When Blizzard unveiled Diablo III, one of its most-hyped features was the Auction House, a free player-to-player market where characters could buy and sell items. Instead of having to kill monsters until one of them dropped the right enchanted lance, players could buy it with in-game gold or real money. The free market would make sure everyone got what they needed and no one got ripped off.

At least that was the idea.

Instead, it's been an ongoing headache since day one. The initial glut of new users created huge demand for the low-level items beginners need, which drove up those prices to astronomical levels. Gold farmers inflated the currency, driving prices even higher, and because of restrictions on how quickly users could change prices, the market was slow to respond. Within a month, the auction house was effectively broken. The only items for sale were ludicrously expensive starter gear, which funneled money to gold farmers and was useless to everyone else. Blizzard responded by gritting their teeth and instituting a set of unpopular new restrictions on users. It's an ongoing story, but one thing is already clear: they would have been better off with an economist on board.

A surprising number of companies already have one. In-game markets are an increasingly popular (and lucrative) part of the industry, especially with the rise of free-to-play games like Valve's Team Fortress 2, which rely entirely on in-game transactions to pay the bills. But if a company can't keep those markets running smoothly, their product will have a hard time breaking even.

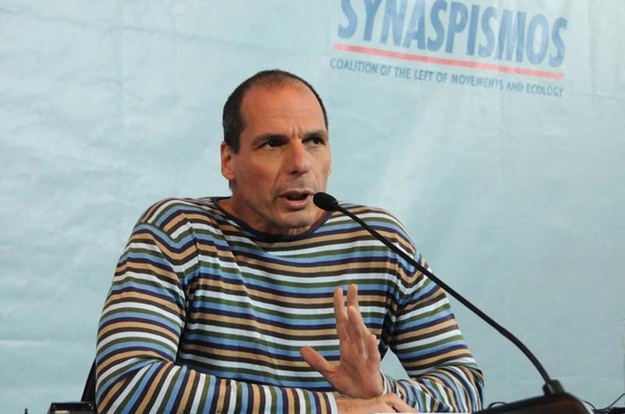

As a result, macroeconomists have never been more in demand. In the past few months, Bungie and Fiveonenine Games have both posted job listings for in-house "economy designers." Just last week, Valve brought on a Greek economics professor named Yanis Varoufakis to serve as their economist-in-residence, after Varoufakis emerged as one of the popular commentators on the Eurozone crisis. In a blog post describing why Varoufakis was hired, Valve co-founder Gabe Newell said he kept looking at payment problems in Steam and thinking, "this is Germany and Greece."

Nearly all multiplayer games rely on some kind of market to give players incentives, even if the currency is just points. But when designers layer real money markets on top of that, the results can be hard to predict. As Varoufakis told us, "once we start trading items or assets with each other, there is the possibility of arbitrage, there are bargaining instances, there's even room for futures markets. Suddenly the game itself becomes immaterial." You may be trying to level up your World of Warcraft character, but the girl next door is stockpiling entry-level armor and selling it off for cash.

That works fine for experimental markets like Second Life or the stranger corners of Bitcoin, which are content to set rules and let the markets go where they will — but most game companies can't afford to let their economies evolve organically. Lloyd Melnick of fiveonenine put it to us this way: "If your economy is broken, your game is broken."

And just like the regular economy, there are lots of ways for things to go wrong. When I spoke to Varoufakis, he was more concerned about asset bubbles than inflation. "Bubbles break, and then there are a lot of heartbroken people. And companies don't like their customers to be heartbroken." The asset might be in-game real estate or character upgrades bought with real money, devalued by an influx of users or overpriced due to a brief surge in demand. As long as there are players who feel cheated, the designers have a problem on their hands.

It's particularly challenging because gamers have so much practice exploiting these systems, even when they're just accumulating 1UPs and experience points. World of Warcraft has famously struggled with gold miners for years, and some estimate they've taken nearly 12 million gold units out of the game economy, walking the line between stat-pumping and fraud. Just last week, the space-themed MMORPG EVE Online saw a group of players game their newly implemented loyalty system for $175,000 worth of in-game currency. If there's a weak point anywhere in a game, users will find it, and every time the designers add a new asset class, a new set of markets springs up with a new set of loopholes.

Politics also plays a role. Unless you can convince users that your changes will make things better, you're likely to have a revolt on your hands. And as Varoufakis has noticed, gamers are an ornery bunch: "They don't roll over when a rule is introduced. They have full discussions in public, they challenge the logic, they say it is not right." As a result, game economists have to temper their ideal solution with gradual implementation and political maneuvering — just like the Federal Reserve.

The good news is that, unlike the Fed, these central bankers have complete data on every in-game transaction and near-total power over the supply of currency and items. They can even run experiments, something economists have struggled with since the discipline began. Varoufakis described one possible experiment that would let users pay $2 to boost the drop-rate on items for them and everyone who plays alongside them. In theory, people who pay extra should be the best-loved players in the game — but you'd never know until you tried it out. And working in a large enough ecosystem (like, say, Valve's Steam platform), it's easy to imagine a company churning out a few experimental games just to test out a payment model.

If it can stop the next Auction House debacle, it would be well worth it.