwined with sports culture has now met another, irresistible force: publicity. There's suddenly a huge premium in attention in coming out. The NBA's Jason Collins, a solid journeyman center now in the twilight of his career, became a national figure when he came out this year. Robbie Rogers is the only player for the Los Angeles Galaxy anyone has ever heard of now that David Beckham is gone. And New Zealand's out gay short-track speedskater, Blake Skjellerup, has parlayed his identity as a possible gay Olympian into a fundraising effort to get him to the games.

Similarly, any straight athlete who stands up for her LGBT colleagues is suddenly a global phenomenon. Who would ever have heard of Swedish high jumper Emma Green-Tregaro, the bronze medalist at the 2008 International Association of Athletic Federations in the event at the 2005 IAAF World Championship but for her rainbow fingernails? She's now up to 3,000 hits on Google News. American track star Nick Symmonds has earned a strong following as well in the wake of his bold declaration in support of gay rights at the same competition.

And it's not just the athletes. With the stage set and the audience watching closely, every entity involved is forced to make a move. After broad victories in the United States and much of Western Europe over the past few years, well-organized and well-funded LGBT activists had already been looking for a new fight — and they've found in Russia a perfect contrast to an increasingly open West. Old groups like Human Rights Campaign have been through battles like this before — which the IOC's bureaucrats haven't — and they have the massive email lists and freshly tested organizing muscle to get things done. And emerging activist voices like All Out and GetEqual are using social media, well-timed protests, and sheer bravado to ensure that the outrage sparked in reaction to violent images out of Russia this summer doesn't die out before the Olympics in February.

Among the activists' soft targets are the sports bureaucracies — thousands of obscure bodies, specializing in luge or biathlon, in every country on the globe. Each has its own constituencies, its own pressure points. And each will have to make the sorts of decisions that sports bureaucrats live to avoid: What is our stance on LGBT rights? How will we deal with calls from domestic LGBT rights groups? The once well-accepted idea that sports culture functioned entirely separate from the world of politics has all but been shredded.

And fans have a choice to make too. There are levels of protest and solidarity, but the Gay Olympics will be impossible to ignore. No one in Sochi — athlete, fan or government official — will have the luxury of being a bystander.

Even Russia's police force, hardly known for its restraint, will also suddenly have LGBT and free speech issues front and center in a way that's rarely the case in the streets of Moscow. If Russia so much as lays a finger on any LGBT supporter during the Olympics, the outrage will be swift and deafening. If there is a public display of solidarity for LGBT rights in Russia (which almost certainly will happen) and Russia doesn't arrest anyone, then a powerful message will have been sent.

As for international sporting bodies, their most important choices may be about site selection. A marker has been set down, and while upcoming events are planned for deeply anti-gay regimes from Russia (in 2018) to Qatar (in 2022), those countries are now on notice that their records on LGBT rights will be affect their prospects for these prestigious events.

Less clear, sadly, is what this all means for LGBT Russians. Moscow's relationship with Washington is at a nadir, and Vladimir Putin's core political goal, to show strength, means that he is eager to stand up to human rights criticism. Many of Russia's anti-gay leaders also relish the international attention and condemnation, and the United States has yet to take the sort of concrete action — adding them, say, to the Magnitsky List of officials who are under travel and financial restrictions — that could give their actions a downside.

What will become of the "sports is a human right" platitudes and billion-watt Olympic spectacles if, after the last torch in Sochi is extinguished, the international LGBT movement is reignited while Russians are left to face their peril in the dark?