Scientists have looked for the first time at the brain patterns of Islamist radicals, showing that the part of the brain associated with deliberative reasoning is deactivated when a person is willing to fight and die for a "sacred cause" — and that the opinions of their peers can change that way of thinking.

Researchers from the UK, Spain, and the US carried out brain scans on groups of men at various stages of radicalisation for Artis International, a research group that studies the role of "sacred values" in violent conflicts around the world.

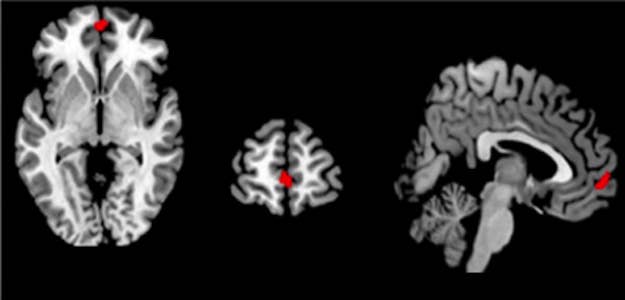

The study, published in the Royal Society Open Science journal, found that when a study subject was willing to fight and die for what they considered to be "sacred values", activity in the areas of the brain associated with deliberative reasoning decreased. Instead, they showed high activity in a different part of the brain — one associated with subjective perceptions of value, such as what a person finds beautiful.

Nafees Hamid, a social psychologist at University College London and one of the researchers, told BuzzFeed News that usually both parts of the brain are active.

"In most people’s day-to-day activities, you have both mechanisms working in tandem. Even if someone’s thinking, 'That hamburger looks really good, I want to eat it,' they’re still thinking, 'It’s a lot of calories and I'll feel bad afterwards.'"

However, when a person is willing to fight and die for a cause, the part of the brain associated with deliberation (their dorsolateral prefrontal cortex) becomes disconnected from the part associated with what they value (their ventromedial prefrontal cortex). When a person is less willing to fight and die for a cause, the two areas reconnect — and that person is open to reason.

The study was based on a sample of 30 men from a Pakistani community who had been selected from a broader group because of the high levels of radicalisation they recorded in a survey. All supported the militant group Lashkar-e-Taiba, which the UN describes as an entity associated with al-Qaeda.

In one experiment, the researchers asked the subjects to identify the extent to which they were willing to fight and die for both "sacred" values (such as not caricaturing the Prophet Muhammad) and "nonsacred" values (such as women wearing the niqab). They then told the subjects that their peers had responded differently — inventing either a higher, equivalent, or lower willingness to fight and die for the purposes of the experiment.

After learning their "peers'" responses, the subjects were asked the same question again. The second time, they altered their answers. Crucially, if they were told that their peers were less willing to fight and die for a cause than they were, the subjects expressed outrage but ultimately lowered their willingness, too.

Simultaneously, the part of the brain associated with deliberative reasoning was activated once more.

"That shows that you can lower people’s willingness to fight and die, and when people’s willingness to fight and die decreases, [the part of the] brain associated with deliberative reasoning [is] activated," said Hamid.

"What we’ve found is that one main vector of influence in being able to achieve that is through people’s perceptions of what other people think."

Asked why the subjects participated in the research, given that it would be used for the goal of mitigating extremism, Hamid said they were willing because it was an objective analysis that "fairly" represents who they are without depicting them as "crazy".

"People have simplistic explanations where they want to say these people are crazy, there’s something wrong with their brains. [Others] want to explain it down to a personality level ... or they want to explain it on a more environmental level. But we knew that it’s at the intersection of a particular person exposed to a particular set of circumstances," he said.

"The neuroscience element adds in a further layer because we’re not finding anything bizarre going on with the brain. There’s nothing abnormal going on in terms of how people are processing things. It’s just normal functions being directed in a particular way."

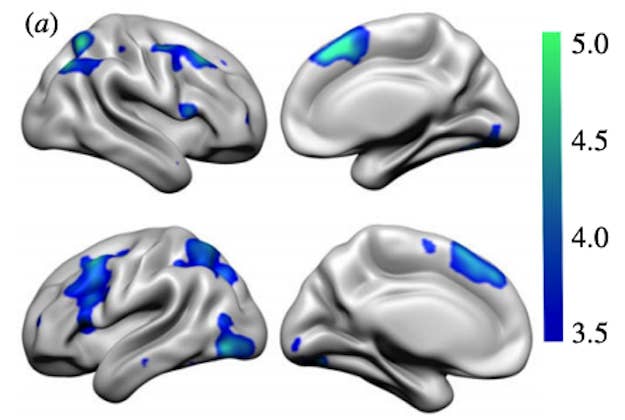

The study follows an earlier part of the research that looked at less radicalised men from a Moroccan community in Barcelona. Using an experiment in which the one Moroccan subject was excluded from a virtual ball game by three "Spanish" players, it found that subjects became more willing to fight and die for even their “nonsacred causes" if they felt socially excluded.

“It’s not that social exclusion creates terrorists, but it creates ... social fissures in society.”

"It’s not that social exclusion creates terrorists, but it creates these social fissures in society where people all of a sudden feel like they have no agency in the current system; they can’t make a difference in the system; they can’t advocate for their or their friends' concerns," Hamid said.

"It’s in those more helpless states, so to speak, that an extremist group can come in and align itself with the identity of the excluded and say, 'We’re going to stand up for you — ally yourself with us and join us in the fight against the establishment.'"

The research has drawn important conclusions for policymaking to mitigate radicalisation, according to Hamid. The first is that social inclusion should be actively promoted at a local level through community organisations that are encouraged to reach out to the excluded, rather than putting the onus on them to become integrated.

The research also indicates that some "counter-messaging" strategies used by governments to discourage people from becoming involved with extremism will have limited impact because the part of their brains associated with deliberative reasoning has been deactivated. Moreover, such strategies do not reach out to the individual.

"You’re trying to target messages towards a particular function of the brain that has deactivated for those values," he said. "And sacred values vary from person to person within a movement. ... When ISIS were trying to recruit people, they had all this mass propaganda, but all of that was there to augment a conversation that people were having one-on-one with recruiters."

The importance of peer group perceptions shows that the support of friends and family is key to preventing people from becoming radicalised, or from relapsing.

"We’ve never been able to make someone change their values; that’s very hard. But we have, with this experiment, been able to get people to lower their willingness to fight and die for those values," Hamid said.

"Their friends and family ... have the greatest vector of influence in reducing [a person's] willingness to fight and die. That is, at least, the first step in hopefully the long run to getting them to drop the ideology to begin with."

The findings of this study were first covered by the Conversation as part of its Insights series.