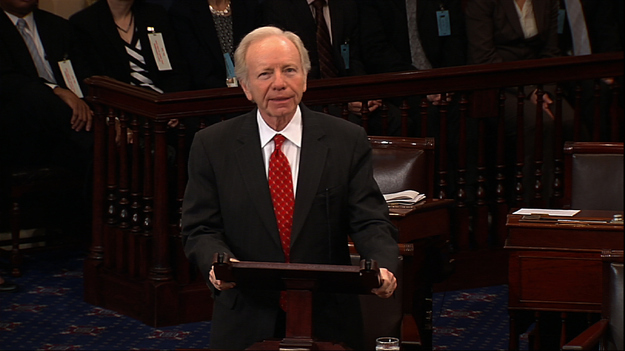

Joe Lieberman has served in the Senate for 8,765 days, and his final one will come Thursday when the 113th Congress convenes at noon. He entered it a star of a new Democratic Party that emerged transformed by the Reagan generation. He leaves it isolated and marginalized, more a curiosity than a powerhouse. The Democratic nominee for Vice President in 2000, he’s now a man without a political party at all.

Lieberman’s arc is the mirror of a whole strain of Democratic politics, one that was born, as much as anywhere else, on the Yale University campus in the early 1960s, and one that reached its peak when a young volunteer on Lieberman’s first State Senate campaign, Bill Clinton, was elected president. These New Democrats shared many of the liberal values of the more radical campus voices of their time, but their sympathies were clearly with the elite. Many, like Lieberman, were the heirs to the unabashedly elitist liberals of the 1950s and 1960s, people like Lieberman’s mentor, Yale president Kingman Brewster, Jr.

I was, more by happenstance than anything else, an intern for Lieberman for three and a half weeks in the summer of 2008. The Senator had just survived a bitter primary challege, keeping his seat at the cost of his place in the Democratic Party, and I found the contradictions in his legacy fascinating then. Later, I spent six months in the restricted archives at Sterling Memorial Library on Yale’s campus as part of my research for my senior thesis on the retiring senator, reading dozens of Lieberman’s editorials in the Yale Daily News and volumes of private letters.

What I found there was a surprising clarity in the clear line between Lieberman’s stellar early career and his ultimate fall from Democratic Party graces. What I found also contradicts the Democratic conventional wisdom, that Lieberman transformed himself after he and Al Gore lost the 2000 election. Indeed, from his days on Yale’s campus in New Haven, Lieberman has been remarkably consistent to the socially liberal, foreign policy hawkish ideology he demonstrated as a student.

In school, Lieberman hitched his wagon to a dying ideal — that rich, well-educated, WASPs with the noblest of intentions were gathering to further a more perfect country as they saw it. Nearly all saw Vietnam as a necessity at the start, and slowly came to reckon with that error as they got caught up in it and were marginalized by the Woodstock generation. Lieberman, in some ways the zealous convert to that old ideal, never lost track of it. But he was also influenced by deeply conservative and liberal mentors, who shaped his thinking, but who could never win him over completely to their causes.

Lieberman’s ideas and his impulses always took him a few degrees to the right of his party, and as the center of gravity shifted to the left — first over the Iraq war, and then fully in the rise of Barack Obama — he found himself losing his footing. The moderates in both parties became relics, and this time, Lieberman couldn’t adapt.

Joe Lieberman was drawn to everything about Yale University that was just beginning, in the early 1960s, to feel out of date. He was the son of a Stamford liquor store owner, attended the only public high school in a city dominated by tony private institutions, and earned admission to Yale as his senior class president, making him the first in his family to attend college.

When Lieberman entered Yale as a freshman in 1960, he quickly joined the Yale Daily News — the oldest college daily newspaper, with a tradition of breeding leaders like Henry Luce, Sargent Shriver and William F. Buckley, Jr. As one of the few reporters from Connecticut, he gravitated to covering state politics in his first year, before focusing on University administration.

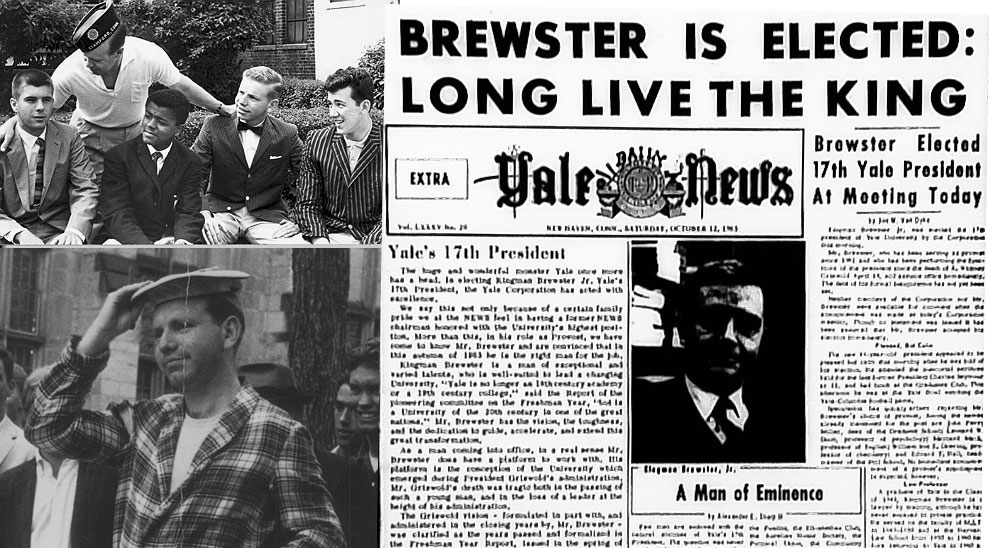

Among the large figures on and around campus, the one who would become Lieberman’s mentor and his model was Kingman Brewster Jr., who also arrived in 1960, as the new provost. A Yale alumnus and Harvard law professor known for his progressive ideals and conservative temperament, Brewster was brought in by President A. Whitney Griswold to modernize the school’s academic culture — and he would go on to revolutionize the very character of the school. After Griswold’s death in April 1963, Lieberman was Brewster’s biggest cheerleader in his bid to assume the Yale presidency on a permanent basis. “Brewster Is Elected: Long Live the King,” read a banner headline above the nearly century-old paper’s nameplate. Lieberman used his perch as the chairman of the News — then, and now, the most influential student post on campus — to help fulfill Brewster’s vision for the school, advocating for everything from coeducation to curricular reform.

But Lieberman’s activism came in the most staid and traditional form available. Henry “Sam” Chauncey, Brewster’s chief of staff and later Yale’s Secretary, described Lieberman as among the most straight-laced undergraduates he remembers.

“If you take his politics in the ‘60s and ‘70s he would have been seen as a very liberal person on racial issues,” Chauncey told me in an interview at the storied Yale haunt Mory’s. “But at the same time he was this very conservative student — always wearing a coat and tie. It stands out because we were entering the era where students were calling you one four letter word after another.”

Lieberman’s relationship with Brewster nearly collapsed after Brewster all-but-ordered the Yale Political Union to disinvite the unabashedly racist Alabama Governor George Wallace over fears of protests. Lieberman vigorously defended the invitation in the Yale Daily News on the grounds of freedom of speech, saying fears of rioting in response to Wallace’s visit expected the worst of peaceful civil rights protestors. In a letter to Buckley he wrote that the break with Brewster caused him “some personal doubt.” But at the same time Lieberman defended Brewster from the personal attacks of undergraduates and faculty members critical of Brewster’s decision. (They called the university president a stooge of New Haven Mayor Richard “Dick” Lee, who was worried any protests would harm his reelection chances, a charge Lieberman rejected in an editorial as baseless, despite evidence to the contrary.)

“Here is Joe, who might have had a rebellious thought, but he would never express it in a rebellious way,” Chauncey said. “Joe disagreed with Brewster, but still thought the world of him.”

Brewster, himself a former chairman of the News, took Lieberman under his wing — frequently calling on him to attend meetings with members of President John F. Kennedy’s inner circle like Dean Acheson and McGeorge Bundy. “We need you! Please call me at my earliest convenience — which is now,” Brewster sent in a letter to Lieberman to summon him for advice on one university decision. At Brewster’s request, Lieberman led a parallel review of the ultimately nixed proposal to merge Yale with Vassar. When President Lyndon B. Johnson placed Brewster on the National Advisory Commission on Selective Service in 1966, he took Lieberman — then a Yale Law School student — along to provide testimony and conduct research. Lieberman and Brewster were both critical of student deferments as inequitable — not an obvious stance to be taken by a University President and student who avoided the draft on one through college and law school.

Brewster’s biographer, historian Geoffrey Kabaservice, examined his subject in the pantheon of the dominant “liberal establishment.” Bundy, New York Mayor John Lindsay, Nixon Attorney General Elliot Richardson, and Carter Secretary of State Cyrus Vance, were all close friends of Brewster’s and leaders of the age. In many respects, Brewster and his friends were the status quo against which the counterculture “radicals” rebelled — the moderate Republicans and Democrats who thought liberally but lived conservatively; supported the civil rights movement but were supportive of the Vietnam War. But to Lieberman they were the ideal.

“Probably more than anyone at Yale, Brewster influenced me the most,” Lieberman recalled a few months after announcing his retirement in an interview he gave me in the spring of 2011 at his cousin’s law offices in Stamford. “He was extremely honorable. He was a man of the law and took it seriously. He represented to me the best of Yale, the best of an older America — a kind of, if you will, White Anglo Saxon Protestant America.”

Working for Connecticut Democratic boss John Bailey, the Democratic National Committee Chairman at the 1964 National Convention, Lieberman wrote to Brewster that he was “bemoaning your association with the Republican party. Otherwise you would certainly figure in Vice-Presidential speculation.” (Lieberman’s senior thesis at Yale was a biography of Bailey entitled “The Power Broker” that endeared him with the boss and his supporters for years to come.) Lieberman represented the Democratic establishment at that convention, one that was already fracturing between party-loyal activists, and the more radical and liberal groups that would become a major force in the party later in the decade.

Brewster’s final charge to the Class of 1964 was simple — as the world changes, embrace it, but do not lose track of what is right. Speaking at the formal baccalaureate service before the grand organ in Woolsey Hall, which adjoined the campus’ memorial to alumni dead in war Brewster declared, “A danger posed by the advance of the understanding of human behavior is that it tempts a moral timidity… Conscience, too, becomes calloused over in the name of realism. In their private relationships people are treated as objects to be used and then discarded. In public life all is excused by a “what do you expect” of the Bobby Bakers, whatever the depth of the corruption, whatever the height it reaches. Moral neutrality, calling itself sophisticated, admires the perfect politician’s politician as it would admire the perfect crime.”

It was a message Lieberman never forgot.

If Brewster represented the ideal of an old liberal America, the other towering figure of Lieberman’s time at Yale was the icon of conservative reaction: William F. Buckley, Jr.. Buckley was by then the founder and editor of National Review but, until his death in 2008, he maintained a tradition of keeping tab on News editors. His eyes at the paper included the longtime business manager of the Yale Daily News, Francis Donahue, who described the young Lieberman to Buckley in a letter dated Jan. 3, 1963 as “a Democrat of the first water but he is honest. The guy is okay.”

It was high praise from a man who had been involved with the publication for decades and would describe the Board of 1970 to Buckley in tumultuous April 1969 as ““#$%_&’()*.” Buckley would prove to be an important influence for Lieberman, and the pair would go on to trade letters for the rest of Buckley’s life.

Lieberman shared Buckley's strident anti-Communist views, and the pair generally agreed on foreign policy issues. “In a Young Democratic election at the Yale Law School I was compared to the late Senator McCarthy and thereafter was bitterly attacked by [Yale] Chaplain [William Sloane] Coffin for the “loftiness” of my statements in support of the American commitment in Vietnam — both of which, I trust, will delight you,” Lieberman wrote to Buckley in 1965.

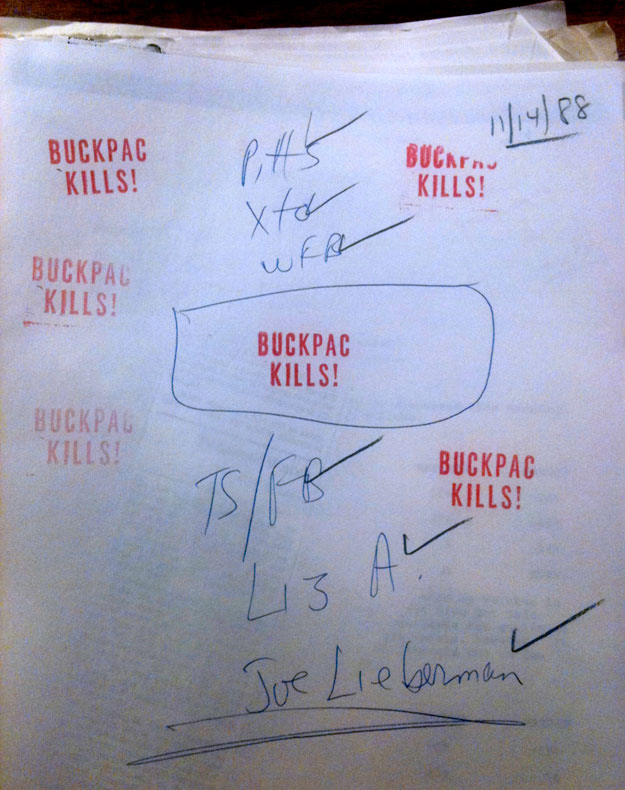

Their friendship, cemented over many dinners at Buckley’s home in Wallack's Point, proved invaluable in 1988 to Lieberman, when the National Review founder created “BuckPac” to “Relieve Connecticut of Lowell Weicker & Other Good Things.” Lieberman, then Connecticut Attorney General, was challenging the incumbent Republican to represent the state in the Senate. Buckley appears to have had President Ronald Reagan’s tacit approval, sending him a preview of his National Review column announcing the PAC “for your private delight.”

“I promise not to tell anybody I have shown it to you,” Buckley wrote in a letter dated three months before the column’s publication. “But I could not withhold the sheer pleasure of it from you and Nancy.”

In a letter outlining his campaign agenda to Buckley in 1988, Lieberman played to Buckley’s foreign policy agenda, saying that he would “ask Weicker to explain whether there is anywhere in this imperfect world of ours where he would support the use of American military force to protect our national interests and national principles since he has criticized the bombing of Libya, the Grenada invasion, and the Persian Gulf involvement — all of which I support.”

Buckley’s wife Patricia drove around Stamford with a “DOES LOWELL WEICKER MAKE YOU SICK?” bumper sticker, as the PAC raised a bit of money, but mostly awareness through pages in Buckley’s magazine and local and national news reports. Buckley told Lieberman that his wife was frequently stopped asking where to buy one of the stickers. “Forsooth, I do believe I have started a prairie fire,” he wrote gleefully.

“Well now, that was a fine campaign. I wish you every success, and your program (most of it), resounding failure. It would be fine to see you one of these days,” Buckley wrote to Lieberman days after his victory, signing the letter, “BUCKPAC KILLS.”

Brewster and Buckley framed Lieberman’s life at Yale. But there were also more contemporary influences on him, led by a man of the New Left, Yale Chaplain William Sloane Coffin, Jr.

And in his first editorials in the Yale Daily News, Lieberman crafted the ideological platform on which he built his career. The socially progressive, fiscally moderate and liberal-internationalist positions he held decades later were formulated two or three times a week on Page 2. “These are our aims—to report accurately, to represent convincingly, and to lead forcefully,” Lieberman wrote in his inaugural column, launching a scathing attack on the injustices of poverty and segregation in a series titled “The American Dream.”

“It is undeniable that the American Revolution based upon this dream is unfinished business,” Lieberman said in the first of the editorials. “For at least two large groups in our society to-day—the poor and the Negro—the American dream is bunkum.”

Coffin, a former CIA officer, was an early opponent of the Vietnam War, promoting civil disobedience efforts and encouraging draft dodging, became another mentor to Lieberman on domestics issues, and encouraged him to use the paper to encourage students to face the them head on. He and Allard Lowenstein, the civil rights organizer and politician, suggested Lieberman lead a delegation to Mississippi to help the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee campaign for Aaron Henry, a prominent civil rights activist. He explained his decision in emphatic and moralistic terms in a first-person editorial titled “Why I Go to Mississippi.”

A student a year behind Lieberman, David Milch, now a screenwriter and television producer, wrote a poem that ran next to the editorial, raising doubts about the endeavor. “So you’re gonna help the poor nigger — well here’s news, white boy, this nigger don’t want your white man’s help,” Milch wrote. “No matter how hard you try, white boy, you never gonna turn out black.”

But Lieberman later described the brief trip as one of the most significant experiences of his early life. “I saw real evil,” he said in a 1992 interview about his time in Mississippi. “I saw the ability of the courage of people to use the political system in this country in a way that can’t be imagined today. And it just showed me the importance of not being too cautious — that when a moment of opportunity comes to make a difference, you should take it.”

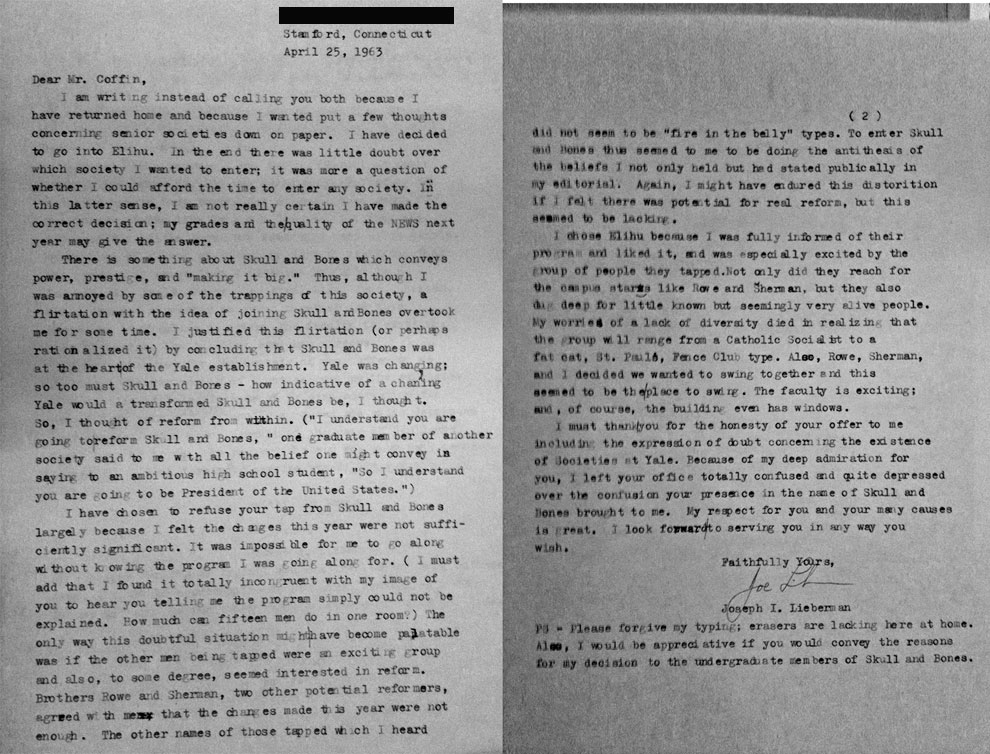

Coffin would later offer Lieberman a tap to the Skull and Bones senior society, whose alumni include President George H.W. Bush, Bundy, and Coffin himself. But Lieberman, like Brewster two decades before, would turn down Skull and Bones over concerns it was not diverse enough, writing a typo-laden letter to the chaplain.

“There is something about Skull and Bones which conveys power, prestige, and ‘making it big.’ Thus, although I was annoyed by some of the trappings of this society, a flirtation with the idea of joining Skull and Bones overtook me for some time,” Lieberman explained, saying he briefly thought he could change the organization from within. (Decades later, Buckley later became the most ardent opponent to allowing women into the group in the early 1990s, filing a lawsuit to prevent the group from admitting women. Lieberman and Buckley rarely discussed social issues, mostly because they disagreed on them. Lieberman joked of Buckley’s “subversive” agenda, and their friendship despite differences would prove to be a model for Lieberman’s work in the Senate.)

“I saw my role on the campus at that point, to be a kind of progressive voice,” Lieberman said later. “So maybe I saw the campus as more of a domestic policy than a foreign policy.”

He chose Elihu, a less prestigious society, because he was excited by its intellectual diversity, he told Coffin. “My worries of a lack of diversity died in realizing that the group will range from a Catholic Socialist to a fat cat, St. Paul’s, Fence Club type.”

Lieberman had waged a public war on the societies for their secrecy, criticizing Skull and Bones and Scroll and Key for not having windows into their stone tombs, as he had on fraternities for allegedly discriminating against black students.

Also at Coffin’s urging, Lieberman used the force of his paper to speak out against the rise of Communism and advocate for global respect for human rights. Deeply skeptical of the nuclear deterrent, which he called a “vicious and tragic circle,” diplomacy and institutions like the United Nations were central to Lieberman’s vision for America’s role in the world.

“We wish to help in building stable and free governments throughout the world—governments of law which recognize the unalienable rights of the individual,” Lieberman said, channeling the inaugural address of one of his greatest heroes, President John F. Kennedy. “We have no aims of territorial expansion. We are interested in giving men everywhere access to the benefits of modern times so that they may be removed from the chains of poverty, sickness, and ignorance.”

By 1972, when Lieberman was mounting his first campaign, the Democratic Party had been shoved to the left by the Vietnam War, and for once Lieberman moved with it, running as an anti-war candidate against Democratic State Senate Majority Leader Ed Marcus, an advocate for scaled disengagement.

Lieberman’s involvement in the Vietnam issue went back to 1965, when he and John Kerry organized a demonstration against the use of civil disobedience as a form of protest against the war. Titled “Who Speaks for Yale,” Lieberman said the purpose of the rally was “to show that those students that have yelled the loudest are not the most numerous.”

“I myself have yet to be convinced of any practical value to the raucous minority protests have had other than to elevate the morale of Communist forces in Asia to fight in the name of their totalitarian form of government,” he said.

Earlier that year, at a Young Democrats election at the Law School, Lieberman was publicly compared to the redbaiting Senator Joseph McCarthy, and Coffin's “loftiness” attack stung. “’You know you’re just acting like another Connecticut political hack,’” Lieberman recalls Coffin saying. “That really hurt a lot.”

Lieberman recalls he began to question the wisdom of America’s involvement in Vietnam after President Lyndon Johnson increased the number of U.S. troops to little effect. “He just doubled down and tripled down,” he said. “And then at some point it just seemed to me that it just wasn’t working, that it wasn’t worth it.” This would be a sharp contrast to Lieberman’s later steadfast support for the Iraq War.

“I found myself hard to pull myself away from it, because I thought there was a principle to it,” he said later, adding he considered it a fight to continue Kennedy’s vision years after his death. “It was a difficult transition for me, and I began to turn around.”

Lieberman kept his anti-war activism notably low profile. There is, in fact, no record at all of Lieberman's having attended anti-war rallies or protests or otherwise vocalized his new position on the war, but he did campaign for Robert Kennedy during his tragic Presidential bid in 1968. By 1970 Lieberman was an official in the liberal group Caucus of Connecticut Democrats, chaired by the anti-war Rev. Joe Duffey, who was seeking the Democratic nomination to the Senate.

And in a move of political cunning, even without speaking out against the war, when Lieberman ran for State Senate in 1972, he did so with the backing of New Haven’s anti-war radicals.

Lieberman’s plans for a career in public service were obvious to all around him growing up. At his Bar Mitzvah, his teacher called him a “future Senator” and continued addressing him that way, and his classmates at Yale called him “Senator” even before he graduated college. After graduating from Yale Law School in 1967, Lieberman took a job with the prominent New Haven firm Wiggin and Dana — then and now, Yale’s lawyers — partly in an effort to remain close to Brewster.

It was the combination of Brewster and the Bailey machine that propelled Lieberman into politics. In 1969, Ed Marcus from New Haven announced he would run for the U.S. Senate seat against incumbent Senator Thomas J. Dodd. Lieberman announced he would compete for Marcus’s seat and stayed in the race even after Marcus decided to reenter it after losing the Senate primary. Marcus was no friend of Bailey’s, having taken steps to assert legislative independence from the Executive Branch (which was largely controlled by the Bailey machine), including the adoption of an annual (as opposed to biennial) legislative session, part of a legislative reorganization in 1969.

“He was young, and ran an extremely aggressive campaign,” remembered Marcus, who went on to become the State Party Chair in the 1990s and now considers Lieberman a friend, “and he had a lot of help from Yale and John Bailey.”

Lieberman launched his campaign saying he would “reject the tired political rhetoric and stale political labels,” and picked Chauncey to organize his campaign. They recruited talented Yale students like Bill Clinton, then a student at the law school, to go door-to-door for Lieberman. Additionally, Lieberman received at least the tacit endorsement of Brewster, who himself was no fan of Marcus. The majority leader had helped to defeat Yale’s plan to build two new residential colleges in downtown New Haven, and was critical of Brewster’s handling of the Black Panther riots.

Lieberman’s campaign tried to portray the majority leader as disconnected from his constituents, Chauncey said, in contrast to Lieberman, who would be out knocking on doors every day. “Marcus had to spend a lot of time trying to get the Senate seat, and voters thought was not paying attention to them in the district,” he recalled, adding Vietnam was also a major issue for Marcus. “That’s why we won — it was 50% our effort and 50% Marcus’ reputation.” Lieberman defeated Marcus in the primary by four percent — 240 votes — and coasted to a smooth victory in November.

Lieberman will retire Thursday an isolated, even confusing, figure. In a country marked by ever-clearer partisan and ideological divides, Lieberman never quite chose a side among three mentors who represented utterly different, warring strains of American politics — Brewster the patrician liberal, Buckley the reactionary conservative, and Coffin the radical. And yet each was deeply important to developing the socially progressive, hawkish foreign policy positions that he burnished in Congress decades later.

Brewster, to Lieberman, represented the middle of the road strategy he would try to live by in Congress — a friend to all, guided by his high-minded conscience. Buckley was the Republican sometimes-ally with whom he shared his foreign policy views. Coffin lived out his life on the fringes of Democratic politics, and was the progenitor of the force that beat Lieberman in the 2006 Democratic primary.

And where Lieberman maintained close ties to Buckley and Brewster, he and Coffin were permanently divided. In a 2003 interview, three years before he died, Coffin told the New Haven Register “any Democrat, except Joe Lieberman, would be a vast improvement over George Bush.” And when Lieberman heard Coffin was ill in 2004, he recalls his old mentor “gave me hell” over his support for the Iraq War.

Indeed, that 1972 race was in many respects the exception that proves the consistency in Lieberman’s record — the most visible time he adopted positions necessary to win election at a time when the radicals dominated Yale and Democratic politics.

“He was about as liberal as you came at that point,” Marcus recalled in an April 2011 interview. “He was for getting out of Vietnam right away — I think that was immaturity more than anything.”

And it seems Lieberman views it that way as well, still grappling with his conversion.

“I don’t know if you found any evidence of me speaking out against the war,” he asked me, almost sheepishly, after recounting his evolving thinking on Vietnam.

Lieberman never believed he was of the anti-war movement, and felt naturally drawn to the counter-revolution “Third Way” strategy advocated by Bill Clinton and the Democratic Leadership Council. And where Clinton was a far more skilled politician, able to pacify the liberal base, Lieberman was always a frequent target for their scorn.

The Democratic Party of Scoop Jackson and even Bill Clinton had a place for Democrats who sympathized with William F. Buckley. But the modern Democratic Party — the one that brought up Barack Obama — is heir much more fully to William Sloane Coffin. It’s a tradition Lieberman never much understood, but has now rose to dominance such that it’s unlikely there will be another Joe Lieberman any time soon.