This is Part 2 of a BuzzFeed News series.

Part 1: Revealed: How Racism, Meth, and Sex Are Combining To Destroy Queer Black Lives here.Part 3: This Is What Happens When Queer People Of Color Seek Help For Meth Addiction

“I woke up and they were pulling a body out of Ed Buck’s house,” says DeMarco Majors. He was watching the scene live on the television news on the morning of January 7, 2019. It was the second black man to have been recovered from the Democratic party donor’s West Hollywood apartment — the second to have died there of a crystal methamphetamine overdose following a hookup. How strange, thought Majors; only recently he had been discussing the first case with his dear friend of 20 years, Timothy Dean.

“I texted him, ‘Did you see this shit?’ I even took a screenshot of the body on the gurney.” As Majors was messaging Dean, 55, he was unaware of what those at the scene knew: The body on the trolley was Dean’s.

Majors’ phone rang. It was a friend up in San Francisco. “He’s like, ‘Tim’s gone. He was at Ed Buck’s house.’” In disbelief, Majors ended the call and phoned Dean’s best friend, Alex, pleading: “I need you to tell me right now that this is a lie.”

“I’m sorry,” replied Alex. “I can’t do that.”

Majors tries to convey the enormity of the loss: the old friend who had long been there for him; the big personality who worked for Saks Fifth Avenue and always wanted to make things just so. The senselessness of it all. That he could no longer confide in Dean, who was far into his own recovery from meth. “Tim was in many of our lives,” he says — a mentor to people facing addiction.

What would make even less sense is how Dean ended up at that address. A month or two before his death, says Majors, Dean had warned him not to go to Buck’s apartment. They were talking about Gemmel Moore, the first man who died there, in July 2017, aged 26. “He said, ‘DeMarco, don’t you take your ass to Ed Buck’s house.’ Tim shows me his phone, all these messages from Ed Buck. It was a lot of messages. He went like this…” Majors performs the phone-scrolling gesture, quickly, to denote how many screens it took up. “I said, ‘I’m not going over there.’ He said, ‘Me neither.’”

But with meth addiction, he says, “You’re never out of the woods.” So although he believes Dean went to Buck’s house to take meth, he does not wonder why. “Crystal has a way of contacting you,” he says.

He stops and looks up.

“I have walked those paths,” he says, “I’ve been on the train to go hang out with somebody and even shivering with fear, [thinking], You shouldn’t do this. And then a moment later, How the fuck am I sitting on his bed without my shirt on?”

Majors’ story answers this question — how meth magnetizes particularly queer people of color – in a series of layers. It leads to the starkest of illustrations. After two hours of talking, he lifts his left forearm. Marks and scars bisect it: across, underneath, stripes of different width and color. Some look like burns. It is too much for him to talk about, for now. Instead he nods to confirm one detail: A white man did this.

Majors is one of four queer people — three black, one Latino — who today, in the second part of this series, describe the underlying causes driving their meth use, the harm the drug caused, and most of all, what lay in wait when they took it during sexual encounters with white men.

Such hookups — where meth and other drugs such as GHB are used to intensify everything — are popularly known as party and play (PnP) in the US, and as chemsex elsewhere. But what is being ignited in these settings, the racism and violence, has been largely hidden, with the only flares fired into the air when a public figure has been involved.

As well as the more immediate, recognizable attacks on a person, what emerges through these accounts is something previously undocumented: the targeted, sustained abuse of individuals over long periods — and the thrill their destruction gives the perpetrators.

DeMarco Majors, 42, stoops to light two candles — for Gemmel Moore and Timothy Dean. “It was two young men who were taken, here in LA,” he says.

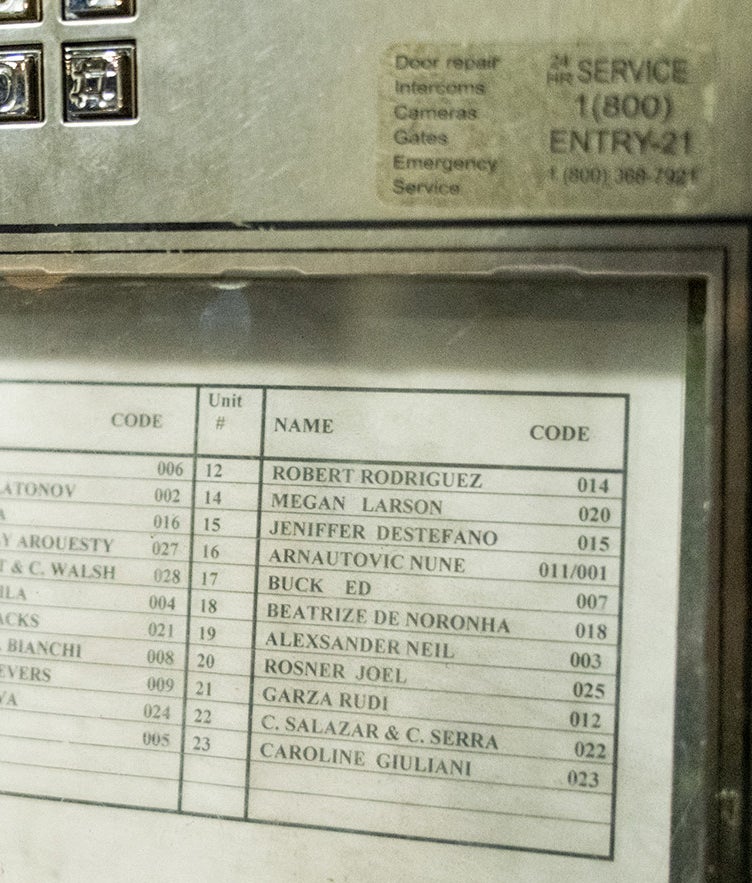

His open-plan apartment is set back behind a security gate in Sherman Oaks, a quiet suburb in the San Fernando Valley of north Los Angeles. Sage has been burning, thickening the air with earthy acridity. “We have to protect ourselves,” he explains. “We’re sitting targets.” What he means by this builds over several hours.

He switches on a lamp beside a small table. “If you go on an app, do you know how many times I'll get asked if I ‘party’?”

His voice is a soft baritone. His looks — tall, muscular, angular jaw — suggest fortitude, and his life, success: a former professional basketball player who appeared in a Beyoncé video, modeled at New York Fashion Week, and after disclosing his sexuality — as a black, gay sports star — was named by Out Magazine in 2007 as one of the top 100 influential LGBT people in America.

But today he is rigid in his chair. It’s been 10 months since he lost Timothy Dean, and grief seems locked into every muscle. “He was one of the most loving, funny characters,” says Majors. “He would laugh and get close to you and put his hand over his mouth and tickle you while you're laughing. You know?”

Majors stops for a moment to breathe. He begins to explain meth’s pathway — how men like he and Dean are propelled into its orbit.

First, he says, there is the growing up black in America. “Men of color always have to be strong,” he says. Majors was raised in a single-parent household in Indiana, with little money. “You’re taught to survive before you’re taught to love.” And if the love you feel is for another man, it can lead to rejection by church and family.

“You’re taught to survive before you’re taught to love.”

“A lot of people would never understand what it’s like to be black — and then black and gay?” he says. This then involves entering the gay scene, “where people tell you ‘love is love’ and ‘equality for all’ and then you’re told on an app: ‘No blacks, no Asians.’”

A community that should provide sanctuary, therefore, instead compounds alienation: a double rejection. “Some white [gay] guys,” he says, “were not taught racism was wrong.” And then meth enters the bloodstream, ripping inhibitions away. “When you are under the influence, that shit is heightened,” he says.

Majors remembers the first hit of meth, in his late twenties, given by a white man. For the first time, he says, “I was not in my head.” Pain and shame were silenced. “I was actually OK with being touched and touching someone. I didn't have to be aware at all moments. It gave me what I thought was freedom.”

The danger, however, lay not only in the people Majors began to meet, but in what meth found in him to feed upon: a trauma buried decades before.

Major says he was abandoned by his mother when he was 13. “I was given away on Christmas Day.” There was domestic abuse at home, he says: fights between his mother and her partner. “My mom asked me if I could stay with my grandfather for awhile.” After a few days she said to come home, so his grandfather dropped him off.

“They didn’t answer the door,” he says. “I found myself sitting on the porch in the snow, with all the lights on in the house, and the TV on.”

His grandfather had been driving around, and looped back to check on the boy. “He saw me still sitting there in the snow. He picked me up and said, ‘I’m never going to let you feel this way again.’”

Majors was raised by his grandfather until he graduated high school. But once he arrived in New York City in his twenties, meth bit. “I had all this deeply rooted hurt, shame, and depression,” he says. Because of its use with sex, often arranged on hookup apps with two or more men, the combination — disinhibition, connection, escapism — was too great to resist. “You end up getting around people and people touching your body that do not deserve you.”

On one occasion, this escalated beyond his worst fears. He went to see someone, a white man, he considered his friend. There were others there who gave him meth and GHB until he lost consciousness.

“When I woke up, the person who’s supposed to be my friend was sitting on the side of the bed weeping,” he says. In the confusion, all he knew was that “I was high as fuck and ashamed and throwing up. Didn’t know that I was out [unconscious]. I said, ‘I’m going to go to the store to get some Gatorade.’” But when he later arrived home, something else felt wrong, physically. “I went to the bathroom and checked myself,” he says. Fearing the worst, he phoned his friend. “I said, ‘Did something happen to me?’” Majors enunciates the response as a slimy drawl.

“He said, ‘Ohhhhh, it was so hot.’”

The words reverberate around the sparsely decorated room.

“I had been drugged and my body used while I was passed out,” he says. Majors remembers how he replied and relays it in a rasping tone that sears with incredulity: “And you let them use my body?”

This was just one occasion. Being a model, a beautiful man on the scene, put him more at risk. “People look at you and are instantly attracted by your outward appearance,” he says. “It’s like, Get the drug in so I can get what I want. These people will harm you at any and every opportunity they can.”

At the time, he could not consider what was behind it — racism or otherwise — because of the distorting effect of meth, disguising cruelty in the fog of need.

“You want to be loved, but the truth is you don’t know what love is. You only know what feels good.”

“You’re either trying to survive,” he says, “or to keep people at a distance — even though you want them so close. You want to be loved, but the truth is you don’t know what love is. You only know what feels good. Because you’ve dealt with so much emotionally, the little engagement you get with another human being? Your perception says, ‘This is good’.”

Often it wasn’t even the sex he craved with meth. “It was the companionship,” he says. In those rooms of uninhibited strangers, “you could actually talk to people.” He describes the inner voice, driving him to those houses: “Please just give me these next couple of hours where I can just feel like a human being.”

Now, however, he sees it differently: “I was numbing myself.”

Much of what he experienced percolated for years before forming a clear perspective, of the abuse enacted upon him and others, nuclearized by meth and racism.

“A lot of people have the drug around because it was the lure — they couldn’t get the guy they wanted on their own,” he says. He remembers a white guy who had been gorgeous when younger, but was horrifically beaten in a homophobic attack — a baseball bat to the face — that also destroyed his confidence. But when he found meth, “he could get over [to his house] whoever.” In his case, it was black men. Only later did Majors come to regard this behavior pattern as predatorial. But he is insistent on understanding what lies beneath.

“Hurt people hurt people,” he says, not excusing the white gay men responsible, but seeing the context. “This community was built on hurt.”

As Major talks, he becomes concerned that the conversation itself could be dangerous. I try to reassure him that I’ve interviewed many who have suffered violence and trauma, including victims of torture. At the utterance of this word, he interrupts.

“It’s just not something I’m ready to talk about,” he says. It is then that he bends his left elbow upwards and the scars become visible. “I know what it’s like — for someone you think is in love with you, but the drug is more important.” He changes the subject, later nodding when asked if a white man was responsible.

“I don’t blame this on him even though…” he begins, without saying who or what or why. “One day I’ll be ready to talk about it because every single day…”

“You see those marks?” I ask.

“Yeah,” he whispers. “I’ve never covered it up.” Instead, he says there were lessons from it that contributed to finally bringing him away from meth. Ultimately, the momentum to stop using came from one motivation: “I wanted to be loved.”

He tries to help others now. He talks of a friend who video-phoned him recently while high on meth. Majors kept him talking for hours, just to stop him going out and meeting harm. The wider discussion, he says, also needs to become about solutions: tackling the mental health problems that underpin everything and the racism compounding it.

But six months ago, just four months after Timothy Dean died, Majors lost the person he had fallen in love with, a Puerto Rican man named Jesus. “One of the most beautiful men I ever laid eyes on,” he says. “The first guy that I loved — really, deeply loved. All I wanted to do was take care of him.” But Majors could not stop what was about to happen.

“He was partying with some guys,” he says, “and I don’t know all the details, but as he was dying, the guys were so afraid because there were drugs in the house [that] they didn’t call the police. They left him for dead.” As he begins to talk, his fury rises as if confronting those men: “I don’t give a fuck if you did the drug. Call [911]! You could have cleaned up the house and ran. But you let him die.”

He breathes deeply. His voice drops back, quietening into stillness.

“That broke me,” he says. “So many in our community are prepared to let people die.”

Others, however, are engineering it.

A skinny, Latino 21-year-old with bright red hair is running through traffic in downtown Los Angeles. It is 8 a.m. Joey Valladares is barefoot, terrified, weaving between the cars, unsure where he’s going. Cars beep, irritated. He will keep running like this until 4 p.m.

As the hours elapse, Valladares’s physical and mental state worsens. People laugh at the strange twitchy figure darting across the sidewalk. Dehydrated, he tries to buy water from a branch of Target, but they ask him to leave. Café owners refuse him tap water. Valladares knows from the laughter and the looks what he has become to the world: another meth head. Untouchable.

The realization jolts him, more so than knowing that the men who fed him meth daily in exchange for sex would be excited by this sight. Eventually, a restaurant worker comes out of a shop with water for him. Valladares’s hand is shaking so violently that he spills it before it reaches his mouth.

Later, assured that he has sunk to an unscalable depth, Valladares will stand on an overpass staring at the traffic below, deciding whether to jump.

Two years on, Valladares sits cross-legged in a meeting room, recalling that day. We are still in downtown LA, but this time in the offices of the Act Now Against Meth Coalition. It is about to be relaunched by the Wall Las Memorias Project (an organization for the health concerns of Latino LGBTQ people) due to increasing concern about meth’s spread among Latino communities.

“I couldn't stop crying. It really felt like people wanted to see me hurt myself, and I remember thinking, Should I just give them what they want? ”

“I remember sitting down on the sidewalk,” he says. “I hit my limit and just cried. I couldn't stop crying. It really felt like people wanted to see me hurt myself, and I remember thinking, Should I just give them what they want?”

Valladares is 23 now — nonbinary, femme-presenting, and a drag performer — and uses a variety of pronouns, so is happy to be referred to as "he," "she," or "they." A ring hangs from his septum. The once bright red hair is now long and a muted auburn. White stones dangle hand in hand beneath the collar of a high-neck shirt.

His father was a meth addict. His uncle killed himself while high on the drug. His brother is in prison for a meth-related crime. The El Salvadorian family never thought young Joey would succumb too — he was the smart one. The language he uses is evocative but delivered flat in tone, as if trying to dampen the intensity of his words.

“I had just got out of an abusive relationship,” says Valladares recounting his first time with meth. “And I met this guy and he offered it to me to smoke. The second I smoked it, it was something completely different — more intense. I really felt a change in me.” The effect of that change, ultimately, was what meth did after the high plummeted: roaring back at him, demanding repetition. “It was a need. It wasn’t like, I want to do this. My body needed it. Not so much me.”

Valladares was new to living in Hollywood and, not knowing many people, downloaded Grindr, partly to meet others, but also to find meth. “It was crazy how easy it was to get, especially for free,” he says. Except that there was a price to pay: “You knew what these people wanted.” With the drug so available and the craving so intense, Valladares developed a daily habit.

Grindr is not just for gay and bisexual men. Because trans and nonbinary people also use it, so too do those who want to meet and have sex with gender-diverse individuals. This includes men who would self-define as heterosexual. So for Valladares, there was a market: men, mostly white, who wanted femme-presenting sexual partners and were prepared to pay with meth. Some were gang-affiliated. Many became regulars, feeding Valladares the drug over many months in what he came to understand was a systematic attempt to control and harm him.

“The main person who was giving me drugs was white,” says Valladares, explaining that not all were, but many. The drip-feeding of the drug combined with the dehumanizing way they reduced him to a sex object later formed his conclusion about what was happening to him and other black and Latino youths.

“It’s targeted,” he says. “If you are a cute Latino boy or cute black boy, these people will keep you around like you’re their pet.” And like a dog with a cruel owner, “if you do something to cross them, they will throw you out like [you’re] nothing.” Submission was expected and enforced, combining misogyny with supremacy: Valladres had to play the willing, grateful Latino girl.

The white men acting as the owners had money and homes. “But the other people of color I met while on drugs were going from spot to spot, homeless. But there was this wealthy person ‘taking care’ of them.’”

That care was always just power, however: They had the drug. On one occasion, Valladares was so desperate for meth he agreed to present as masculine for a white gay man in a luxury apartment downtown, removing all makeup and nail polish, hiding his hair in a beanie, all to score the meth. “That guy’s whole thing was men of color coming over and doing drugs with him.” As Valladares was leaving, “He said, ‘I’m having this black gangster guy come over later.’ That was his thing. People of color are sexualized.”

“If you are a cute Latino boy or cute black boy, these people will keep you around like you’re their pet.”

On the surface, the trade of sex for meth seemed simple. Except unlike with money-for-sex arrangements, here there were no boundaries. What this means, for example, is “asking me to perform oral sex on them for an hour straight and if you stop for a second, it’s like, ‘OK, well, we have to do it all over again.’”

They assaulted Valladares. “During sex acts, even telling them that I didn’t want to do something, I was forced to if I wanted the drugs.” And they used both meth and GHB — the highly potent anesthetic that easily causes unconsciousness — to render Valladares defenseless.

“These people wanted me to get to that point where I didn’t have a say,” he says, explaining that they would “wait for that moment for me to be out [semiconscious] to do something to me.” He would come round to find someone having sex with him. Often they would be angry that Valladares was now fully conscious. But there seemed to be no alternative, no matter how degrading: The physical cravings for meth dictated everything.

“I look back now and think, Wow, these people were really just watching me hurt myself.” An obvious example was giving him “way too much meth for one person.”

This happened so regularly, every day over the course of a year, that after several months, those men were witnessing Valladares crumble — while continuing to feed him the drug. “People got pleasure seeing me slowly die,” he says, looking down for a moment. “They saw me get skinnier, and losing the function of speech because I was getting high every day, staying up two to three days.”

The physical effects were beginning to ravage him.

“I saw what was happening to my eyes, my face,” he says. “I was 25 pounds skinnier. One time I remember being so high and my mouth so dry I had peel the inside of my mouth off my teeth. I would get canker sores maybe once a week from how dry my mouth was. I wasn’t eating, I wasn’t sleeping, just pushing my body to a point where I was awake so long that I would just…” Valladares snaps his fingers. He would fall asleep in a moment, anywhere.

By the end, Valladares was so paranoid that he became almost affixed to his bedroom window, keeping constant lookout. The day barefoot in downtown was the end. His decision, therefore, was either stop, die, or be killed. He rang a friend, admitted his meth addiction, and wept.

Recovery was tough. “I was very twitchy for the first few months,” he says, “very insecure of how I was talking, how I looked.” He didn’t go to a rehabilitation center or have counseling but coached himself through it like an athlete whose life depended on winning. Now, when he talks to young people, in his role as a volunteer for the project, he can offer advice. “There are people out there that will care about you,” he says, but, “ultimately it has to come from you.” His career as a drag artist is taking off now too, and he performs all over the city.

But Valladares is left with meth’s rubble: memories of what was done to him, of what he was prepared to do. “It damages your soul,” he says. Sometimes his speech or motor skills still fail. Valladares also lives with the imprint of the other queer people of color he met, who remain trapped, and with the dread of what fate they could meet. He speaks quietly, with a somberness that hints at it.

“Only some of us stopped.”

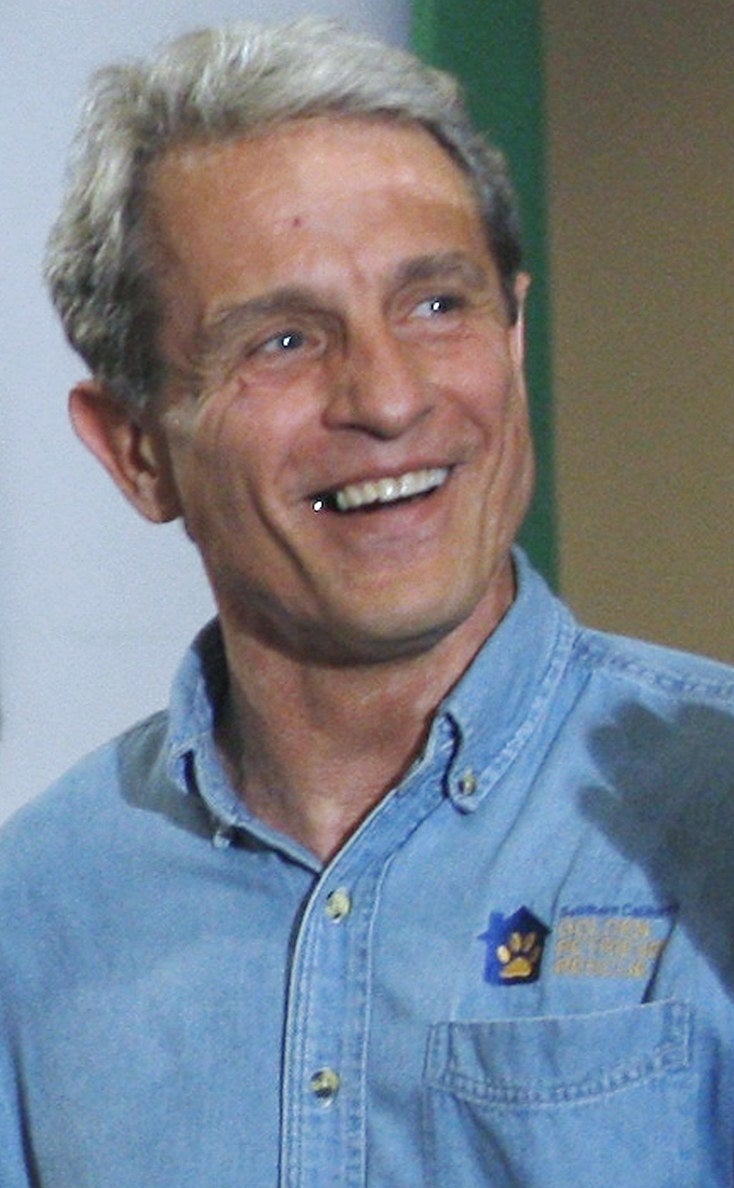

Kenneth knows that stopping kept him alive. The black 57-year-old choreographer and dancer (who asks for his surname not to be included) quit almost 20 years ago, after five years of inhaling and injecting. He saw meth’s genesis, when it was swirling through white gay circuit parties — well before it found most queer people of color.

We sit in his cozy West Hollywood apartment in the dipping sun of late afternoon. When asked about some of the difficult situations meth brought him to, his answer bolts out.

“You mean outside of having a gun pointed to my head?”

He begins to elaborate on that situation, “It was like, Oh my god. He’s high. I’m high. What the fuck is about to happen? He was white. He wanted me to take my shoes off and throw them across the street. It was crazy. Crazy town…” but rather than filling in the blanks, he segues to other memories.

“I had two situations where I blacked out, so I don’t know what happened. One, I woke up and I was tied to the bed. My arms were tied to the post, and to this day, I don’t even know how that happened.”

“I had two situations where I blacked out, so I don’t know what happened. One, I woke up and I was tied to the bed.”

His voice falls to a whisper as he recalls his response. “I didn’t say a word and I…” He starts hitting the back of one hand against the other, as if beating out the sadness and frustration. “[I had] no voice. All I could say was, ‘I have to go.’”

There were other incidents of white men verbally or physically harming him — memories now dimming in the gloaming of the past, but together providing certainty that there is nothing unique about the allegations against Ed Buck. The political donor is, he says, “not the only one because the men I dealt with were not Ed Buck.”

None of this was supposed to happen to Kenneth. White men seemed to be the answer. As he begins to explain, he uses his body to illustrate.

Kenneth is 6-foot-3 and bald, with arms like Grecian balusters — developed over decades in the gym. His arms talk: elbows cocked out, hands into fists, when illustrating the tough, dominant image he has worn for much of his time in white gay enclaves — jokily referring to “imaginary lat syndrome.” He then clamps elbows in tight, with hands and wrists rotating, fluid, when conjuring the boy he was, and the man he tried to hide.

“I was raped at 9,” he says, suddenly. “Abducted off the street.” The perpetrator, in his hometown of Detroit, was black. The trauma defined much of what was to come: seeking safety and escape, but instead finding white men and meth and danger. He remembers what he was wearing that day.

“I had on my fancy…” he stops, grabbed by the memory, “my favorite brown and blue shorts. I was nice,” he says, referring to the smart little outfit. There was something about that 9-year-old — that he was or would become gay — that the abductor recognized.

“He knew,” says Kenneth. “He saw me and that I saw him see me.” That single moment, he came to believe, made him prey. Kenneth jolts himself back into the present, into adult perspective. “So I had to protect myself from that moment ever happening again,” he says. From then on, he had to hide who he was.

But the homophobia growing up in Detroit in the 1970s was too great. “I was very effeminate,” he says. “Nobody including my mother and father knew what to do with me. I was publicly humiliated for being a ‘sissy,’ because black men were not supposed to be that. Everybody who beat me up, beat me up for being a black sissy. I had a whole race of people telling me I was going to hell and I was not enough — I wasn’t masculine enough.”

When Kenneth moved to New York in the 1980s to study dance at the famous Juilliard School of performing arts, he found white gay men. And from then on “I exclusively dated white men,” he says. “I rejected my whole race because I was so afraid that they can hurt me so much.” He went to white gay clubs, white gay circuit parties, all for one reason: “I’m safer here.” He also discovered working out. “Because then I didn’t need a verbal armour. I had a physical armour.”

But the quest for protection and safety instead led him to meth. At the Sound Factory Bar — a predominantly white, gay, house music club — in 1995 he started dancing with two white men. They gave him a bump that he took to be cocaine but was actually meth. Now high, he turned to look at the mass of bodies dancing. “And I felt like the biggest, blackest motherfucker in that place.” He distills this further: “Nobody can touch me.”

Except what happened was the drug exacerbating and unveiling the racism of white men.

“Everybody’s inhibitions are gone,” he says — including his own. They would call him the n-word, but rather than saying something he would play along. He adopts a hardman voice. “You wanna call me a nigger? Alright, white boy, wha’chu want? Come on, white man, you want me to fuck yo’ white ass?”

It took years to realize there was no real power there, that white men had it and meth had it, a brick tied to the ankle, dragging him to places he never would have found. “Being,” for example, “in a piss-filled mattress for four days, letting people pee.”

“Young black men are dying. And it looked like nobody cared.”

Even after five years, when he came off meth, the hardwired roles he had played took time to unlearn. The butch black sex stud they desired, exaggerated by the meth, imprisoned him. “Seriously, I was like, If I don’t fuck for four days, sober, they’re not going to want me.”

Therapy has helped, both individual and group: helping him reach back and discover what had been erased. He wiggles his fingers. The nails are short but coated in dark varnish. “I never painted my nails before,” he says. Only recently has he dated another black man. Finally, he says, after more than half a century, “I’m finding more freedom in who I am.”

Meth is not responsible for everything, he says. Not for the way he has been treated by white men; it just lit what was there: his past, his need, and the racism that predates everything and continues to roar through America. He mentions Trump and the cages in which Latino migrants are kept. He stops, returning to Gemmel Moore and Timothy Dean, and the drug — the weapon — that threatens many more.

“Young black men are dying,” he says. “And it looked like nobody cared.”

Thomas Davis’s eyes flicker up to the right as he recounts the numbers of friends — young, black, gay men — he knows who have died from crystal meth. Six? Is it six? He tries to count as we sit in a Starbucks in West Hollywood. Does he include acquaintances? He begins to add those who overdosed, too.

He remembers the call from a hospital, a voice telling him about the man he had had sex with a few days earlier, who had then been found overdosed in the street and was now in a bad way, and could he come? There was no one else they could contact: He only had Davis’s number stuffed into his pocket.

Then there was the friend, a fellow professional dancer, exceptionally talented, who used to hit meth hard, who had a heart attack in the middle of a performance. In the middle of his thirties. No one will see him dance again.

There were so many. Young black men who died from meth and GHB during sex; deaths known about by others in Davis’s circle but who were too locked into the same addictions. “People would OD, and it never seemed to stop any of us,” says Davis. Denial would kick in. He conjures the self-soothing lies: They just did too much; they shouldn’t have been shooting up; it’s not going to be me.

But for some, it was. And now, finally, aged 27, Davis has quit. He knew both Gemmel Moore, the first to die in Ed Buck’s home, and the man who fled and went to police. It was Moore’s death that helped persuade Davis to seek help. “He was a really, really sweet guy,” he says. “It broke my heart.”

He looks down at the table in the Starbucks in West Hollywood. He has a goatee, baggy jeans, and the svelte elegance of a dancer. “It changed a lot of stuff for me,” he says, “because people aren’t going to care that this is happening to us.” By “us” he means black gay men. Moore was just “the one that made the news.”

The man who called 911 and prompted Buck’s arrest is named in court documents only as Joe Doe. “He and I have hooked up a few times,” says Davis. “He OD’d twice when he was over there [at Buck’s house], and the first time he and I were hanging out was literally hours before.”

Weeks later, Davis saw him again. “He was telling me what happened,” he says, that after shooting up, “he crawled and dragged himself out and got himself to a hospital.” The trouble, according to this man, was, “He went back [to the apartment] because that was the place that he was staying, and then it happened again.” What Davis means is the man had nowhere else to stay.

“I’ve always called meth the lonely person’s drug. It’s our way of self-medicating. Numb the pain by any means necessary.”

By the time of this conversation, however, Joe Doe had gone to the police. Davis says he encouraged him also to seek help for meth addiction, but remembers what he was thinking: “I really hope you don’t OD before they get this guy in jail.” Despite this, he and Joe Doe continued to have sex and use meth. “It’s literally insanity,” he says of the drug’s power. “When you realize how much this is affecting how many of us, it’s mind-blowing.” (When approached for comment by BuzzFeed News, Buck’s lawyer did not respond.)

Davis tried the opposite of Kenneth: Tired of racist encounters, he increasingly sought out other black men for sex. But meth was still encircling those experiences, bringing danger and fear. He remembers a PnP orgy in a trap house. “There was a party going on in the back bedroom, but a guy started screaming out front because [another] guy was shooting him up and missed his vein and people were panicking and freaking out. It was pandemonium.”

On another occasion, a guy Davis met on the street who took him back to his motel for sex and meth became increasingly paranoid. An argument ensued. Later, he overheard the man on the phone “talking about the gun he has in his bag,” says Davis. “I was like, Dang, he could have easily just…” Davis makes a pow sound: gunfire. “There were a lot of situations where it’s a miracle I wasn’t harmed.”

Poverty only exacerbates this. With no money for the high rents LA demands, Davis lived with a man for weeks who expected in return that Davis take meth with him. As with Valladares, it meant no boundaries. “I would wake up and he’d have music blaring and just be walking around naked and it’d be so cloudy in there,” says Davis, referring to meth smoke. There was no escaping the drug. “I was immersed in it.” And sex was part of the deal. “If he wanted me to, I’d be sucking his dick,” says Davis, but mostly “he just wanted me to be doing [meth] with him.”

Davis eventually found somewhere else to live, but during that time they would talk, and acknowledged a shared need being met: They were both lonely.

“I’ve always called meth the lonely person’s drug,” he says. “It’s our way of self-medicating. Numb the pain by any means necessary.”

Davis attributes part of this pain to the start of his life when he was adopted into a white family. Being a gay, black, adopted boy in small-town Colorado forged a sense of abandonment compounded by alienation — a twin wound that flourished in a world of racism and homophobia. “I don’t feel like I belong,” he says. Connecting with men through sex heightened by meth, therefore, seemed the antidote. “I would feel really, really validated — desired,” he says. “It felt like being wanted.”

The absence of that feeling, acute enough to demand the most extreme remedies, underpins not only Davis’ story but also Kenneth’s, Valladares’s and Majors’. It surfaces so often, as to point far beyond coincidence toward an explanation, and perhaps, to those responsible.

But as Davis grapples with recovery, a question remains, one that relates to the other queer people of color still out there, rejected, and driven to chemical relief. “Now that Ed Buck is in jail,” he says, leaning forward onto his elbows, “what are we doing to actually help people that are going through this?”

His eyebrows dart up, demanding an answer.

“Nothing?” ●