In May, the Repertorio Español on Manhattan's Upper East Side hosted a reading of Pablo García Gámez's play Oscuro, de Noche. Set in Caracas, Venezuela, the play chronicles the circumstances surrounding the death of Kenny, a young man gunned down while riding his motorcycle. I'm seated next to García's husband, Santiago Ortiz. Before the lights come down, 52-year-old García walks over from his director's box to greet us. He's in a long-sleeved black button-up shirt and jeans and wears wire-rimmed glasses, his graying light-brown hair neatly trimmed. Ortiz, 58 years old, tall, barrel-chested, and wearing a yellow collared shirt, looks longingly at García. As Ortiz watches him walk away he sighs, "Ay, mi papi."

García welcomes the audience of 100 or so people, beaming with pride. An hour or so later, the misty-eyed crowd gives a standing ovation. The performances are gripping and transport you to a fateful night, exploring complex themes of police corruption, journalistic integrity, love, family, and things that happen under the cover of darkness. In the subsequent Q&A, García tells the audience the play is based on the true story of a young man in Puerto Rico.

But that isn't exactly true. The story is based on a real young man — Kenny, García's nephew — but he lived in Venezuela, and García never met him. For the last 20 years, in fact, he's been unable to leave the United States due to his immigration status. Oscuro, de Noche, "dark, at night," has been García's reality for more than two decades. The play seems to be his attempt to recreate an experience he could not be a part of, the actors portraying emotions he can only guess at because he's been away for so long.

García and Ortiz celebrated when the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the Defense of Marriage Act on June 26. After living in the U.S. for 20 years, García did not have a green card and had no means of legal employment; and despite their legal marriage in Connecticut, the couple had lived in constant fear of Pablo being deported to his native Venezuela. Like tens of thousands of same-sex binational couples across the country, they saw the court's decision as the answer to their prayers for equality with heterosexual immigrant couples.

García didn't jump a fence to enter the U.S. He didn't come here looking for a better job or fleeing political persecution. Like many other immigrants to the U.S., gay and heterosexual alike, he fell in love and has risked family and career in order to remain in the U.S. with Ortiz, forced to choose between his love and his life. And even now, their struggle continues.

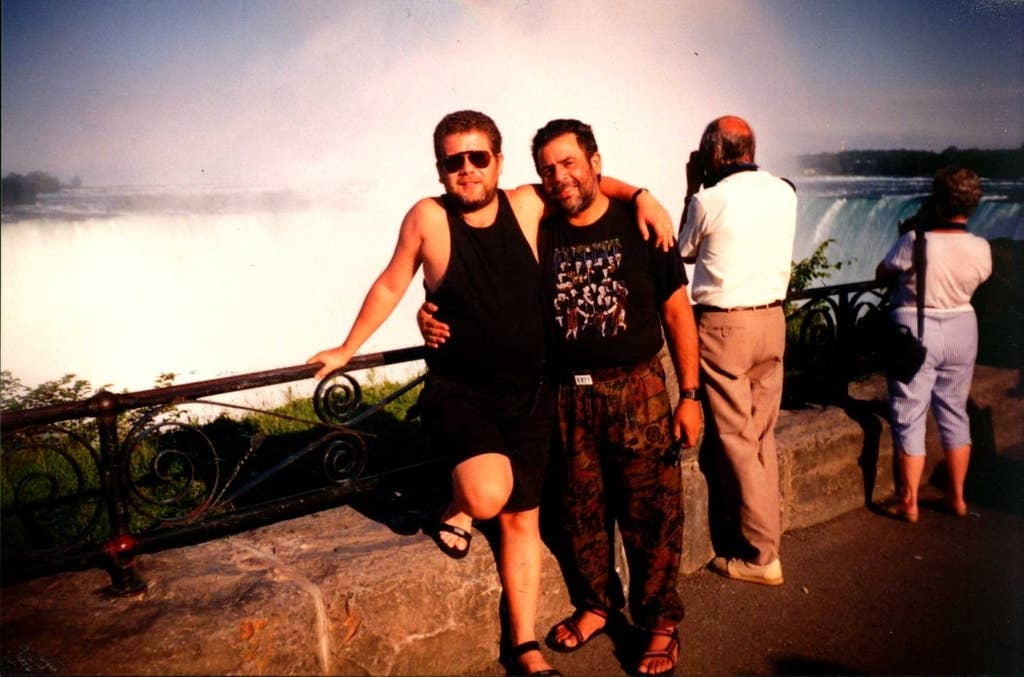

On a hot August night 22 years ago, Santiago Ortiz was living half-time in Puerto Rico with his parents and half-time in Venezuela, on medical leave from his job as a psychologist at New York City's Rikers Island prison. He went to Bar La Cotorra, one of the oldest gay bars in Caracas, to meet up with a man he had met earlier that day — who never showed. Ortiz, dressed in a yellow shirt and khaki pants, with a daring hoop earring in his left ear, spotted García.

García was a regular at La Cotorra, which was near his job at advertising firm Leo Burnett, and was chatting with a friend the night that Ortiz caught his eye from across the bar. "He was very nice looking. Mustache, big eyes, black," García says.

Ortiz bought García a Cuba Libre and showed off a business card from his New York City job as a bilingual school psychologist. García responded by opening a local newspaper to show him an art review he'd just published. Ortiz was impressed.

They spent the next day hiking in the mountains of El Ávila and talked about their lives and the homophobia they'd both experienced as gay Latinos. Soon they started dating and, despite the less-than-tolerant climate then for gays and lesbians, both introduced one another to their families, García traveling to Puerto Rico to meet Ortiz's parents. After Christmas that year, Ortiz returned to his home in Elmhurst, Queens, to resume his job at Rikers. But he couldn't stop thinking about García. Four months later, after dozens of letters and almost daily phone calls, he asked García to move to New York — and he did.

Today, they live in that same one-bedroom apartment in Queens. On the day I meet them, I'm greeted enthusiastically at the door by a snarfling pug named Benito and the smiling couple, who immediately take my coat and bag and ask if I'm hungry.

Like most New Yorkers, they make up for the lack of space with creative furniture arrangements and decorations. Their walls are alternately painted bright orange, salmon, and mango and sparsely decorated with a few framed paintings. Most of their living-room space is taken up by tall bookshelves filled with hundreds of books, one topped with a Thai Buddhist sculpture. Ortiz describes the décor as their "minimalist phase."

Ten minutes after arriving, I'm sitting in the living room with a slice of roscón de guayaba, a Colombian pastry filled with cream cheese and guava, and a steaming cup of café con leche. Benito is at my feet, anxious to see if I might give him a bite, and the two begin recounting the past two decades. After García came to New York, the couple were initially optimistic that things would work out, even though gay marriage was a pipe dream.

"This was pre-9/11, and all through my upbringing I had the idea that it wasn't that hard to become a U.S. citizen," García explains. "My father would always say, if you come to this country, if you're a decent working person, you don't get into trouble, this country is open for you."

When García arrived in 1992, he didn't speak English, but his experience in Spanish-language writing, reporting, and advertising enabled him to get work as a freelance writer, which he supplemented with catering, painting, and coat-check jobs. He decided to overstay his temporary visa in 1995. Now an accomplished playwright and Spanish teacher, García speaks heavily accented fluent English and has a master's degree and pending Ph.D. from the City University of New York (CUNY).

In the last 12 years, though, the climate has become increasingly hostile to immigrants. Having watched the number of deportations increase to record highs, García and Ortiz were anxious to find a permanent solution. For heterosexual binational couples, marriage is often the easiest way for noncitizens to remain in the U.S. legally. There are approximately 24,700 same-sex couples in the country consisting of a U.S. citizen and an undocumented immigrant, many of whom are legally married in one of 13 states where same-sex marriage is legal. But because DOMA prevented Ortiz and García from using the marriage route for a permanent immigration solution, they were forced to try other strategies.

One approach is their participation in the lawsuit Blesch v. Holder, one of more than a dozen immigration-related cases that aimed to prove DOMA unconstitutional. The advocacy group Immigration Equality filed the lawsuit on April 2, 2012, on behalf of five lesbian and gay couples with immigrant partners from countries including Japan, South Africa, Spain, Venezuela, and the United Kingdom. Their co-plaintiffs have each suffered greatly. Frances Herbert and Takako Ueda met in Michigan as college students, for example, and, because of immigration issues and societal pressure, were separated for 16 years before being reunited and legally married in the United States. Kelli Ryan and Lucy Truman met in medical school in Scotland and were married in 2010, but Truman has had to remain in the U.K.

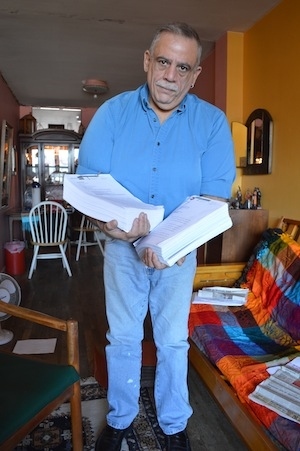

Ortiz brings out three expandable brown file folders. From them he withdraws several bound stacks of white paper and puts them on the couch next to him.

"This is our lawsuit," he says, almost tenderly.

While he sifts through thousands of pages of legal documents, García sits at his computer, browsing photographs from their simple wedding in Connecticut two years ago. In the photos, he wears a bright red long-sleeved cotton shirt, Ortiz is in a nearly identical orange cotton sweater, and both wear khakis. They were married by a justice of the peace on a sunny day.

"It was just the two of us," Ortiz says.

That Connecticut wedding seemed impossible to Ortiz 20 years ago, in part because he didn't believe he'd still be alive.

Four years before meeting García, in 1987, Ortiz was diagnosed as HIV positive. He'd planned his trip to Venezuela, in fact, after a friend in Puerto Rico suggested he explore alternative, holistic medicine there. At the time, HIV/AIDS treatments were still in the early stages of development, and Ortiz was scared. "All my friends were dying," he says.

He waited for three months after they met to tell García he was HIV positive, and eventually decided to do so in a letter (he was still in Puerto Rico). García's response didn't arrive for several weeks, and Ortiz was convinced he had been dumped. But García responded favorably, saying he still cared for him, and wanted to continue their relationship.

"I think the best medicine I found in Venezuela was Pablo. Because he made me feel happy, he made me forget about AIDS," he says.

Being the partner of a person living with AIDS has not been easy for García. He remains HIV negative, taking precautions and treatments like many other serodiscordant couples do. He says he was shocked when he first arrived in the U.S. and learned about the challenges he would face at a meeting at the Hispanic AIDS Forum. Alerted to the risk to his own health and the possibility of watching his partner die, he went home and downed a bottle of rum.

But throughout, he's been a daily support for Ortiz, vigilant to the ebbs and flows of treatments, responding accordingly as medications make him weak or lose his appetite. Seven years ago Ortiz was diagnosed with cancer, and García remained at his side as he underwent chemotherapy and radiation treatments. They've also both struggled with depression, overwhelmed by the all they've faced together and the uncertainty of what lies ahead for García.

Though they would have never met if not for Ortiz's diagnosis, fear of separation has been intensified by his looming mortality. Had anything happened to him, García would have had to leave immediately with no legal rights to the life they've built together. And, most importantly, Ortiz would have lost his primary caregiver were García deported.

In addition to participating in Blesch v. Holder, García had applied for deferred action, a program introduced last year by the Obama administration that offers temporary protection from deportation. Deferred action, which is called a "band-aid" approach by immigrant advocates from the New York State Youth Leadership Council, is typically limited to undocumented youth who arrived in the U.S. before age 16. But sometimes the Department of Homeland Security will extend deferred action to immigrants like García who are "vulnerable to separation," according to Steve Ralls at Immigration Equality. U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) granted Pablo two years of deferred action on March 21, and since then he has applied for and received a work permit and temporary Social Security number. It is very likely his green card application will be reviewed and accepted — and yet they'll believe it when they see it.

Despite these decades of unbelievable stress, the times I've met the couple, they are mostly upbeat, supportive, and loving. Ortiz refuses to dwell on his health problems, saying how fortunate he feels to be alive. And García is entirely focused on his career. Just a week after receiving his work permit, possible now because of his deferred action, he secured positions teaching Spanish at Brooklyn College and the City College of New York, which he began in August.

In their living room, they tell me what they love most about one another.

"My favorite thing about Pablo is that he loves me. That's it, that he cares about me — and I never thought anyone would love me. Period," Ortiz says, tearfully.

"His smell," García says in a thick accent, each syllable deliberate and staccato. He looks down bashfully. "How his skin smells. It's like a kind of perfume that makes me feel sure."

Of everything they've been through, perhaps the most difficult part has been García's protracted separation from his family. As Ortiz flips through the pages of their lawsuit, he stops at a copied photograph of his late mother Esther with Pablo's mother Graciela, which was taken on a family vacation to Puerto Rico before García was barred from leaving the U.S.

Trying to maintain García's connection with his family, Ortiz traveled to Caracas twice on his partner's behalf. He would stay at a hotel and visit with Ortiz's mother and father, as well as with his three younger sisters and close friends. But he stopped visiting because it became painfully clear that the person they all really wanted to see was García.

After the DOMA ruling, García and Ortiz attended a barbecue hosted by another couple who previously faced imminent deportation, and they marched in the annual NYC Pride Parade. But on that very day, they received news that brought their celebration to a halt, and further highlighted the insecurity of their situation.

In December, García's mother in Venezuela began having serious health problems. She was diagnosed with "dropped head syndrome," a rare neuromuscular condition that disabled her and caused extreme pain.

That Pride Sunday, García learned from his sister in Venezuela that their mother had taken a turn for the worse, and he decided that despite fighting for the last 20 years to remain in the U.S., he would return to Venezuela knowing he would be denied reentry and be separated from his husband. Immigrants who remain in the U.S. without proper authorization for more than 180 days are subject to a three- to 10-year bar from reentering the country, and because his temporary visa expired 18 years ago, he would likely receive the maximum. He was determined to leave nonetheless.

The Supreme Court's historic decision to repeal DOMA went into effect immediately, leading same-sex binational couples across the country to begin applying for green cards. Because García and Ortiz had previously applied, paying $1,490 for an application that was ultimately denied, they decided to wait for their petition to be reconsidered instead of refiling. At least another 70 couples in the U.S. are in a similar holding pattern, waiting for prior applications to be reviewed. The Department of Homeland Security has not yet issued a clear timeline for reprocessing applications submitted by same-sex couples.

In the end García did not have to leave; his mother, Graciela García Gámez, died before he could. He could not secure the emergency travel authorization needed in time to go visit her before she died. He also missed her funeral, which was held at El Cementerio del Este in Caracas, just as he had missed his father's funeral 16 years ago.

The day after, Ortiz explains why things happened this way, demonstrating how their battle for equality has consumed their lives: "We think she understated her condition so Pablo did not do something rash. She did not want to interfere with his immigration struggle."

This story comes to us from Feet in 2 Worlds, a project of the Center for New York City Affairs at The New School that brings the work of immigrant journalists to public radio and the web.