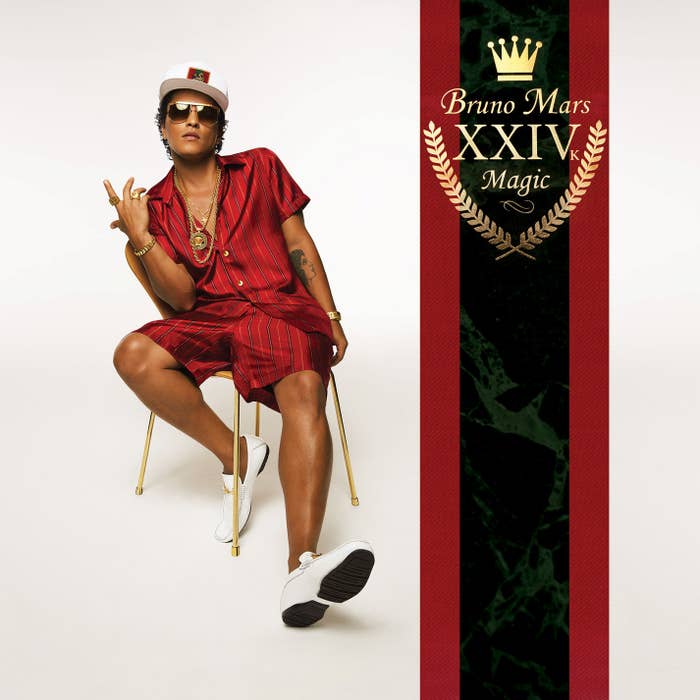

Bruno Mars is everywhere. He’s notched seven No. 1 singles, more than any other male artist this decade. He’s performed at two Super Bowls, he’s an inescapable radio presence, and on Sunday night he won all six Grammy Awards he was nominated for, including the major categories of Record, Song, and Album of the Year (for his single “That’s What I Like” and 24K Magic, his third album). Yet at the same time, his musical presence is like sonic wallpaper: It’s everywhere, but without generating much in the way of serious critical attention, memes, or controversy.

Mars is part of a lineage of artists — like early, “Hero”-era Mariah Carey — whose music dominates the radio, but who are relatively boring as pop stars in and of themselves. The mixed reaction to Mars’ sweep at the Grammys is about the closest he’s come to being an object of cultural controversy, and the conversation around it was still much less about Mars or his music, which very few people seem to actively dislike, than about the other artists who were passed over.

Billboard recently noted that Mars took four years off between albums without losing momentum — effectively because nobody noticed. His album releases aren’t persona-driven pop events like Justin Timberlake’s; he’s not a tabloid fixture like Justin Bieber; he doesn’t sing about narcotic effects and relatably bad decisions, like the Weeknd does. Mars is, as the New Yorker’s Amanda Petrusich recently put it, paradoxically overexposed yet overlooked.

Lately, the conversation around Mars has turned toward his nostalgia for past musical moments and styles. And this focus on Mars’ retro persona has taken hold, at least in part, simply because he’s left a vacuum. By design, he is not a narrative-crafting pop star. “Don’t get me wrong, the fact that people want to talk about me or my music is incredible,” he told NME during his last album cycle. “But to me it’s just, ‘Play the record and you’ll get everything!’ That’s me.”

That emphasis on his records as providing a kind of straightforward transparency — also evident in his videos, which mostly feature him as a performer, either sitting at a piano or dancing — hints at the way Mars has constructed his stardom around musicianship: a dedicated pop perfectionist and curator, rather than a celebrity who happens to sing. This is most evident in the unapologetically corny, retro style of hits like “Treasure,” “Uptown Funk,” and “Finesse.” And it’s Mars’ enthusiastic, earnest embrace of so many different pop eras and styles, as well as his multiracial identity, that makes him an artist with an inherently broad appeal to a large and varied audience — including notoriously unadventurous Grammy voters. That kind of flexible pop presence, in an age when hip-hop has become both the most popular and arguably the most artistically innovative musical genre, is both Mars’ greatest asset and a target on his back.

View this video on YouTube

The 1992 KOMO News report on 6-year-old Bruno Mars, Elvis impersonator.

Mars famously performed as an Elvis impersonator in his childhood, a biographical fact now used as early evidence of his retro tendencies. The 32-year-old was born Peter Gene Hernandez in Hawaii, to a Puerto Rican and Jewish father and a Filipina and Spanish mother, who trained him to play a mini version of “the King.” They performed a variety show for tourists at hotels; in a 1992 video, you can watch his dad backing Mars in his doo-wop revival group, the Love Notes, while his mom sings the girl group hit “Tell Him.”

It’s not incidental that even in the ’90s the family was performing retro Elvis songs, girl group pop, and doo-wop, all melodic crossover genres — accompanied by straightforward showmanship — that could be enjoyed by the widest possible audience. Growing up, Mars had trouble fitting in because of his multiracial identity, and has since spoken about the difficulties of that in-betweenness, which has informed what would become his current musical persona.

In fact, the stage name “Bruno Mars” grew out of professional necessity: Mixing a childhood nickname (Bruno) with the otherworldly undertone of “Mars” helped him transcend stereotypical racial categories in the music industry. When Mars first tried to get a record deal in LA in the aughts, executives wanted to sell him as a Latinx artist; perhaps he could sing in Spanish. “Enrique's so hot right now,” he was told. But with the music that established him as a Top 40 fixture, Mars turned instead to crossover soul-pop.

Mars first became famous as a solo artist with the kind of pleasantly radio-friendly hits — “Just the Way You Are,” “Marry You,” and “Grenade” — that Charlie Puth or Shawn Mendes could’ve sung. But he was always interested in musical sentimentality and nostalgia as themes. In the “Just the Way You Are” video, he sits with a girl on a couch, and they get drawn as cartoonish doodles that emerge out of a cassette tape; the video ends with him playing the piano for her — and us — in his trademark gray fedora, one that evokes sophisticated Frank Sinatra urbanity via Michael Jackson. And in the music video for “Grenade,” there’s a big, heavy piano that he carries around and up a street — like a pop Sisyphus — to symbolize the song’s rather graphically masochistic lyrics about taking a bullet to the brain.

Mars has said that he felt creatively stifled during the creation of that straightforwardly sweet debut album, Doo-Wops & Hooligans, which came out in 2010. (He was defensive about accusations of sentimentality; “If you can't hear the sentiment, as sappy as you want to call it, then maybe you're a piece of shit,” he joked to Billboard.) The shift between that debut and 2012’s Unorthodox Jukebox, an album whose title announces it as a project of unconventional genre-hopping, was a result of him refusing record company directives. “They made me change a couple of things on [Doo-Wops] and I felt disgusted about that. I didn't do that on this album,” he explained. “If I can't be me doing it, I'm not going to have any fun … I'm going to feel like a circus clown onstage, selling something fake.”

The first single off of Jukebox was the No. 1 hit “Locked Out of Heaven,” which Mars later revealed in a GQ cover story was about the female anatomy, in an apparent attempt to sell himself as a younger, edgier artist. (Some of his lyrics have since been described as creepy or brutalizing.) “Locked Out of Heaven” also instigated the “borrowing” or “stealing” narrative that has since dogged Mars’ career. (“BRUNO MARS STEALS FROM ‘THE POLICE,’ NO CHARGES FILED,” went one headline.) Though the song was clearly and intentionally inspired by the Police, Mars was framed as “admitting” that he had channeled the group’s style. Of course, many pop stars, from Rihanna to Lady Gaga, have inspired debates about sampling or sounding like older hits, but most have also developed more contemporary personas and styles that protect them from criticisms of borrowing.

Mars’ affection for pop’s back catalog was on clear display in the ubiquitous top-five hit “Treasure” — which sounds like a remake of Michael Jackson’s ’80s disco-indebted “Pretty Young Thing” — and maybe most of all in the massively successful single “Uptown Funk.”

“Uptown Funk,” which pays contemporary homage to funk and disco, is in fact about using music to bring people together; Mars’ sincerest desire is to “funk you up.” The video for the song was shot in a studio backlot as “a retro-spectacular view of Hollywood’s view of New York City,” as one article put it, drawing on collaborator Mark Ronson’s memories of growing up at 90th and Riverside, as well as Mars’ father’s Bronx origins. But the video’s New York streets are not like the potentially dangerous ones depicted in, say, Jackson’s ’80s video for “Bad.” Instead, they’re more like an imagined safe space for anyone who’s feeling the beat to practice their dance moves.

Mars’ latest hit, “Finesse,” has sparked yet another conversation about his fascination with bygone styles of pop, this time more explicitly around the question of cultural appropriation. The single sounds like a remake of a new jack swing Bobby Brown song, and that retro-ness is explicitly brought out in the music video Mars made with Cardi B (featured on a new remix), which recreates the stage and aesthetics of the ’90s Fox sketch show In Living Color.

But Mars’ choreographed dancing — he more or less took the Fly Girl role — specifically updated the new jack swing dance style with a different kind of hip-hop subtlety. And his look in the video aligns him less with the shirtless sexiness of Bobby Brown than the oversized Fresh Prince style of Will Smith, another artist both dismissed as corny and yet beloved for his crossover rap. The video works as a kind of shorthand for Mars’ whole career, in which a carefully calculated mixture of old and new insistently confuses pop’s established categories of race, gender, and musical authenticity.

Despite Mars’ embrace of old-fashioned showbiz pizzazz and influences like Prince, Jackson, and now Brown, he is also crucially unlike these artists because he doesn’t have the same transgressive cultural effect. Mars’ masculinity of open-necked floral shirts, pinky rings, and pompadour — which he recently described as an homage to his “Puerto Rican pimp” father — and his general performance and musical style, is often perceived (and enjoyed) as shamelessly unhip. Both Mars haters and defenders inevitably bring up his corniness.

Musically speaking, corniness is usually associated with whiteness, imitation, or derivative crossover. The critique of Mars as merely a “soundalike” suggests that he relies on nostalgia or other artists’ innovation to do his work for him. But Mars’ style is more than simple mimicry. As Latina magazine recently noted, it serves as “an ode” to brown masculinities, an especially noteworthy statement in the Trump era.

Both Mars haters and defenders inevitably bring up his corniness.

Not everyone sees it that way. Tyler the Creator dissed Mars and rapped about stabbing him, and in 2013, after Mars won two VMAs, Kanye West accused MTV of using him “to gas everybody up so they can sell some product with the prettiest motherfucker out!” (West has since apologized.) These insults hint at the usual opposition between masculine hip-hop authenticity and supposedly feminized pop artificiality. Mars is arguably unthreatening to older, whiter audiences, in a way that separates him from black artists of past eras and current hip-hop stars who epitomize groundbreaking coolness. His embrace of unembarrassed, choreographed showmanship is clearly at odds with current trends. And the backlash to Mars’ big win suggests that his retro-spectacular style is in fact threatening — to established expectations for how “cool” artists of color (especially men) should express themselves.

Even before the Grammys, there was widespread critical ambivalence about the gendered imbalance of this year’s nominees, and about Mars’ potential sweep shutting out hip-hop artists like Jay-Z and Kendrick Lamar. “But when in doubt, remember that this is the Grammys,” Pitchfork warned, and “Bruno Mars’ mix of musicianship, showmanship, and crowd-pleasing corniness could ultimately carry the day.” Lost in this opposition of hip-hop against pop is the fact that 24K is, as Mic noted, the first R&B album to take home Album of the Year since Ray Charles in 2005. And elided in the binary of black and white is Mars’ Latino identity. (Others have rightly noted their disappointment that “Despacito” — a Spanish-language, globally dominating hit — was overlooked in three categories, raising important questions about the US-centric provincialism of the Grammy awards.)

Perhaps because he doesn’t sing stereotypically Latinx music, and his multiracial identity precludes “picking sides,” Mars’ win hasn’t really been framed as a win for Latinx or Asian-American visibility. And unlike Camila Cabello, who spoke about her immigrant identity in a speech about DREAMers, Mars made his speech, as always, about the music itself — seemingly the one space where he can represent himself on his own terms.

He dedicated his award to the iconic black producers — Babyface, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, Teddy Riley — who have influenced him, and ended on a note about learning the unifying power of music as a 15-year-old performer: “I’m in front of a curtain and I’m singing songs, and my job was to entertain a thousand tourists,” he reminisced, chuckling. “I saw people dancing that had never met each other, dancing with each other, celebrating together. All I wanted to do with this album was that, and those songs were written with nothing but joy.”

Mars’ self-presentation as an earnest, joyful musician seeking to move people through the transcendent embrace of his songs has made him a universal presence, and in turn a contested symbol of universality. And now Mars, in sparking a mini culture war, actually has a dramatic pop story to contend with. But if the past is prologue, he’ll just keep on singing his song. ●