In late 2014, an obscure Russian group called a press conference in London to announce the launch of the “world’s largest international study” — a three-year, $25 million experiment of genetically modified organisms, or GMOs.

In the Factor GMO project, the panelists explained, thousands of rats would eat genetically modified corn that had been grown with Roundup, a controversial weed killer. Scientists would then watch the animals for three years, round the clock, to see if they developed cancer or fertility problems.

“We hope this will be the definitive study that will establish whether or not these chemicals and these GMO products are safe and effective,” Bruce Blumberg, a scientist at the University of California, Irvine, a longtime GMO critic and one of the three scientists originally on the project’s advisory board, told the crowd of reporters.

The event attracted wide news coverage in the British press, everyone from the Guardian to the Daily Mail. Then Blumberg flew home to California. And that’s the last he ever heard from the Russians.

"It is weird," Blumberg told BuzzFeed News.

Now more than three years later, the Moscow-based Factor GMO is not answering emails from the press. Although the donation button is still active on its website, the effort hasn’t uttered a peep since 2015. So, how much money did it raise? Did scientists ever watch any rats?

Or was it all a ruse from the get-go, a grand Russian propaganda effort against GMOs and Western science?

"Factor GMO has many of the hallmark characteristics of Russian anti-GMO propaganda, though it gives itself a veneer of scientific objectivity," Iowa State sociologist Shawn Dorius told BuzzFeed News.

Russia, as it turns out, has pushed a lot of anti-GMO propaganda in this decade, the most recent a Russia Today documentary, The Peril on Your Plate. That’s partly because of the competition: Cheap GMO crops from the US could threaten Russia’s agricultural market, and particularly its recent boom in wheat exports.

But these messages serve another purpose, too: to sow distrust in Western innovations, whether agricultural science, fracking, or elections, said Nina Jankowicz, a scholar of Russian disinformation tactics. “The basic idea is to create doubts in people’s minds, whether about Big Agriculture, or chemtrails, or anything else.”

The agricultural behemoth Monsanto began selling Roundup in 1974. Unlike other herbicides, it killed just about any kind of weed and was a runaway seller. By the mid-1990s, the company had genetically engineered crops to resist Roundup, meaning that farmers could spray it with abandon. Its use grew fifteenfold.

In the two decades since, a subindustry of scientific studies has investigated the safety of these genetically modified crops and Roundup’s main ingredient, a chemical called glyphosate.

The most notorious of this oeuvre was a 2012 report by the French scientist Gilles-Éric Séralini finding tumors in rats fed GM corn and exposed to glyphosate. The study was widely criticized for its media rollout — journalists were asked to sign strange confidentiality agreements — and its conclusions, which the European Food Safety Commision found “inadequately designed, analyzed, and reported.” The study was retracted in January 2014 and then republished in a separate journal, without any more review, in June 2014. It’s been argued over ever since, with much of the criticism focused on its small sample size of 600 animals.

Factor GMO was designed to scale up the effort, tracking 6,000 rats for three years and measuring any fertility or hormonal changes. The project’s press conference on Nov. 11, 2014, was organized by the Russian nongovernmental organization National Association for Genetic Safety (NAGS), which has a history of hostility to GMOs. The group had organized “flash mob” events for a 2014 “March Against Monsanto” in Moscow, for example.

The London meeting began with two presentations in Russian, one by the head of NAGS, Elena Sharoykina, who had already called for a 10-year global ban of these products, and the next by Oxana Sinitsyn, an environmental health scientist at the Russian Ministry of Health. (Neither responded to a request for comment, nor did the listed contacts for the study.)

“The study will take place at undisclosed locations in Russia and Western Europe.”

Blumberg, the UC Irvine scientist, opened the English language portion of the event. An expert in chemicals that disrupt hormones, he said he was joining Factor GMO’s advisory board because he was “frustrated” by past safety studies failing to answer questions about how glyphosate exposure might alter the germline, affecting children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, or even great-great-grandchildren. “This is very important to know whether these chemicals and these genetically modified organisms can have effects that are seen in those generations,” he said.

The presenters did not say exactly which scientists would conduct the study, or where it would be conducted. “The study will take place at undisclosed locations in Russia and Western Europe,” the Factor GMO website explains. “The exact locations of the study must be kept secret for security reasons as we want to avoid any outside interference.”

“That’s a great touch if you’re writing a script for a thriller, but not so great if you want to build a broad base of credibility and trust,” Nathanael Johnson of Grist noted a few months afterward, criticizing the “air of cloak-and-dagger paranoia” surrounding the effort.

At the time, Blumberg said he agreed to serve on the study’s review panel to replace his friend, prominent neuroscientist and herbicide critic Andrés Carrasco, who had unexpectedly died. “I wanted to help out for a friend,” he said, on what sounded like a good study. Aside from his travel, he didn’t receive any money for his involvement, he said. He did not know the actual study scientists or how much money was collected.

When asked what he thought about the Factor GMO website still collecting donations, Blumberg told BuzzFeed News by email: “What the FactorGMO people do or do not do is not really my concern.”

A decade ago, Russian researchers created potatoes that borrowed a gene (“kindly provided by Monsanto”) from a harmless bacteria to make the spuds resistant to beetles. The GMO potatoes were approved by the state. But after Vladimir Putin returned as president in 2012, Russia’s anti-GMO efforts kicked off.

At first, Russian biotechnologists noted, a lack of rules for approving more modern genetically engineered crops meant "cultivation and breeding of GMOs, for example in agriculture, is ruled out."

Then in 2015, Putin announced plans to make Russia the world’s biggest exporter of non-GMO food. In an address to the Russian parliament, he said: “We are not only able to feed ourselves taking into account our lands, water resources — Russia is able to become the largest world supplier of healthy, ecologically clean and high-quality food which the Western producers have long lost.” Russia banned GMOs completely a year later. (Europe has imposed stringent rules on GMOs since 2010.)

Protests against #GMO, toxic #pesticides erupt in several countries (PHOTO) https://t.co/OZirWejbW6

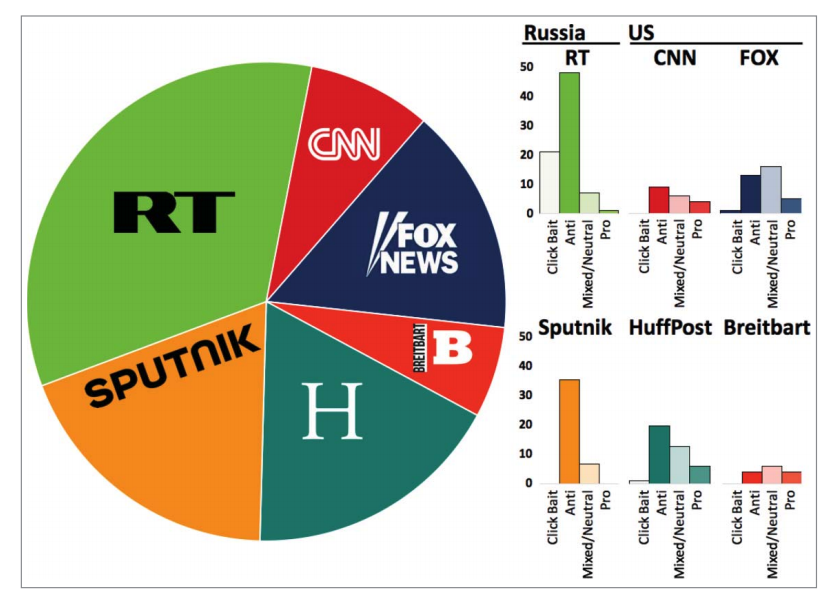

By 2016, RT and Sputnik, the two main Kremlin-owned outlets producing stories in English, were preoccupied by — and strongly negative toward — GMOs, according to a March study conducted by Dorius of Iowa State.

His team scraped the websites of RT, Sputnik, CNN, Fox News, Breitbart, and Huffington Post to find all stories in that year that mentioned GMOs. They found that RT and Sputnik produced 53% of all English-language stories in the study. And their stories were overwhelmingly opposed to GMOs — unlike the US outlets, which produced a mix of anti, pro, and neutral stories on the topic.

“Russian state news gives substantial attention to anti-GMO tropes involving rats, fertility, cancer, and GMOs,” Dorius told BuzzFeed News.

The survey found that RT’s stories often contained scaremongering myths about genetic engineering (such as the headline “GMO mosquitoes could be cause of Zika outbreak, critics say”). “It is typically designed to look like legitimate news,” Dorius said.

In that way, Factor GMO — with its press conference theatrics — seems similar. “Factor GMO seems like a marketing campaign that fizzled,” Dorius said, its presentation intended to raise questions about all previous safety studies and findings.

Polling experts told BuzzFeed News that it’s difficult to know whether these Russian efforts have swayed US opinion about GMOs — particularly because so many Americans are already skeptical of this technology.

Pew Research Center polling from 2016 suggested that 39% in the US thought GMO foods were worse than others. About 1 in 6 people said they cared a lot about GMOs, and most of that group were opposed to them.

Overall, the US scientific consensus is that GMOs don’t appear to be dangerous, a US National Academy of Sciences report concluded in 2016. (The real risk from Roundup was that its ubiquity has led to resistant weeds.) And although glyphosate is less toxic than caffeine, scientists are still investigating it for any health effects, without turning up much.

Nevertheless, people in the US trust scientists on GMOs even less than they do on vaccines, evolution, nuclear power, evolution, or climate science, according to studies by Lawrence Hamilton of the University of New Hampshire. Unlike climate change or evolution, GMOs have not become a matter of Republican versus Democrats politics, Hamilton noted.

But the US fight over GMOs, which has so far played out mostly online and in courtrooms, is about to get political attention. In July, the US Department of Agriculture is supposed to release mandatory disclosure rules for genetically modified food, leaving the decision for the Trump administration on how to proceed.

Factor GMO may have fizzled out because it didn’t get any public traction, and the organizers “just cut their losses,” said Jankowicz of the Wilson Center. (The project’s outdated website states that its funding was “sourced from around the world” and that “a high percentage of the total needed has been secured, allowing us to start the experimental phase in Spring 2015.”)

Alternatively, Jankowicz said, the nebulous status of the project might be intentional. As long as a Potemkin “largest international” study is perpetually in the offing, critics can say that questions still remain about the safety of GMOs. It serves as a model for a kind of fake science meant to inspire cynicism about new technologies and institutions in general, she said. “They get people doubting something, without having to do any work and without any follow-up.”

The nebulous status of the project might be intentional.

Blumberg said he has made no effort to contact Factor GMO since the 2014 news conference.

“I already have plenty on my plate,” he said. He’s one of the handful of US researchers concerned about glyphosate, part of a group that published a “statement of concern” claiming possible hormonal effects from the herbicide in 2016.

Blumberg pointed out that the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) has designated glyphosate as a “probable human carcinogen,” a hotly contested designation amid a federal lawsuit brought by people who claim they developed non-Hodgkin's lymphoma from Roundup. (IARC has reserved the same cancer risk distinction for “very hot beverages” and “wood dust.”) Another court case in California right now revolves around a fight between Monsanto and the state’s environmental regulator over placing a carcinogen designation on Roundup.

That’s all despite numerous scientific societies endorsing the National Academy of Sciences report, which found animals “were not harmed” and that the herbicide brought no cancer risk.

The Factor GMO study may have gone to seed if not for Mary Mangan, a biologist affiliated with the pro-GMO advocacy group Cornell Alliance for Science. In April, Mangan blogged about the disappearance of the project (titling her post “Science Vaporware, From Russia, With a Bad Smell”).

Blumberg told BuzzFeed News that Mangan and other critics of the Russian effort are apologists for the herbicide industry. He compared them to deniers of climate science or the dangers of smoking.

"I wish someone would do this study," he said.

Mangan — who says she isn’t funded by industry — actually agreed. “I would love to see the Factor GMO data,” she told BuzzFeed News. “Whatever Blumberg thinks of me, it still doesn't exist and seems pretty dodgy.” ●