As a Wall Street investor, I peaked around sixth grade. A class stock-buying project empowered me to offer stock tips at the dinner table and my father humored me by buying a few shares. For a few glorious months, I was a Master of the Universe, dispensing sage wisdom about awesome companies like The Gap and The Limited and, especially, the growth possibilities of Claire’s Boutique.

But after taking a big hit with Liz Claiborne, I lost my taste for the market, committed myself to Hypercolor and slap bracelets and re-commenced ignoring all things financial for the next few decades.

Now I live in San Francisco. It’s impossible to miss the chatter about tech IPOs. It’s a global obsession, even: A few years ago, I was standing amidst some ruins in southern Turkey when two Americans began an animated conversation. Discreetly sauntering over to the broken urn at their feet, I heard two unmistakable words: “LinkedIn” and “overvalued.”

Right now, of course, all anyone can talk about is Facebook, the mother of all tech IPOs. What does it mean for mere mortals, though? What is “public” about this “initial public offering”? Can anyone buy a share? The more I thought about it, the more it felt like I should own a share: I use Facebook, dodge Google buses every day, once lunched at YouTube and own at least three Apple products — so how could I not purchase at least one share of Facebook?

Quick primer: The essential logic to an IPO is that when a private company wants to mature — raise money, get respect and give its insiders a chance to cash out (as detailed in this Marketplace Explainer) — it shifts from divvying up its shares among employees, friends, investors, etc. to trading with the public.

There are long answers and short answers to why regular humans can't just waltz up and buy a share of Facebook, but the gist is that its 377 million shares have to be divided amongst those initial shareholders first. The game is to be one of the those guys, cashing in when Facebook hits the general market on or around May 18th.

For us, it’s important to try to lock down a share at the price Facebook has announced — somewhere between $28 and $35. Once the bell rings on the morning of the Facebook IPO, any human with a keyboard and an E*Trade account can buy shares — since the price, at least in the first few days, will be highly inflated.

Unfortunately for me, the easiest route to a Facebook share is a (real) friendship with a Facebook employee or to actually be a Facebook employee, and I am not a friend of Facebook.

My pal Omar though has worked at both LinkedIn and Zynga — two of the most highly publicized tech IPOs over the past few years. Maybe he could help me?

me: hey so let's say i wanted to buy one (1) Facebook stock

how would i do that?

Omar: you mean, after they IPO?

me: after or before

i just want ONE

Omar: haha

well, you can't do it beforehand because the shares aren't on a public exchange yet

there were some available on the second market

(ex-employees wanting to cash out early)

but facebook put a stop to that

me: ugh. is there a third market?

No, Omar gently told me, there was no third market. But let’s go back to the second market. What is it?

Before a company decides to go public, increasingly, people are trading those early private shares on special websites. Business has been brisk, with over $5 billion in deals done via just two secondary market platforms (SharesPost and Second Market) in 2011. And Facebook has been extremely active. In 2008, for instance, the Securities and Exchange Commission gave the company an exemption from a rule that a company could only trade 500 shares of its private stock, with the caveat that most of the shares had to remain inside Facebook.

But to buy a share on the secondary market, you need to be an “accredited investor” – i.e., have a net worth more than $1 million and annual income exceeding $200,000 ($300,000 if married.) Also, Facebook shut down trading of secondary market shares in late March in advance of the IPO. Road closed for me.

Background reading on grabbing shares released in the actual IPO did not suggest hope for a financial peon like myself. The conventional wisdom is that buying IPO shares of a hot company involves being cozy with the firms that help structure the IPO deal — the underwriters. Those underwriters, big investment firms like J.P. Morgan-Stanley-Chase-Bear-Stearns-Goldman-Sachs, figure out things like the initial price of the share and which firms get how much stock to offer to their (typically hyper-rich) investors. They also present the “roadshow” — face-to-face meetings with their clients where they make the case for acquiring Facebook stock. (The roadshow, complete with a video featuring Zuck’s toned arms and oddly made-up face, can be seen here.)

Facebook chose Morgan Stanley to lead the underwriting charge. Maybe Morgan Stanley would help me find a share?

I called a branch office and got transferred to a nice man, who paused at my request to buy a share of Facebook. This, after all, was awkward for him: I sounded like a lunatic. But he very sweetly told me that my chances as a poor neophyte who was not a financial juggernaut were nil. “To be honest, getting someone involved is difficult, let alone a new customer,” he said, “Retail investors just don’t get as many shares allotted.” His recommendation for his actual clients is that they find shares after they hit the open market.

Some hope arrived with stories that Facebook is trying to get some stock into the hands of “retail investors.” According to the New York Times:

On Thursday, Facebook added E*Trade as one of its 33 underwriters — an indication that the company could seek to bolster its retail allotment — but it did not indicate how many shares the online brokerage firm will get.

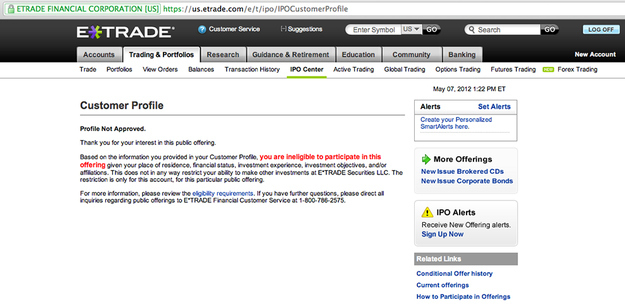

So I logged onto E*Trade and began to chat with a representative. She was not forthcoming but pointed me to a detailed FAQ about how to participate in offerings: I’d have to open an account and put money in it five days before the IPO goes public. I opened said account and began filling out the questionnaire, answering a slew of questions about whether I was related to any broker-dealers and about my trading goals and net worth.

Then, right when I was expected to get some “thanks for filling out the form” splash screen — BOOM — came the bad news: I'm ineligible to participate “given [my] place of residence, financial status, investment experience, investment objectives, and/or affiliations.”

I was perhaps too honest about my investment experience (none) and financial status (pitiful.)

There was one last avenue to investigate, one that takes me back to my stock-trading youth. As an investor with Fidelity, my dad sometimes gets chances to purchase IPO shares at IPO-offering prices. He’ll get an email with notification that X number of shares are available, along with a link to the company’s prospectus. He has to click on it as “a show of interest.” Then, he’ll get another email, usually the night before the IPO, saying that the short window is open to declare his intention to snag IPO shares. He has not gotten such an email yet for Facebook but he could in the coming days.

“Great!” I exclaimed. “Let’s do this!”

“Hmmmm,” he said, “Do you think it’s a good investment?”

Huh. In this whole process, that was a question I had never put to an expert, let alone myself. Is Facebook a good investment? Is it a company that you want to put your hard-won money into? In my father’s case, that would be my parents’ retirement savings. More abstractly but also importantly, is it a company that you want to support and help grow? That is, after all, what investing in something means. My justification for wanting Facebook — bragging rights? — seemed embarrassingly slim.

But still, the zeitgeist called. A Google bus rolled by my window.

“I have no idea,” I said, “But if you get some shares, can I have one?”