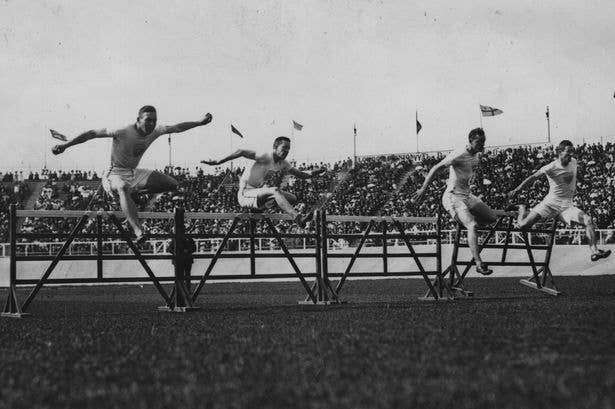

In The Beginning, There Was Cotton

When Thomas Burke won the first Olympic 100-meter dash in 1896, he was wearing a cotton t-shirt and shorts, not that different from what you'd see in a modern-day gym class. But when sprinters step the mark this week, they'll be outfitted in computer-modeled sneakers and wind-tunnel-tested polyurethane, some of the most advanced fabrics money can buy.

But let's start at the beginning.

As the 19th century drew to a close, there was good reason to use cotton. As natural fabrics go, it's hard to do better. The individual fibers of cotton have a naturally winding helix shape, which gives the resulting fabric an unusual amount of stretch. That means you can keep uniforms trim enough to be aerodynamic without restricting a hurdler's range of motion. Cotton's also very breathable, given a light enough weave. On the downside, it holds a lot of sweat, so the runners were often soaked by the end of the race.

Nylon Arrives

Nylon was first developed by DuPont in 1935, but the synthetic fabric didn't make it to the Olympics until 1948, via the first nylon bathing suits. Almost immediately, it was hard to imagine swimming without nylon. The material itself is made up of long carbon chains that don't absorb nearly as much water as a vegetable-based compound like cotton. That means there's less weight to hold a swimmer back, and a more frictionless way to move through the pool.

The Cleat

Track shoes got lighter and lighter, helped in part by a new reliance on nylon uppers (that's the "upper" half of the shoe; everything that isn't the laces or the sole), but a bigger change came in 1968 with the shift from cinder tracks to the spongy synthetic surface you see on most modern tracks. Spikes got shorter and the soft tracks allowed shoemakers to use thinner soles that made shoes even lighter.

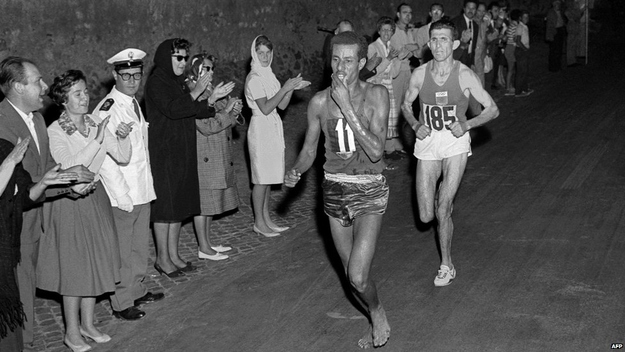

Going Barefoot

That's assuming you need shoes at all. Ethiopia's Abebe Bikila won the Olympic marathon barefoot in 1960, and barefoot partisans have been using him as a talking point ever since. Barefoot advocates are a vocal group in the running world, claiming that less cushioning encourages bad form. It's been shown that the cushioning of a running shoe can cause a runner to strike the ground harder and shift their weight more towards the heel, both of which can be problematic in a single race and in the long term. Otherwise, the science is mostly a wash. Barefoot runners still pop up in the Olympics from time to time — most recently, Kenya's Tegla Loroupe, who ran barefoot in the marathon and 10k in 2000 — but it's hard to say if it provides an advantage.

The Runner's Singlet

By the 1970s, synthetics had worked their way into running uniforms and the split between distance runners and sprinters became more pronounced. Marathoners opted for sweat-wicking singlets, designed to be as light as possible without absorbing the moisture (and weight) of sweat. Speed runners were more concerned with aerodynamics, which meant a shift to form-fitting speed suits that kept the runner's profile as slim as possible. By keeping the fabric taut, they could make sure the path of air around the body wouldn't be obstructed by wrinkles or loose flaps of fabric. Sprinters wouldn't get into more structurally advanced fabrics until recent games, but they were already thinking aerodynamically.

Nike Swift

Computer modeling opened up a whole new era in materials science, and for Olympic runners, that meant the advent of wearable fabrics so smooth they create less air friction than human skin. The Nike Swift uniforms in 2008 are a prime example, with friction-reducing sheaths on the parts of the body that move the most, like the calves and forearms. The sheaths were made from 3M's Scotchlite material, a fabric composed of thousands of powder-like beads, and more often seen in reflective strips like this. This was the first time the material had been used for aerodynamics, but tests revealed it reduced air friction by up to 55 percent. Also, it made sprinters look like extras in Tron.

The Speedo LZR

The Speedo LZR is the most effective hi-tech uniform the Olympics has seen — so effective that it led swimmers to break 130 world records in the 17 months after its Bejing debut, and was subsequently banned from the sport. There had been hydrodynamic suits before, but the LZR also compressed its wearer's upper body (creating an even more hydrodynamic shape) and added buoyancy. In areas like the upper legs in which swimmers don't need a wide range of motion, the LZR sacrificed flexibility for sheer speed by replacing the fabric with stiffer planks of polyurethane that lowered drag by 24 percent.

The Nike Flyknit

Newly emerged from a four-year development process, the U.S. team's new shoe for 2012 is Nike's Flyknit, which is woven together for a flexible, socklike feel. The shoe relies on a lightweight polyester yarn for its upper, but a lot of the technology here is in the construction rather than the materials. All the internal construction of the shoe, from the tongue to the structured fit, was accomplished using a network of knit cables of varying elasticity. The shoe is knit together rather than stitched and glued, which makes it a full 20 percent lighter than the shoes marathoners wore at the last Games — a size 9 is just 5.6 ounces. You'll see it on the feet of U.S. marathoners in this year's games, and Adidas is already supplying its athletes with a similar shoe dubbed Primeknit.

The Nike TurboSpeed

For 2012, Nike unveiled the TurboSpeed, the most advanced speed suit they've ever produced (at least until the next one). Instead of trying to make the fabric as smooth as possible, Nike added golf-ball-esque dimples to the surface of the polyester, after extensive wind-tunnel research revealed them to be more aerodynamic. They say they'll shave .023 seconds off a runner's time in the 100m dash. If true, it could easily be the difference between bronze and gold.